Powered by RedCircle

Listen at: Spotify | Apple Podcast | YouTube | Stitcher | RadioPublic

Welcome to Episode 93!

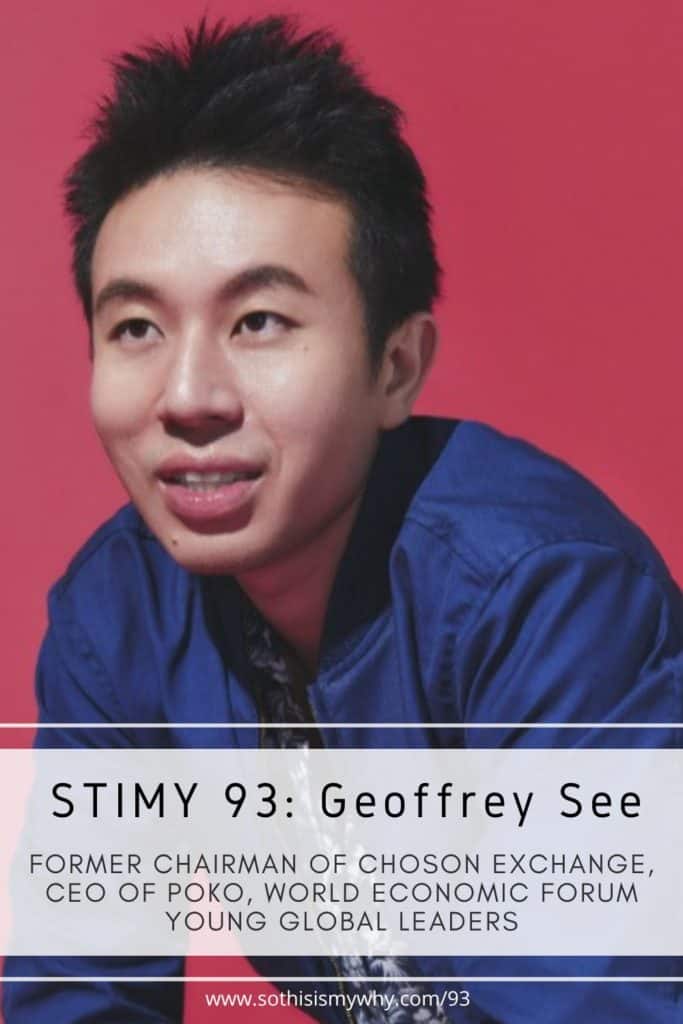

STIMY Episode 93 features Geoffrey See.

Geoffrey See is the former Chairman of Choson Exchange – the largest social enterprise teaching Western business skills in North Korea – and currently, the co-founder & CEO of Y-Combinator backed Poko.

He has also established a blockchain exchange that partially exited to Binance and helped launched blockchain protocol that at its peak had $2B coin cap.

Geoffrey is also a Digital Currency taskforce member and consumer protection report author at the World Economic Forum Global Council for Digital Currency Governance and and an Ethereum Foundation Fellow.

Additionally, Geoffrey is a World Economic Forum Council member, a Kauffman Fellow – a leadership program for venture capitalists. At Bain & Co., he worked on projects in private equity, technology, retail and consumer products.

PS:

Want to learn about more inspirational figures/interesting things I’ve found online that can’t fit into the STIMY podcast?

I share it all in STIMY’s weekly newsletter, which you can subscribe to below!

Who is Geoffrey See?

