Powered by RedCircle

Listen at: Spotify | Apple Podcast | YouTube | Stitcher | RadioPublic

Welcome to Episode 101!

Welcome to STIMY’s landmark 101 episode!!

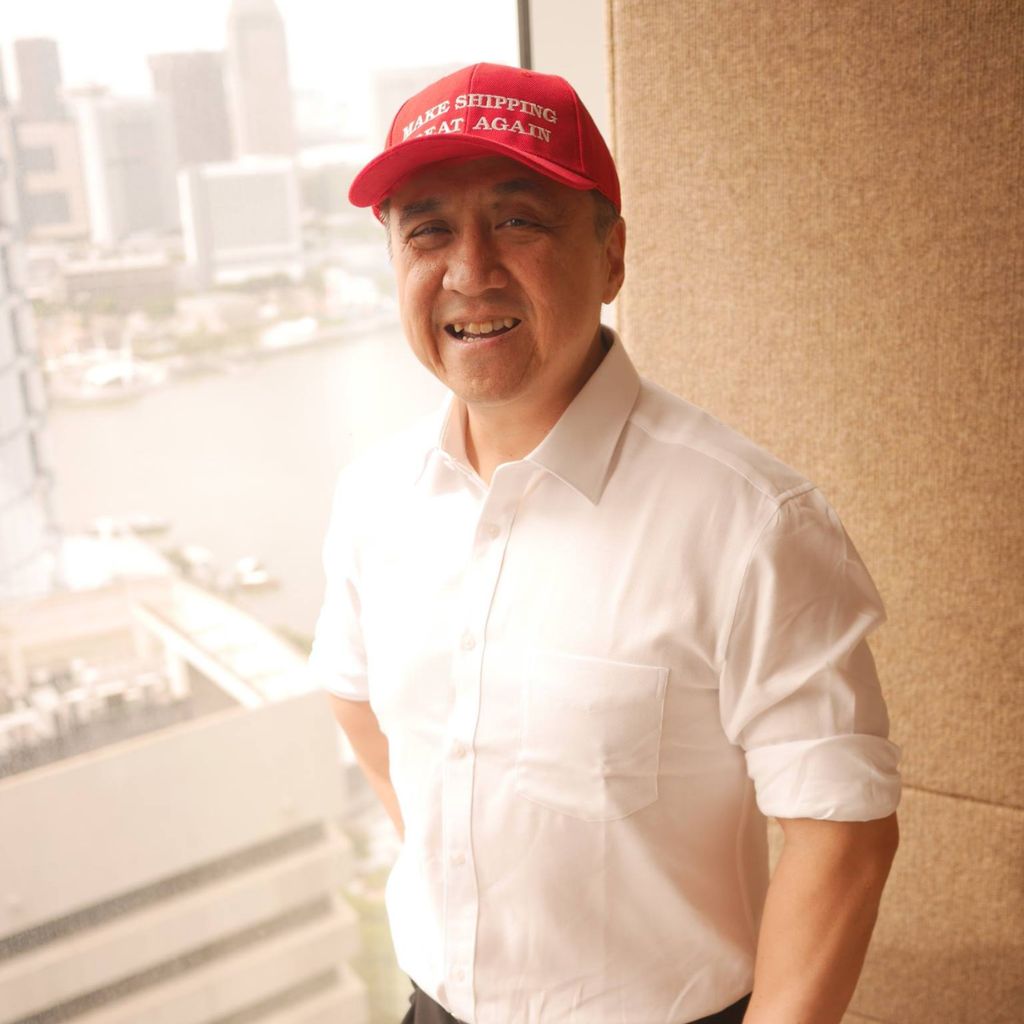

In this episode, we meet the King of Singapore: Adrian Tan.

Adrian Tan is a litigator specialising in technology, intellectual property, collective sales and shareholder disputes. He is the President of the Law Society of Singapore.

Adrian was the former general counsel of CrimsonLogic and holds a degree in computer science and psychology gives him the foundation to address technology-related disputes. His degree in computer science and psychology gives him the foundation to address technology-related disputes. He has represented clients in a wide range of technology and intellectual property disputes, ranging from data centre construction, social media defamation, copyright infringement and passing-off in relation to consumer electronics, and patent infringement of vaccines.

In addition, Adrian is also:

👉🏻 The bestselling author of The Teenage Textbook & The Teenage Workbook, which were turned into a play, movie and TV series etc.; and

👉🏻 LinkedIn writing extraordinaire (all his posts go viral & even hit the mainstream media headlines!)

But who is Adrian Tan, really?

How did Adrian Tan end up where he is?

What was it like growing up in a HDB community that didn’t understand the concept of “privacy”?

E.g. Everyone treated Adrian’s family TV as their own, and crowded outside to watch together. 🤣

How did he end up writing bestselling fiction novels (whose royalties put him through university)?

Why is he the King of Singapore?

And how has cancer ☹️ impacted him?

🔥 So much to cover in STIMY’s spanking new Episode 101.

You’ll just have to listen to find out more! 😏

P/S: Adrian’s episode is divided into 2 parts, with a special edition Questions from the Audience (where YOU, STIMY Listeners, submit your questions & STIMY guests answer them!).

PS:

Want to learn about more inspirational figures/initiatives to become the most interesting person in the room?

Don’t miss the next post by signing up for STIMY’s weekly newsletter below!

Part 1: Who is Adrian Tan?

Adrian Tan shares his origin story, how his parents got him into one of Singapore’s most prestigious schools and how he ended up writing two bestselling novels – the royalties were enough to pay for his university education!!

