What kind of copyright subsists in a generative art NFT?

So now we know what elements are required for copyright to exist in the first place.

Assuming it does, what layers of copyright exist in a generative art NFT?

Broadly speaking, we are likely looking at 2 types of copyright:

- the artwork; and

- the code.

Assuming the code passes the copyright test above (i.e. a tangible and original work by a qualifying person), then the code itself that generates the artwork will likely have copyright.

But what about the artwork itself?

Well, that’s where things get tricky.

So artwork in generative art has no copyright?

Firstly, we can probably break “artwork” down into two parts (i.e. two separate, unique copyright with their own corresponding commercialisation rights/rights of use):

- the individual “traits”/attributes

- the final artwork generated.

Traits

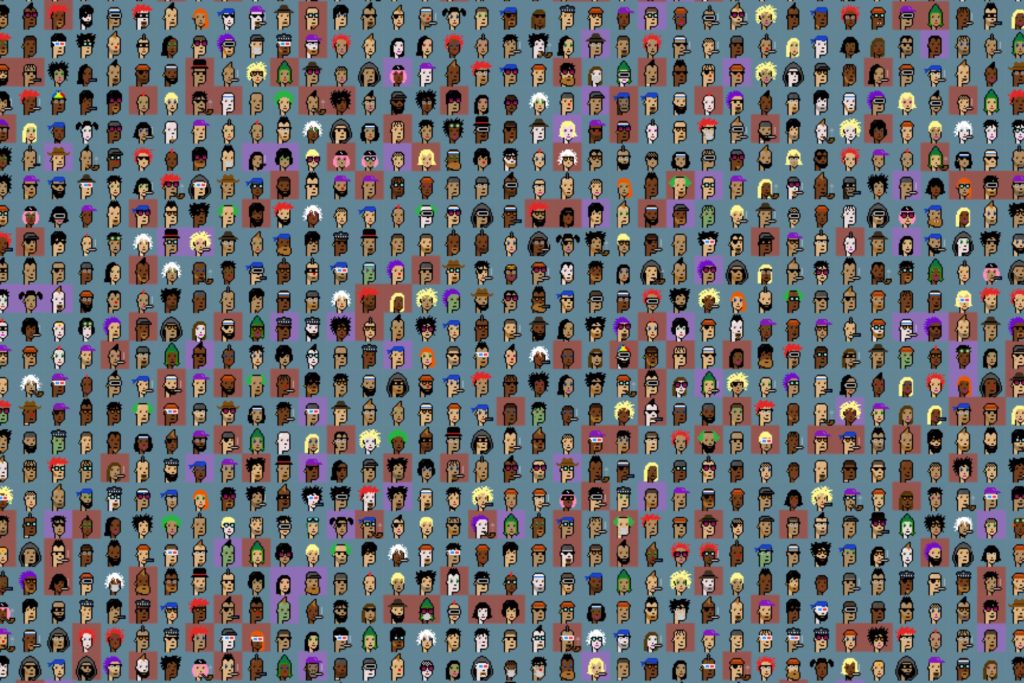

Let’s take Cryptopunks as an example.

Cryptopunks is an NFT project consisting of 10,000 uniquely generated characters. None are alike, but all of them have unique attributes that carry different levels of rarity, e.g. having a beanie, choker, pilot helmet, tiara, orange side, buck teeth, welding goggles etc (complete list of Cryptopunks attributes).

Each of these traits or attributes would’ve been created by an artist (or artists) with the assistance of computer programs. This makes it a computer-assisted work.

If you’re in a jurisdiction where computer-assisted artistic works are protected, then each of these traits might be protected. I.e. the rainbow beanie itself has its own copyright, the choker has its own copyright etc.

Why do I say “might”?

Because each of these attributes must pass the originality test (see above). You need to show that skill, labour and judgement was involved in the creation of the work. The question of to what extent is up for debate.

Here are some of the thoughts that’d be running through my head:

- If the trait took less than 1 minute to create, is that sufficient?

- If it’s creating spots, where you’re just adding on 8 grey dots to a Cryptopunk’s features, is there sufficient labour and skill involved?

- What about a red mohawk, where it’s essentially just a very small triangle?

- Or a clown nose, which is just one red dot?

- Et cetera et cetera et cetera (you can see how this discussion could be never ending)

My personal gut feeling is that it would be hard to argue that the individual traits have copyright in and of themselves in these instances.

But if the trait/attribute of another NFT project required a fair amount of skill, labour and judgement to create, then it might have a stronger case.

Final Artwork

Then we come to the final artwork, where all the “traits” come together.

Let’s assume these traits come together to form an entire artwork like a Crytopunk or a Bored Ape.

Like the Cryptopunks above, no 2 Cryptopunks are identical.

But are they really all that different?

Assuming that autonomously computer generated artwork can avail itself of copyright protection, then each Cryptopunk would likely have its own separate copyright protection as a derivative work.