Here’s a quick run down 👇🏻

- Graduated from Yale University & the Wharton Business School;

- Worked as a Bain consultant;

- Co-founded Choson Exchange: a social enterprise that created the largest training program for female entrepreneurs in North Korea – which ended up being profiled in a Harvard Business School case study;

- Helped launch a blockchain protocol that had a $2B coin cap at its cap;

- Is a digital currency taskforce member and consumer protection report author at the World Economic Forum Global Council for Digital Currency Governance;

- Is a Ethereum Foundation fellow and a Kauffman Fellow; and

- Is now the CEO of Poko: a Y-Combinator backed startup focused on building DAOs to empower the next generation of investors, entrepreneurs and creators

Given that Geoffrey has had such a varied career, this STIMY Episode 93 is split into 2 parts:

- Part 1: On his childhood and journey in building Choson Exchange

- Part 2: Building and leading Poko DAO

Highlights in Part 1:

- 3:22 A strange relationship with authority

- 5:28 Wharton Business School

- 8:15 First brush with North Korea

- 10:31 North Korean men in politics, women in business

- 11:17 What does “business” mean in North Korea?

- 14:51 Building partnerships with North Korean Universities

- 16:34 Overcoming paranoia

- 20:16 How to find champions

- 21:48 Doing due diligence on potential partners

- 23:48 What North Koreans thought of the “rule of law”

- 28:26 Choson Exchange’s financing model

- 30:06 Measuring impact

- 31:15 Keeping the faith

- 33:58 The people that helped Geoffrey the most (i.e. a former Foreign Minister, National Security Advisor to multiple South Korean Presidents & ex-Global Managing Director of McKinsey & Company)

- 37:05 Deciding to leave Choson Exchange

- 38:56 The difficulties of letting go

STIMY Ep 92 Part 2: Poko DAO

To learn about Geoffrey’s journey into the #web3 space👇🏻

Powered by RedCircle

Building Poko

What does it mean to be the underdogs? One of the economically marginalised? Unable to open a bank account, cash a cheque… all the things that most of us would take for granted?

Geoffrey See – WEF Young Global Leader & serial entrepreneur – knows this well, because of his extensive work as a social entrepreneur in North Korea via Choson Exchange.

But after 11 years, Geoffrey knew that it was time to move on.

And in this episode (Part 2), we cover Geoffrey’s journey into the Web3 space. Why his experiences working in North Korea and Vietnam opened his eyes to the potential of blockchain, what he’s aiming to achieve with his new Y Combinator-backed startup, Poko, and his collaboration with the Kazakhstan government to provide the legal wrapper that many DAOs need but struggle to implement.

Highlights:

- 3:46 Introduction to Web3

- 6:33 Being economically marginalised

- 10:05 Is the ethos behind blockchain flawed?

- 12:18 What are DAOs?

- 14:24 Investment DAOs versus a Traditional VC

- 15:39 Reward mechanism

- 18:19 Proposals

- 20:22 Hallmarks of a successful DAO

- 22:02 Working with the Kazakhstan government

- 27:20 Why pick the Astana International Financial Centre?

If you’re looking for more inspirational stories, check out:

- Lily Wu: 2-time 7-figure entrepreneur & co-founder of WOW Pixies, a female-focused venture DAO

- Eric Toda: Global Head of Social Marketing & Head of Meta Prosper, Meta

- Nicole Quinn: Celebrity Whisperer & General Partner at Lightspeed Venture Partners. Portfolio Companies include Goop, Haus (Lady Gaga), The Honest Company, and Lunchclub

- Phil Libin: Co-founder on Evernote & mmhmm on why startup success is worse than startup failure & why he thinks that the blockchain is bullish*t

😅🫣

If you enjoyed this episode, you can:

Leave a Review

If you enjoy listening to the podcast, we’d love for you to leave a review on iTunes / Apple Podcasts. The link works even if you aren’t on an iPhone. 😉

Patreon

If you’d like to support STIMY as a patron, you can visit STIMY’s Patreon page here.

External Links

- Geoffrey See: Twitter

- Poko DAO: Website, Twitter

- Subscribe to the STIMY Podcast for alerts on future episodes at Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Stitcher & RadioPublic

- Leave a review on what you thought of this episode HERE or the comment section of this post below

- Want to be a part of our exclusive private Facebook group & chat with our previous STIMY episode guests? CLICK HERE.

STIMY 93 Part 1: Geoffrey See [Co-Founder, Choson Exchange]

===

Geoffrey See: It is difficult on all fronts, right?