- 2:23 Singapore’s immigrant story

- 10:33 Getting into Anglo Chinese Primary School through ballot

- 15:54 Maternal gaslighting

- 19:20 The TV belongs to everyone! 😫

- 21:59 Top grades doesn’t guarantee success in life

- 24:59 Chinese people can be very racist

- 30:02 Failing to get a scholarship to study law because Adrian’s English was too good

- 33:10 Why law?

- 34:31 Writing for magazines & getting a book offer

- 36:31 Getting a book deal to write The Teenage Textbook & The Teenage Workbook

- 38:38 How much royalties do authors get?

- 40:56 Why did a subversive book become a bestseller?

Part 2: Becoming President of Singapore’s Law Society, LinkedIn & Cancer

Powered by RedCircle

In Part 2, Adrian Tan is BACK to share how his career developed as a lawyer, why he hated his time as a General Counsel, thinks that lawyers should be legal influencers, how his LinkedIn posts go so viral and more.

Highlights:

- 1:58 Embarrassed by his bestselling books

- 5:59 The non-confrontational litigator?

- 10:01 Working with Davinder Singh, one of Singapore’s top litigators

- 12:50 How to be a good legal associate

- 14:16 The art of persuasion

- 15:28 Secret to good writing

- 17:25 Becoming the General Counsel of Crimson Logic

- 20:18 It was awful

- 21:26 Being involved in the Singapore Law Society

- 24:05 Lawyers need to be legal influencers

- 26:55 Writing bland posts to…?

- 32:10 Advice for young lawyers writing online

- 33:20 The secret to viral posts

- 34:48 Fighting cancer, cases & for lawyers

- 37:41 The 3 friends we have

Part 3: Questions from the Audience for the King

Powered by RedCircle

Several weeks ago, I asked if anyone wanted to speak to the King of Singapore aka Adrian Tan.

Turns out, 5 of you did!

And the King has answered them all.

A special Questions from the Audience episode has just been released on So This Is My Why Podcast.

We dealt with vital national security issues like… how Malaysia’s food is wayyyy better than Singapore 🤤.

Ok I jest.

Or maybe not. 😝

Regardless, the special Episode 101.3 is now OUT!

And here are the highlights:

- 1:01 Cancer treatment & mortality

- 2:04 How cancer affected Adrian’s work performance

- 3:43 Adrian’s many, many, many hats!

- 4:00 The tipping point that changed Adrian’s perspective on serving others

- 5:46 Advice for a son who wants to become a lawyer! 🤩

- 7:29 What keeps Adrian motivated even after being diagnosed with cancer

- 8:57 Singapore’s death penalty on drug trafficking

- 11:19 What’s behind Singapore/Malaysia’s cultural divide?

Special Thanks

To Aaron Lim JC, Jeff Ong, Kris Ang, Jade Tan and Dave Nathar for submitting your questions & being part of STIMY!

P/S: Links to this episode can be found in the pinned comment below.

Some of the inspirational past STIMY guests we talked about:

- The Woke Salaryman: Singapore’s most popular personal finance comic-drawing duo

- Davy Liu: Former Disney animator who’s worked on The Lion King, Aladdin, Beauty & the Beast, Mulan, Atlantis & Star Wars

- Eric Toda: Global Head of Social Marketing & Head of Meta Prosper, Meta

If you enjoyed this episode, you can:

Leave a Review

If you enjoy listening to the podcast, we’d love for you to leave a review on iTunes / Apple Podcasts. The link works even if you aren’t on an iPhone. 😉

Patreon

If you’d like to support STIMY as a patron, you can visit STIMY’s Patreon page here.

External Links

Some of the things we talked about in this STIMY Episode can be found below:

- Adrian Tan: LinkedIn

- Subscribe to the STIMY Podcast for alerts on future episodes at Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Stitcher & RadioPublic

- Leave a review on what you thought of this episode HERE or the comment section of this post below

- Want to be a part of our exclusive private Facebook group & chat with our previous STIMY episode guests? CLICK HERE.

Ep 101.1: The King of Singapore | Adrian Tan [President of Singapore's Law Society]

===

Adrian Tan: Why am I here? What am I supposed to do? For me, it was easy to answer that question.

I'm supposed to be here to talk. To speak up for other people as a lawyer or as something else. I'm supposed to be an advocate.

I know this because I like doing it even when I was in school. I always wanna speak. I always wanna speak to explain what was going on and to put across a point of view.

So to me, being a lawyer was the ideal job. I had no idea what a lawyer really did. Who among us really know?

It was that romantic idea of, yes, I'm going to fight for justice. I'm gonna stand up for the weak. I'm going to be the voice of the oppressed. I will be a lawyer. Honestly, there was nothing else I could see myself doing.

Ling Yah: Hey everyone. Welcome to episode 101 of the So This Is My Why podcast.

I'm Ling Yah, back as your resident host and producer. And this week, quite apt given the political turmoil that Malaysia is going through, we are meeting the King of Singapore, Adrian Tan.

Author of two bestselling books, the Teenage Textbook and The Teenage Workbook, which has turned into a play movie and TV series. The President of Singapore's Law Society, a partner at TSMP and also LinkedIn writing extraordinaire. His post go viral and sometimes even hit the mainstream media headlines.

But who is Adrian Tan, really? How did Adrian end up where he is?

What was it like growing up in a CBD community that didn't understand the concept of privacy? How did he go from writing fiction to becoming the top of his legal field and just why is he the king of Singapore? All that and more in this episode, which is divided into three parts.