One is they are paranoid. They are always suspicious of any foreigner. I'm from Singapore. So the good thing is that, it's seen as a neutral country and it gave us a lot of credence in North Korea being from Singapore, being from Southeast Asia.

And we also bring that philosophy, Singapore is not the most ideological, at least on some of these things. We believe that you take approaches that work for the country in terms of developing the country and improving people's lives.

That said, they are paranoid. It is very hard to work with a system where most people just do not understand what's going on. Like the people in power are still very old.

You can educate a small group of people then they have to go share and educate the rest of the system. That is not easy, right?

Because you can bring someone out, they see what's happening and they come back and say, Hey, you know, this makes sense. But when they go back in there, they would then have to convince 200 other people that say hey, this is the right way to do things.

Ling Yah: Hey everyone!

Welcome to episode 93 part one of the So This Is My Why podcast.

I'm your host and producer, Ling Yah, and today's guest is Geoffrey See. Now Geoffrey has achieved many things in his life. Just to name a few. He graduated from Yale and Wharton business school. He was a Bain consultant. And he is the cofounder of a social enterprise that created the largest training program for female entrepreneurs in North Korea, which ended up being profiled in a Harvard business group case study.

He also helped to launch a blockchain protocol that had a 2 billion coin cap of its peak. He's a digital currency task force member and consumer protection report author at the world, economic forum global council for digital currency governance and an Ethereum foundation fellow. He's also a Kauffman fellow and now runs a Y Combinator backed startup focused on building DAOs to empower the next generation of investors, entrepreneurs, and creators.

Now we couldn't possibly cover everything that Geoffrey has done before. So in my interview, we focused on two things.

Firstly, his work with Choson Exchange, the pioneering social enterprise in North Korea that was provided as a HBS case study and reported in the likes of the BBC, the Financial Times, the Atlantic and the Straits Times.

And it was also by the way, cited as part of the rationale for Singapore hosting the first summit between Donald Trump and Kim Jong Un in 2018.

Secondly, we covered his current work with Poko in the web three space. As both of these works are quite distinct, I've actually split his story into two parts. That's why you have part one and part two.

So in part one, what you get is Geoffrey's childhood. What he was like growing up, how he ended up in the world of social entrepreneurship in of all places, North Korea. We cover things like what it's really like working there, why the women are considered to be incredibly entrepreneurial, what a north Korean power couple looks like and how he built trust in such a close society.

And as for part two, he talked about all things web3.

So are you ready for part one?

Let's go.

Geoffrey See: As a child, I used to have this very strange relationship with authority. When I was in secondary school, I actually skipped out in my last year , half the year. I did most of my studying at home on my own.

I didn't feel like school was the right place to learn the things I needed to learn.

Ling Yah: Aren't you Singaporean? So this is hugely unusual anywhere. Especially in singapore.

Geoffrey See: Yeah. It's kind of a strange path.

I went through this phase. Secondary school. There was a year where I was very competitive. Then there was a year where I felt like, oh, you know, what's the point of all this studying?

Is it just for grades? Is it just competition versus learning something?

I go through this weird existential questions around studying and schooling. Then when I got to junior college or high school, I skipped a lot of school. I actually managed to get onto a program in the US. At the Walton school in the University of Pennsylvania.

I spent a month away from school doing a program there. And I think really opened up my eyes in terms of the opportunities from around the world. Meeting people from so many different places gave me that thirst for exploring the rest of the world.

In junior college too, it was very much the same thing where I skipped a lot of school. Did lot of studying at home. Did fairly well, I think academically but just kind of always had that urge to challenge authority. So I remember trying to organize once inviting a series of political speakers to the school.

The principal called me to the office and he was like, no, you cannot invite opposition candidates to speak here. Why don't you invite someone from the ruling party? And I was like, what's the point of that?

right. I was so upset about it. It's a bit of a history for me back many years ago when I was still young, I guess .

Ling Yah: So when you were young, was it just this need to go against authority to see how far you could push, but no overarching idea of where exactly you wanted to be?