The second part will be released this coming Sunday, and the third will be released thereafter, Which will feature a special questions from the audience episode because some of you had questions for Adrian and he's given his answer.

So are you ready to hear part one of Adrian's story?

Let's go.

Adrian Tan: The story of Singapore is always a story about immigration.

There are people who are many generations here, but the vast majority of people in Singapore and Malaysia, are immigrants and each person has an immigrant story.

So my immigrant story is about a cook. My grandfather was from Hainan Island and that's the Hawaii of China. Why is it the Hawaii of China? It's an island. It's very sunny. They're great beaches and in fact it's a great place to go on a holiday. But for his own reasons, he didn't want to stay there.

So he took a boat and came over to Singapore.

And when you look at the waves of immigration for the Chinese that came to Singapore, I think the Hokkiens, the Cantonese, the Teochews, they came over first. They established businesses. And when the Hainanese came over right at the end, we had only two occupations.

One was F&B and the other was and I read this somewhere, it's very surprising. The other was male prostitution. So male prostitution goes like this. When the British set up Singapore, they didn't want too many women migrants. So they focused on male migrants. That's because they thought that men would be able to do construction work and build a new city and so on.

Because there was a shortage of women, I think some of the men or some of the boys turned to male prostitution. I'm not sure how voluntary it was. I'm sure a lot of it was coerced or worse. But this thesis I read in university said that a lot of heese because they came right at the end, the young boys ended up being male prostitutes.

I dunno how true it is, but it was said to be like this because Hainanese boys were very attractive.

But the point is that when you ask most Hainanese what did they do when they came here, most Chinese ancestors will say they were in the F&B industry because they don't wanna say anything else.

So my grandfather was like that. I don't know a lot about him. He was a cook in some Englishman's house.

When my father was 10, his father, my grandfather, met with a traffic accident and he died. My father was really upset because he said that the boss, the Englishman didn't even provide money for the funeral. That death had a lot of impact on my father because at that time, Singapore was still occupied by the British.

There was only one route of advancement, then as now. It's education.

My father was really bright, but because of the death of his father. My dad couldn't go on with further studies.

He ended up being a teacher and that's a source of, I would say, discontent for him. Cuz he was very, very bright and he could have been destined for great things if his father hadn't died.

So this is the sort of life changing event that happens not only to one generation, but generations that go down. You see, if they're successful migrant families, it's sometimes not because the migrants himself was very astute or very capable. It's simply because he didn't die. He just managed to survive and raise a family and provide for them.

And with that, a new generation is born. I think today when we look at migration, whether in Singapore or elsewhere, we also have to think, what sort of migrant are we getting?

What are their stories?

I often wonder and compare their stories to mine. Are we going to get more generations of Singaporeans who can contribute?

And what type of migrants will we have? I'm not sure if I can say the same in Malaysia. I don't know enough about Malaysia, but I suppose there's some level of immigration as well.

Ling Yah: When you were talking about that, it makes me think of some of the posts that you've written.

It sounds like as though you were very much more open-minded than some people about the idea of immigration, for instance, that's one topic you wrote about.

Oh, foreign workers, should they have access to free legal advice. Don't they need to have that kind of proper representation? Do you feel you being aware of your original story allowed you to be more empathetic?

Adrian Tan: Well partly. But let's face it, they are human beings.

Because they are not from the same country and so on, we should give them different rights.

I feel that Singapore itself is built on migration. It's a city that was created out of nothing. The British came and they founded it.

Before that it was a trading port. Very successful. But the British were the ones that introduced large scale migration and they completely changed the culture.

When we have a lot of migrants who come here, and they establish a new city. Within a few generations we have a national anthem.

We are republic. We have our own way of talking. We have our own food, our own jokes. Suddenly, Singaporeans start feeling that they aren't migrants anymore, which is fair. They're not. I'm not. I'm not a migrant at all. But then they start thinking, I want Singapore to be frozen like this forever. I don't want change.

I don't want people to come in from outside and start changing the Singapore that I love. Maybe the people that come in are from Europe or from America, from India, from China. It doesn't matter.

They're different from me. Now that I'm like this, I wanna put Singapore in a jar and not change it.

I feel that I can understand why people feel that way. Singapore is a nice place, but I think it's not realistic and it may actually be better for us if we accept migration is necessary. Especially when our, our country is not growing.

Now, one interesting thing is that the number one source of migrants that Singapore seems to want is Malaysia.

Ling Yah: Malaysia wants you back too.

Adrian Tan: Yeah, I think Malaysia wants Singapore back in a way. But Singapore also wants to capture, attract, maybe that's a better word, the best that Malaysia can offer.

I'm not even sure there's a source of tension, but there is some thinking that, when you look at Malaysia, they're very, very much like Singapore.

Malaysians, they look like us. They talk like us. They eat more or less the same thing, and they have the same values. The same outlook.

And so it's very easy for Malaysians to assimilate.

When Singapores think , Okay, Singapore is not growing, we need to grow it. But where are we gonna get people from? Are we gonna get people from America?

No, we don't like that. Australia, New Zealand? No. Europe, no. China, India, no. They're still very different from us. Hmm. Oh, Malaysia. That's just like Singapore.

So during Covid when we were having a lockdown, and immediately after there was a spike in work and business. Everything just spiked up once the lockdown ended and people started looking for new employees and immediately people started thinking, Oh, maybe we should look to Malaysia.

Maybe we should find some way to attract Malaysian lawyers, Malaysian doctors. Malaysian anything to come over here and then we'll start that story all over again. I'm not sure how Malaysia feels about that though.

Ling Yah: I think Malaysians, a lot would jump at the chance to go to Singapore and three times what you're earning here as well.