Geoffrey See: Yeah, I guess I had a soft kind of I guess a soft spot for the underdog. I always felt there is such an imbalance in power, in equity and I always felt compelled to say, oh, how do I support people who are excluded? How do I support people going the underdogs? And I think that's been a theme that after a while became remarkably consistent in my life. And it extends to the work I do today and in various parts in my career too.

Ling Yah: You said when you went to Wharton and that your eyes were open. Were there particular instances or people that allowed you to just be aware that there's so much opportunity out there?

Geoffrey See: Yeah.

So at that time, University of Pennsylvania is considered too dangerous to put high school kids because we are basically in west Philadelphia. It's a rough part of town. I think just for safety, for liability reasons, they put us up in the suburbs and then they drove us down every day through a part of Philadelphia called North Philly.

North Philly is rough. It's a very rough neighborhood. And I remember on one of the trips through North Philly to the campus, I saw a funeral march for a girl, that I, looking at a picture I would say maybe was like eight , 10 years old who got gunned down in the streets.

It left a really deep impression on me. I wanted to explore this issues of urban inequality and made my way to do my undergraduate in Penn and did a lot of work in west and north Philadelphia during my time in university.

Ling Yah: I noticed that you also set up Wharton's social impact major.

Geoffrey See: Yeah. So that was quite a fun experiment. We started out doing this experimental class under a very remarkable professor called Ira Hak, who pays a lot of attention to civic engagement and how universities interact with the surrounding community. THere's this whole thing on town end down.

A lot of universities tend to be very wealthy, very privileged and often in communities that are very underprivileged. You look at university of Chicago, you look at Penn to some extent, Stanford and East Palo Alto, Columbia and the Bronx area. you know, Very often they are in neighborhoods that are very underprivileged.

There is generally a question of how these places interacting with their neighborhood and whether they're contributing to it or in some way, actually resulting in gentrification and increasing the divide in the community.

So through this professor, we did a lot of work setting up a healthcare project. Basically kind of community based healthcare project in west Philadelphia. Can think of it as the first Dao in some way.

And out of that, I really liked this idea of learning from doing, and we built this major with the university, with the idea of incorporating service elements into broader concepts of , how does business make social impact? How do they have a broader social responsibility?

Ling Yah: Which sounds very much like a social enterprise. So was that your thought I'm gonna come back to Singapore, start some kind of social enterprise and help the people.

Geoffrey See: Yeah. I explored a few things before I did that. I taught for a while, I wrote some papers on corporate social responsibility and I thought maybe I should go onto an academic career.

I think what happened was that in between undergraduate and graduate school, I started a nonprofit called Chosen exchange to do training in the weirdest of places for women entrepreneurs in North Korea.

You know, North Korea at that point in time was very different from North Korea today.

It was very unknown. There was hardly very much written about it. I had somehow managed to make my way there many years ago to visit when I was interning in China.

Ling Yah: 2007, right?

Geoffrey See: This was 2007. What was really surprising to me was meeting a number of young north Koreans, especially this female university student.

I was very surprised cause I went in and thinking, oh, it's a communist country. No one is interested in these topics.

She told me that, oh, I wanna learn business to show that women can be good business leaders. It was shocking to me because I was like, oh, you know, you're a communist country and you want to learn about businesses. At the same time you have a very strong, personal ambition. Like you wanna prove something.

I think before I come into the country, I had all the stereotypes of it. And when I was leaving, she asked, how can I help? She said, can you bring an economics textbook the next time you came?

I thought, oh, that sounds simple enough. Turns out it wasn't that easy. I just thought, oh, here's something small that I can do to make an impact on someone's life. And that kind of got me started on the journey.

Ling Yah: I want to unpack that conversation you had in two ways. Firstly, I saw that in other interviews, you mentioned this particular conversation when you asked her about politics, and she also said "but politics is for men".

I wonder if you could just unpack that, just to understand what was the perception there, or even now for women in politics?