So ...

Adrian Tan: Well, it costs three times more and I have to say that culturally there are many similarities, but also, yeah, a lot of differences.

So I think that Malaysians can be very outspoken when it comes to politics and other areas.

We kind of want it to be a bit more exciting than what it is already because it's so predictable what's gonna happen. The same people's action party will go back into power because they very popular.

They'll always have a mandate. They'll form their government. Maybe the opposition will win a few more seats, maybe not. And that's the drama for the day.

Then the next day everybody goes back to work. And when we look across to Malaysia, we think oh look, it's very different.

There is all kinds of activity. So I think that's the comparison that sometimes Singapore has with Malaysia.

Ling Yah: I suppose it's always the case of grass is greener on the other side.

I wanted to go back to the theme of acceptance and what your father went through. I imagine that even though you might not have been fully consciously aware of his discontent, he must have filtered down through the way that he lived his life, your family life as well.

And I read that you actually got into this really elite primary school, Anglo Chinese primary school. What was the story behind that? Because that was something that really transformed your life, right?

Adrian Tan: So my father was a primary school teacher and so was my mother. In fact, that's where they met. And I was their first child.

I have a brother. My parents both believed in one thing, the power of education to transform lives.

When you think about Asian immigrants or Chinese Singaporeans or any kind of Singaporeans, honestly, they are big believers in education. Now, if you get into a time machine and go back to the 1960s, that was when I was born and you see the Singapore that existed then.

It was a very new country. There were some small industries that were just starting out. By and large people had no idea what Singapore would be like.

For people like my parents, they had no money. They weren't going to start a business or hand anything down to me to say, Oh, here is a big piece of land. Here is a house. Here's a factory.

The only thing they could pass down to me was education. Education is something they could give me and I could take wherever I went. And in the mindset of the Singaporeans in the sixties and seventies and eighties, the one thing they were always talking about was migration. So they were migrants.

They talk about migration. What do you mean they talk about migration? Well, in the sixties, seventies and eighties, you'll get Singaporeans sitting around saying, Oh, my dream is to migrate to Australia. My dream is to migrate to Canada. My dream is to migrate to the United States. Wouldn't it be nice to live forever in London?

And you think, real strange. Why you thinking like this? Oh, because we don't think that Singapore's gonna be around that long.

I mean, if you knew how Singapore is formed in the sixties and seventies, we had all kinds of issues. We were still a very new nation. And so a lot of people had this backup plan, which is that if I had the chance, if anything happens to Singapore, we are leaving. We're packing our bags, and we're going.

Now, you must remember, in seventies, that was the Vietnam War where there was a danger.

Ling Yah: Communism.

Adrian Tan: That's right. Communism would happen and there would be a domino effect. The communist would come down Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore.

Even in the jungles of Malaysia, there was the Malayan Communist party.

There was lots of stuff happening. So it's understandable that Singaporeans of that era always had their backup plans. And the backup plan works if you have either got money or education.

So since we didn't have money, my parents thought, Okay, best bet is to do education. But their idea was really different because they thought, let's send our child to a school full of elite people of the very rich and privileged people.

That's because we want him to go to a good school. And it was a good school, The Anglo Chinese School. I think that's one in Penang as well because everything that Singapore has, Malaysia must have.

No, seriously though there is an Anglo Chinese school in Malaysia. The one in Singapore is known to be a very good school, but also known to be a place where the children are from very privileged families.

My mother was determined to get me into that. It was not easy. In fact, you can't get in if you don't have a relative there. If you're not a member of the Methodist church or if you haven't donated stuff like that. They reserve a few places right at the end for people who have no connection with the school and those places are balloted.

So my mom and my dad stayed all night and then they balloted and I got in. And to me that was better than winning any lottery. Any amount of money.

At that time I was just a very ignorant child. My mom came back and she was so happy. I remember it was very late. I was wondering where my parents were and she came up the stairs of the flat. And then she just hugged me and said, Oh Adrian, we got in.

And I'm like, I have no idea what you're talking about. Then we went to buy a school uniform and she got a little bag for me. In those days, the school bag looked like one of those luggage bags that you go on a plane trip with. You know, you get a Samsonite bag with a little handle on top, no wheels.

So just miniaturized that. That was a school bag. I'm not sure why.

Ling Yah: It sounds like the Japanese school bag.

Adrian Tan: Yeah, I'm not familiar. I kind of think you're right. It's a hard case and it's got two little locks in the front and a little handle.

Ling Yah: Almost like a soldier's bag.

That's how they ended up today.

Adrian Tan: Yes, yes, that's right. That was the thing. That was all the rage. Everybody had that kind of bag. Nobody had a knap sack. Nobody had any other kind of bag. That was the standard bag.

I think mine was $15 or something. It was pretty expensive.

Ling Yah: Japan is selling it for a thousand dollars now.

Adrian Tan: Okay, well there you go. I should have kept mine. I'll be rich now. Duh. Should have spoken to you earlier.

So my parents put me there. The first day I went in my new uniform and my bag, to my shock everybody there spoke English. And to me, growing up where I grew up in Commonwealth Close, which is a public housing estate, the kids all spoke to each other in Hainanese or Chinese, or a mix of Hokkien. It wasn't English for sure.

It wasn't even good English. That's definite. But in ACS, everyone spoke good English. They spoke grammatical English, so naturally and so fluently. So I went back and told my mom. I said, look, everyone there speaks English. And she said, Yep that's fine. You have to be the best at English because I'm an English teacher, so if you're not the best, it would be a huge disgrace to me and it would make me very embarrassed and everyone say bad things about me and you wouldn't want that, right?

If you burden a seven year old child with all that kind of guilt...

Ling Yah: maternal gaslighting .

Adrian Tan: That's right. Maternal gas lighting. I had no choice. My mom also phrased it this way. She said, Look, you are the son of two primary school teachers. We actually teach English, maths and science every day and we've been doing it for years.

So we are really good at that. We are gonna teach you and you'll be really good at it. If you look at all the kids in class, their parents are not primary school teachers. This person's parent may be some entrepreneur. That person's parent may be some doctor, some lawyer, some government minister.

You should pity them because they don't have good parents who can teach them. I kind of got suckered into that mindset. I wasn't in a condition to resist anyway.

My mother was a very strict teacher. And when I say very strict, you know what Asian parents can be like. She had a ruler, she had a feather duster.

Ling Yah: Anything she can get her hands on.

Adrian Tan: That's right. That's right. There was a lot of running around the flat, let me tell you that. I think she made me think that I had to excel and had to be better. If I didn't, I'll be letting her down.

There were all kinds of pressures.

Today when I talk to parents, I'm not a parent, they say, Look, we don't punish our kid. We don't do anything to make our child feel bad.

We are very gentle. I can understand it. I'm not able to tell people how to be parents because I'm not. But I wonder whether the old way was more effective. It probably left me with a lot of emotional scars.

But you know, for Asians, what's a few emotional scars, right?

What my brother and I thought when we were adolescents and teenagers is the same as practically every teenager in the world, which is we know everything.

We're really smart and our parents are not cool. They don't get stuff. We have a lot of issues. When I was a teenager, I had a lot of issues and stuff that I wanted to do. So I think my mother wasn't on board with a lot of it.

So naturally I thought that she needed to get with the program or she was not cool enough, not smart enough.

The thing I learned as I got older is my mother became smarter. I am now in my fifties. When my mother was raising me, she was in her thirties and she was just a young woman. She had a job and she also had to raise kids with my dad. They were both just trying to get by in this world. Didn't have much help.

They weren't from wealthy backgrounds, so they were just trying to make sense of a very rapidly changing role.

When my mom grew up, she lived in a compound that had a well. No running water, no electricity. Same with my dad. They would reared chickens and pigs and the sort of thing that you would have in a kampung.

Then she moved from that one generation to being in a flat with a telephone, with a television.

Ling Yah: Weren't you the first on your floor to get television when you were growing up?

Adrian Tan: We weren't the first, but we were among the first.

The thing about having a TV is that there would be people from other flats, from other homes that would come and watch TV with you through the window.

I used to do that before we had a tv. So if you live in a block of flats, you know pretty soon who has a TV and who has a telephone.

If you know that somebody has a telephone, most people who needed to make a phone call would go to that person and say, can I use your phone?

And then they'll bring a small gift. A cake or something. And then when it's tv, TV's different. TV was a communal event. So imagine if you are living in a tiny three room flat. We call it three room flat because it's got two bedrooms and one living room. That's a three room flat, about 800 square feet.

One bathroom. The bedrooms are small. So everybody lived in the hall. The hall was sort of merged into the kitchen, and one end of the hall had windows that opened into the common corridor.

Beyond the common corridor was the entire life of the neighborhood. Everybody would be sitting outside, talking and putting their noses into other people's businesses.

It was a kampung that was high rise. So if you had a tv, people would watch your TV with you. And if you're watching you wouldn't position your tv in a way where the back was facing the window and people would think there's something wrong with you. Don't you want us to watch TV with you?

So all the neighbors would crowd around the corridor and poke their heads through the window and laugh along or exclaim or talk, because Asian people, when they watch something, they have to talk and comment.

And so this is what's happening. Let's say you're having dinner in your home and you're watching TV and behind you, there's all your neighbors saying, Oh, why did he do this? Oh, this is very sad. Oh, I don't like this part of the show.

And you just like, Hello, I'm having food with my family. No, there's no idea of privacy in an HDB flat. So from a kampung, they moved to an HDB flat.

From there they have all these social morays, new ways of being a community that were developing. And so my mom was trying to cope with that. My dad was trying to cope with that.

They were just married and they have their married people issues.

And then there's me. And I'm thinking they're not cool enough. So my mom is probably thinking, I don't care if I'm cool enough. I'm still your mom. You're gonna do all this and so be it.

As I got older, I realized that she had a lot on her plate and so did my dad. I mean, in their thirties to deal with all that in, in their forties.

I was a really dumb ass I wasn't very smart.

Ling Yah: But you got top in your class most of the time.

Adrian Tan: But I'm talking about being ignorant about life. Having top results in school work is no guide to whether you'll succeed in life. Getting great marks in school means just one thing. That you are able to get great marks in school.

Doing well in maths doesn't mean that you'll be a great manager. So I'm always telling people, let's not overemphasize school results. It's no indicator of success.

Anyway in my thirties, I'm pretty sure I wasn't able to have a family, I mean, have kids and all that and, and raise them as well as my mum.

So as I got older, I began reevaluating my mum. I think we all do that in a way. We keep seeing our parents through different lenses in childhood and adolescents. As a young adult.

As we get older, and then now my mom's passed away, I think there's another lens. How unfortunate that I didn't have this lens 40 years ago, 30 years ago.

I could have said, mom you did a great job. All I remember was complaining about how she raised me.

Ling Yah: I suppose that's the reality that pretty much all of us are guilty of as well. We just don't have that perspective. Hopefully it's not too late when we do have.