Geoffrey See: It's very interesting, right? We focus on women entrepreneurs in the country, mainly because North Korea is a very patriarchal society. When the Soviet union collapsed in the nineties, the economy collapsed in North Korea.

It was the women who went out to build the first kind of more autonomous businesses. Businesses that have characteristics of a private businesses, because a lot of the males had to stay in a government position.

So it was a woman who went out to participate in the market to make a living, to keep themselves and their families alive.

And that became the Genesis of early stage kind of market economy in North Korea. So that was a very interesting area to focus on because by the time we went in there, they had built more sophisticated businesses. They understood how to run an independent business. And, that's the reason why we had a focus on it.

So Yeah, this very weird I would say contrast where you have a lot of female businesswoman who are fairly successful in a country that is very patriarchal.

Ling Yah: So the men were already in politics and did not even help the women to run the business.

Geoffrey See: It's kind of very interesting.

Like we run this workshop. Some workshops are more entrepreneurial focused, some are more policy focused, where we have to educate government officials on what some of these things mean. Some of these changes that we're observing or we want to encourage them to consider.

And very often the ones where it's government focused would be 80% male and one that kind of business focus would tend to be I would say generally, fairly equal or even sometimes majority female.

So yeah, that's the contrast. It's quite interesting too, because there's this concept of a power couple in North Korea where the wife is in business and the husband is in government.

Because connections there do matter a lot , so there's this leverage navigating government matters a lot.

Ling Yah: What does business mean in the context of North Korea? Cause I was digging through the blog that you were keeping when you were at Poko and you would post about the different developments every single month.

I noticed that as you were talking about, for instance, the kind of lessons you were teaching, you had to take out all references to capitalism. And that for me was such a strange idea. I mean, business. How can you take out capitalism? What you have left?

Geoffrey See: I know. It's a very weird. You know, people there are not dumb.

I think they're smart. They're curious. They do wanna learn about rest of the world. I think they want change in their own pace. Some people want change to come faster. Some people are more frightened or uncertain about it.

They know that economies around the world have developed so much more quickly than North Korea. So they also have to catch up. But at the same time, I think there is that lingering concern, to make this transition in thinking is very difficult.

You know, you have a lot of people who clinging on to an older ideology and there is also the fact that they see themselves in competition with China and South Korea. They would be seen as, you know, what differentiates you from your neighbors?

And I think that's something that they always struggled with given the politics and the Korean peninsula.

Ling Yah: I suppose, How does the business survive and what's the relations with the politics? My understanding from my reading, correct me if I am wrong, is that you can set up your own business. But it's very much, they have to park it as sort of like an unofficial arm of the government and that's how they survive, but they can maintain a portion of the profits for themselves.

Is that how they always set it up?

Geoffrey See: Business study exists in a few different ways. Now I'm in the blockchain space and I see the parallels.

In North Korea you could have a business that say, I just do not set up anything official. I would just run it, do my thing. I provide a service, people pay me for it. Challenge of this kind of small unofficial businesses is that they are very hard to scale up because you need things like capital, lending. You need to register to own property, to buy property to have assets. So those are some of the challenges you'd face.

And then to do a more scaleable businesses, or one that has more private characteristics, what a lot of entrepreneurs do is that they say, oh, I find state-owned company enterprise to sponsor me.

I set up an entity under the state own enterprise. And in return, we have some sort of profit sharing agreement with the state own enterprise.

In the blockchain space we talk about DAOs decentralized autonomous organizations and you see the same thing where you have unincorporated DAOs who believe that, Hey, you know, I'm decentralized. Why should I be regulated? Why should I be registered?

Then your Dao say, Hey, I need to register because the reality is that things are messy and I still need to deal with a lot of off chain things, right. Where I need a legal entity to sign contracts, to own assets, to make sure someone can sue me or sue someone, if something goes wrong.

So that's this environment we saw in North Korea back then.

Ling Yah: I notice the timeline when you started Chosen. It was around December, 2008, but you were also at Bain between 2011, 2012. So how did that work out?

Geoffrey See: I started Chosen exchange on a very much a bootstrap budget.

You know, we had very little money. We raised some money through a mix of donations, some small grants. And, I did it for a while. Then at some point I just said, oh, I do need to go back and make an income.

I had an offer from Bain from university days, I took a year and a half off to work on what I was working on.

And I felt okay, it's time to go back there and, you know, also learn some skills and save some money. But I wanted to keep things alive. So I kinda ran it on the side.

And then when I was back in the US, we raised our first in sense institutional funding. We actually received a grant from some foundations.

And that allowed me to go back to work on it full time.

Ling Yah: What were the main concerns of say these foundations that you were working with, and I believe you also built partnerships with north Korean universities as well. .

Geoffrey See: Yeah. We were quite lucky when we started, because we had some funding from the foundations. We actually got some support from the US state department. The key concerns we had to raise it wasn't as severe at that point in time. But, you know, over time it became much more important.

But from the early days, one of the big things we had to do was sanctions compliant. Like making sure that we had a clear policy. We made sure that everything we did was in compliance with sanctions and how we do our due diligence around people we work with or people we involved in the program. It wasn't as severe at that point in time. But, you know, over time it became much more important.

I think the other part that was just very tricky was North Korea is a very, very uniquely difficult problem solve. It creates a lot of emotional responses, you know? So everyone thinks everyone in North Korea is bad. The government is brainwashed everyone. What we try to do is we have to say it's much more complex as a society, right?

So one is that most like, oh, they're entrepreneurs in North Korea. I didn't even know that. So trying to get people to understand these things was important and to let them know like what our theory of change was and why it was important.

I think as time passed, one of the big challenge was that there was both a loss of interest in the issue in North Korea.

People felt more and more helpless in terms of what they can do to make the situation on the ground better.

We saw a loss of interest in the North Korea issue over time from government or public policy angle.

I think the second thing is just that, there has never been a very coordinated or long term thinking around the issue. I think very often people were always looking for short term solutions. The only time they became a priority is when they were launching rockets and nukes.

Ling Yah: I was trying to understand that space and you were talking about, oh, people are surprised that there are entrepreneurs there. I was also surprised. So when I came across what you were doing, I dug into it. I learned that North Korea was focused very heavily at the time on hard infrastructure . So roads and equipment as a solution to development problems, as opposed to soft infrastructure, which is precisely what you were bringing in.

What's the rule of law? What are these monetary policies? How do you apply? Was it hard to get buying in? I mean, you got from the US, but was it hard to get buying from the locals as well?

You are a complete foreigner? Why are you coming here?

Geoffrey See: Yeah. It is difficult on all fronts, right? One is they are paranoid. They are always suspicious of any foreigner. I'm from Singapore. So the good thing is that, it's seen as a neutral country and it gave us a lot of credence in North Korea being from Singapore, being from Southeast Asia.

And we also bring that philosophy, Singapore is not the most ideological, at least on some of these things. We believe that you take approaches that work for the country in terms of developing the country and improving people's lives.

That said, they are paranoid. It is very hard to work with a system where most people just do not understand what's going on. Like the people in power are still very old.

You can educate a small group of people then they have to go share and educate the rest of the system. That is not easy, right?

Because you can bring someone out, they see what's happening and they come back and say, Hey, you know, this makes sense. But when they go back in there, they would then have to convince 200 other people that say, Hey, this is the right way to do things. So very challenging.

You are right. I think at least I'm still a government issue in most parts of the world.

Hard infrastructure is always easier to show a signs of success than soft infrastructure. Building the right system, building right ecosystem is a very long term thing. It's not something you can point to very concrete outcomes and it takes time.

It takes experimentation. Whereas if you build a building you point to as, Hey, look, I build a building. Who cares that the building is not supporting the ecosystem in the right way.

So I think always a huge challenge. And obviously it runs up against sometimes like many decades of ingrained thinking. That is always very difficult.

Ling Yah: So how did you overcome or work alongside this paranoia? How do you build that trust?