I wanna talk a bit about Commonwealth Close, cuz it's such a fascinating world. The fact that you have no privacy whatsoever. Your business is everyone's business.

I imagine it wasn't just your floor. The whole block. You were in ACS and you're probably one of the only few ones there. Was there some kind of tension?

Adrian Tan: No, it wasn't a very competitive block for some reason. We were on the 11th floor, it was mostly Hainanese and we kind of stuck together a lot.

We'll argue among ourselves, but we'll still stick together. And we would know the business of each person whose family was doing well. Who got a promotion, which couple was having marital strife. Which child did well, which child did badly. Who is sick, who is not sick. They would take care of each other.

For example if someone needs to go somewhere, someone else would babysit. They would share food. When I say that, I realize how weird it sounds to me now. To the Singapore of 2022. But when I was growing up, people would cook and they would cook more than what their family would eat.

And then they would take a dish down to so and so the old lady, the washer woman, and say, Oh, you know, we cook the extra dish.

Or today is my kid's birthday. So we, we made a cake and they would also gamble together. That was a big thing. It's either taunting or something else called 'chap ji kee', which is some probably very illegal thing.

So the idea is that you would know every family from one end of the floor to another. There were good and bad things. Because everyone was the same dialect group I didn't know a lot of Malays, Indians and Eurasians until I went to ACS, which is why it was so eye-opening. But I didn't know how to relate to them.

And when you're young, Chinese people can be very racist. I don't know whether you realized this, but Yeah. When you're young,

Ling Yah: You're very racist and you don't accept that you are racist.

Adrian Tan: That's right. That's right. My neighbors would say, If you don't behave, the Bengali man will come and put you in a sack and take you away.

This is sort of thing they tell little children. So of course I had this paralyzing fear of Indians until I went to ACS.

And then I realized that, oh, these all my friends. I don't understand why my neighbors have been telling me all this crap.

Ling Yah: I imagine knowing how you grew up, you really understood what community meant.

That was all you knew.

When you went to Hwa Chong, then you really felt that distance, because I imagine you grew up thinking, I am Chinese. I'm Hainanese, and then you go to Hwa Chong and think I'm not a real Chinese. It must have been jarring.

Adrian Tan: Well yes. You're quite right but what happened was that my first school eradicated a lot of chineseness from me.

My first school being ACS. My second school, Hwa Chong, tried to put a lot of it back, but there wasn't enough time.

It's hard to put Chineseness back into someone. So ACS is a place where we are known for many things. For example, swimming, sports being good at business, chatting up females. But we we're very bad in Chinese.

It's legendary in my time how awful ACS boys Chinese was. It was also taught very badly at that time. There was a lot of memorization.

Imagine the entire week you're speaking English. You listen to English music, you watch English movies and TV shows, read English books and then for just two hours that week, suddenly you have to speak Chinese and you have to be good at it.

I couldn't make the switch. I think it's a terrible way to teach a language.

Ling Yah: I agree.

I went to the same school. I mean, the difference was that I was in a primary Chinese school for six years, so I had that grounding, but then when I went to a private school where English was spoken the whole time, and so unless you spoke Chinese language, I could see the difference.

You don't learn Mandarin in that way for two hours a week.

Adrian Tan: Yeah. Absolutely, right? There must be a better way to do this. I was totally uninterested. I didn't think there was any point in me learning Chinese. There was no utility and it's not fun.

I associated it with pain and all kinds of horrible things.

Then I had a scholarship to go to Hwa Chong.

Hwa Chong is diametrically opposed to ACS in terms of Chineseness.

At one end of the scale you have ACS. Not just English speaking, but very westernized in their outlook in the way they deal with people. In the way they talk to their teachers.

It's all very casual and there's a lot of humor and jokingness. And then you go to Hwa Chong and it's on the other end of the scale.

It's quite formal. It's less individualistic, it's more group oriented, and it's very Chinese. I went there because the government said that they would pay me $2,000 a year if I switched.

I studied in this program called the Humanities Program in Hwa Chong. That was a program which had teachers from England come to Singapore to teach economics, geography and literature and history to Singaporean students.

This is an idea from Lee Kuan Yew. Lee Kuan Yew thought that Singaporean children needed to be taught English by native English speakers.

And so he got the best teachers from England to come over. And some genius in the Ministry of Education thought that the best place to put these very westernized English teachers was in the most Chinese school in Singapore.

So you go figure the mystery of government.

That's why I can't be in government.

So I had to go and I had to spend my time in inside this English capsule within Hwa Chong, this little world where 22 of our students would listen and interact with these native English speakers all the time. They'll teach us stuff about England. And then we step out of the classroom and we get provided with Chinese everything. So in Hwa Chong, the school song's in Chinese. When you play sports, you cheer in Chinese. The biggest festival in Hwa Chong was the Mid Autumn Festival or Moon Cake Festival.

I'm giving these examples to show how Chinese it was. Not very alien to me.

If I could travel back in time, I definitely make better use of my two years in Hwa Chong. But at that time, it was too much for my tiny mind to cope with having to learn English stuff and then having a Chinese world out there.

So I had to give one of them up. Now when I go back to Hwa Chong reunions, I feel very embarrassed because I'm nowhere near the ideal Hwa Chong student. Very far from it.

Ling Yah: I can sense that feeling because one of the first things that you read on your LinkedIn profile is, " speaks a form of Chinese not recognized or understood in China".

So clearly you still feel that very, very much. I thought what was really interesting as well, cuz you said, you talked about going back in time.

I imagine another thing you would wanna change is the way you conducted your scholarship because it was because of your good English that you didn't get a scholarship to do law.

What's the story behind that?

Adrian Tan: It's so frustrating and mystifying. The idea is that I had a small scholarship for the A Levels. That's 17 and 18 years old and that was to pay for my pre university education.

But the biggest scholarship was for university. Once you get your A level results you go for an interview and they will decide whether or not they will send you to England to do your university degree.

And who will interview you? Well, it's the government in Singapore. Everything's the government. So the government had this panel, this commission, and it was one of the most eye opening interviews of my life.

I remember going there and talking to the panel and it went quite well for a while.

Then the chap in the middle who was the oldest and who had a bit of an attitude, if I can say that. He had a bit of an attitude, said, Well what do you wanna study? I said, I wanna study law. I really like law. I wanna be a lawyer.

He says, Oh, oh, no, no, you can't. we are going to send you to England to study English to become an English teacher.

And I said, but I don't want that. I want to study law. And he says, Well, your English is too good for law. And I was, What? What are you saying?

He said, Well Lee Kuan Yew and you know, whenever they start a sentence with Lee Kuan Yew, you know, you can't rebut it.

He said to me, Lee Kuan Yew, our prime minister said that the standard of English among lawyers is very poor.

Now your English is good. Therefore, by pure logic, you cannot be a lawyer. Obviously I wasn't gonna stand for that. I said, No, no, no. I could raise the standard of English among lawyers and so on and so on.

But they were just not going to change their minds. So in the end, they offered me a scholarship to study English in the uk and then to become a teacher after that.

I did want to go to England and have a chance to have a four years of all expenses paid university education and get a degree and come back and have a job. But it wasn't the job I wanted.

It was the most awful decision of my life. But I think I'm quite sure I made the right decision because my life is a lot happier now as a lawyer.

So I had to tell my dad that they're not giving me a scholarship to do law. They're giving me a scholarship to do English. And he got very upset because he's very anti-system. He's a rebel.

Ling Yah: I can see where it's coming from now.

Adrian Tan: Oh dear. Oh dear. But yeah, to him this confirmed that the system was nuts.

He said, Well, alright, I'll pay for your university. By that time my dad and mom had already divorced, so it was nice of my dad to say that. So he said, Okay, I'll pay for your university in NUS, National University of Singapore and you can study law there. It's not really expensive to study university in Singapore.

The fees are quite affordable. I think they're still affordable. So because of that, I ended up being a lawyer. But NUS law faculty is a whole different story.

Ling Yah: Why law?

Because you wrote about it before saying if you did law, there's also no guaranteed job as compared to doing English.

Was to kill a mocking bird that inspiring that you really needed to be a lawyer?

Adrian Tan: I think in life we all have an identity and sometimes we can find it and sometimes we can't. And Ling Yah, you can call it your why.

Why am I here? What am I supposed to do? For me, it was easy to answer that question.

I'm supposed to be here to talk. To speak up for other people as a lawyer or as something else. I'm supposed to be an advocate.

I know this because I like doing it even when I was in school. I always wanna speak. I always wanna speak to explain what was going on and to put across a point of view.

So to me, being a lawyer was the ideal job. I had no idea what a lawyer really did. Who among us really know?

It was that romantic idea of, yes, I'm going to fight for justice. I'm gonna stand up for the weak. I'm going to be the voice of the oppressed. I will be a lawyer. Honestly, there was nothing else I could see myself doing.

I thought I might be a writer as well, but it seemed too much to do. Four years of university to learn to be a writer. I thought that maybe I could do both in university, in the law faculty.

Ling Yah: You did end up doing both actually. Before that during NS you wrote for two magazines, like Men and Hot and it was a Yuppi talk.

Adrian Tan: That's right.

Ling Yah: Personality. And then you wrote a book. What's the story behind that?

Adrian Tan: Yes. Yes. In Singapore men have to do two years or two and a half years of national service in my time. Our allowance was something like a hundred dollars a month.

It wasn't a lot so it was common for us to try and earn extra money.

One of the things that I tried was to be a tuition teacher to teach English.

Ling Yah: Clearly not for you.

Adrian Tan: Cause I was really bad. I was the worst in Singapore. So I thought like trying something else. I started writing and I met someone at a party who was in a magazine, and I offered to write. He offered to pay me 15 cents a word, which is a lot of money. .

Ling Yah: Even today.

Adrian Tan: Even today, is that right?

Ling Yah: Yes.

Adrian Tan: Yeah. So I write every month. I write these articles for him and he published on Lifestyle Magazine, and it's one of these very posh magazines about how you should holiday and what restaurants to go to.

The reader would be some young executive, maybe some middle management person. Definitely not me.

I would try to imagine what that life was like, and then write about it. I read other magazines: American magazines, British magazines, try and get a sense of, Oh, the reader is somebody like this.

Then I would translate that to Singapore and then produced the stuff every month. And every month I would be paid.

Then I was asked to do an advice column for Women's Magazine. The idea was that for most women's magazines, there are advice columns, but the person giving the advice is a woman. And she's usually talking about men problems with other women.

So my angle was, Well, if you have a problem with a man, then why don't you ask a man about it?

I can tell you more about our problems and you can see for yourself how problematic we are. So I did that column for a while. Eventually I met someone else at a party and he was a book publisher.

He said, Oh, I read your articles.

Ling Yah: That's Goh Ek Keng, right?

Adrian Tan: Goh Ek Keng. Yes. Okay. Goh Ek Keng is my publisher. He's also a lawyer. He's also from ACS. So it's kind of like a tiny little world that we live in.

He said, why don't you write a novel? And I said, Oh, oh, I've never tried that. Then I said, But maybe I'll write a science fiction novel, maybe, Rocket ships and whatnot.

And he said, No, no, you should just write about something you know. What do you know? And that was great advice, right? About something, you know. I said, The only thing I know is I've just finished junior college, pre university. That's the life that I can recall. And he said, Okay, you just write about that.

Then I said, But that's just about going to school and meeting girls and getting to trouble. He said, Yeah, yeah, but you know, that's all you know, right? So just write that.

So I wrote that. That was called the Teenage Textbook. It came out in 1988 during my first year of university. And it immediately became a best seller.

I'm not sure why. So if you're in Singapore in 1988, the world was very non Singaporean as far as books were concerned. If you went to a bookshop, you would see tons and tons of books from the west.

Very few Singaporean novels. You would probably just see five Singapore books, if anything. And so I had very little prospect of success.

I thought I'll write this and maybe three people will read it. I'll give one copy to my mom and that's that. But I think my publisher had something to do with it.

He got me good reviews. He talked to a lot of people and he argued with a lot of bookshops, to be honest, said, Oh, look, this is a new book. You must carry it and you must put it here. I'm gonna come and check up on you. I want you to sell a lot of copies of this book.

And so before long the book became a best seller. It became the biggest, best selling novel in Singapore. It was number one on the bestseller list for more than a year.

Ling Yah: You were loaded.

Adrian Tan: Well, okay, let me explain the economics of it. For an author, each book gets you 10% of the cover price in those days. Different people have different deals. I'm sure J K Rowling has a much better deal. Yes. And she deserves it.

But for me it was 10%. So the book was $7.75.

So every book that was sold, I got 75 cents. The royalties from my first book and my second book put me through University, and after that through Pupillage.

So I always like to say that I went through university either 15 cents a word at a time, or 75 cents at a time because every week I would check, how is my book selling?

Will I get enough money to pay for this and pay for that?

Ling Yah: Were the Royalty cheques coming a quarter of every year

Adrian Tan: Annually, but in the beginning it was quarterly. They sold tens of thousands of copies. It was astonishing. The book became a play, a movie, a TV series, comics, many other things.

And even to me, amazing licensing deals.

Yeah. Well, I should have thought of that, but,

Ling Yah: Oh, no, you didn't as an IP lawyer.

Adrian Tan: No, you're right. It's very embarrassing. Fine. But I gave away all for free.

Ling Yah: So that's the thing, right? I mean, because I've also been offered a book deal and the big question is always when you write, is it normal for the publisher to own your IP?

Because that's the most important thing.

Adrian Tan: No, no, no. You should own the copyright as the authour. And you should license your copyright to your publisher to do a few things. First, to publish the books. Second maybe to publish translations. Depends on you. And then you must have a clause that says if your book goes out of print but you're publisher doesn't wanna do reprints, then you have the right to do reprints.

Ling Yah: Yeah.

All the IP rights will revert to you.

Adrian Tan: Yes, that's right. So you must always own the copyright as a writer.

Ling Yah: Exactly. I wanted to say, when I was posting on LinkedIn saying that I was interviewing you, I immediately got a lot of responses and there were two people just to encourage you, he immediately went, I remember him for teenage textbook and teenage workbook.

Another person said, Enjoyed the book so much as teenager even got copies from my teenage children many years later.

So clearly, it still strikes a chord even amongst Singapore now.

What I thought was so fascinating about your novels is that it's a subversive book. It was basically showing students you follow textbook answers, things will always go wrong. It seems to fall in line the way that you write with what you have always been.

Like you said, I always argue against people, I always speak up. Were you always contrarian, where you always going against the rules? Is that just part of your nature?

Adrian Tan: Well, you're absolutely right, Ling Yah. It is a subversive book, and it's subversive because I'm not really a subversive, or at least not on the surface.

On the surface, I try and get along with people. But deep in my heart, I always go, Hmm, this is wrong. Why is it like this? I don't have the personality or the inclination to be confrontational with people. So it all comes out in my books and in my writing. So when people read what I write, they have a certain impression of me as being very outspoken and always always ready to point stuff out and having a strong opinion on stuff.

But then when they meet me, they are nonplus.

They feel, oh, this is not you at all.

In my book, I'm trying to capture that idea. The teenage textbook is a story about how young people meet and they fall in love or they have relationships, but with the help of a textbook. And this is very Singaporean concept.

The concept is that in Singapore you should be told and taught everything. That if you follow a manual for life, if you follow a textbook, you'll be able to succeed. Nothing will go wrong.

Ling Yah: And if Lee Kuan Yew says then there is definitely nothing wrong.

Adrian Tan: That's right. Exactly. And that may work for school work. But it doesn't work for life.

And so the teenage textbook is a textbook about life that the characters in the book use and whenever they refer to it and follow its instructions, everything goes wrong. Eventually they have to abandon using a textbook and muddle along through life like the rest of us.

Ling Yah: And that was the end of episode 101.

The show notes and transcript can be found at www.sothisismywhy.com/101 stick around for this Sunday though, because we'll be continuing Adrian's story, starting with why Adrian was ashamed by the success of his novels, even when those royalties did put him through university.

He also talks about what it was like working with Lavinder Singh -known as one of the top litigators in Singapore, what it's like being the president of Singapore Law Society. Why he thinks lawyers should be a lot more active and prominent on social platforms like LinkedIn. How he's coping with his cancer diagnosis and so much more.

So do stick around.

Subscribe to this podcast if you haven't done so already, and see you this Sunday.