Geoffrey See: We try to understand it.

You know, as people, we try to understand these people. There are processes. We may not agree with a lot of the way things work. But the last thing we wanna do is say, oh, look, you know, it's just a bunch of crazy people.

We cannot understand what they're doing. So there is a rationale, there is a process for many things that happen there. And part of the trick of getting things done there is to understand how those processes work and why certain things that you wish would happen do not happen and learning how to navigate that system.

So that's something we did. So example is Like when COVID 19 struck, almost all projects in North Korea, uh, humanitarian, education came to halt. And we spent like close to a year persuading our partners to switch to online education.

And we became the first entity that was able to get online education up and running during COVID 19 with North Korea. And in the process we learned a lot of things, right? So, We learned that, you know, one is that there were a lot of stakeholders obviously were looking very closely as an experiment.

We had a very ambitious program. Once we said, we're gonna do 10 sessions on this very farfetched topic on digital entrepreneurship. And, you know, that failed, we didn't manage to get them on board with that process. And we learned that, oh, you know, because there are so many stakeholders, so the more lessons you give them to approve, the more likely one person is gonna say no.

But we went back and the next time we did it, we say, oh, you know, let's just get two sessions approved or four sessions approved at one time. So I think you learn how to work through the system to get to where you need to go by understanding the processes that underline the system.

Ling Yah: What about the early days before you were trying to get things approved, surely you had to start knowing who to approach. Who would be able to help you and be sort of like your supporters, right? How did you figure that out in the completely closed country?

Geoffrey See: I think it's a trial and error process, but it's also the right signaling.

So when we went in there, I think there were a few things that we were very particular on, right? We said we had a mission, you know, we are not being paid a lot of money to do the work we're doing. And then North Koreans at the time, they were used to the impression, you know, very often in all this communist transition economies.

There's a tendency to see foreigners as bags of money because it's a very poor country, right? So like whether it's China, Vietnam in early days, you go in there, they think foreigner means money. And I always have to remind them that I don't have a lot of money. I just graduated from university.

I'm doing this thing. We try to find locals that have the right intention, that they have the right interests and motivation for what we're doing. And it's a very different approach because some people say like, oh, you know, I'm just gonna find like the most powerful guy and I'm bringing in tons of money.

So they will speak to me and I'll get things done that way. I think turns out that that is not the most sustainable approach to getting things done in the country. And it's more often than not better to find people who just say, Hey, look you are interested in improving people's lives by sharing certain knowledge, encouraging certain areas of change. You find local partners who share interest and we cycled through quite a number of partners.

Over time we found the people that we wanted to work with that was a good fit for what we are doing.

Ling Yah: You mentioned earlier you had to also do due diligence on your partners. What did that look like?

Geoffrey See: I think the basic thing is definitely, always checking if they are from a sanction entity or if they are sanctioned individuals which is normally, honestly not hard because those people general tend to be so high level.

We never ever see them in the workshops. I don't think we ever had someone who was on a sanctions list. We had certain sectors that we saw as high risk at certain point in time. So things like financial sector, we say, okay, we're gonna stay away from it. We cannot teach technology, hard technology.

We can talk about startups in general and the sphere of entrepreneurship. How people think about technology, but we don't actually teach, like engineering or computer science or biology or something like this.

Ling Yah: Is it because the topics were too complex to cover?

Geoffrey See: I think very much more so because of the sanctions. There's guidelines around technology transfer and we have to stay very much within the boundaries of that.

I mean, you'll find that the north Korean is actually very good at technical topics. They have good math and science education but it is kind of more the softer topics where it is very hard to convey because, you know, imagine if you had lived your entire life in one system and now you say, hey, you know, learn this new system. You know, it's very difficult.

We did that once where we brought north Koreans to Vietnam and Singapore. And they were basically studying like how to create a law that allows people to buy land in the economic zones for industrial purposes. And we said, Hey, here's a auction mechanism.

This is a price mechanism. And that is the best way to make sure that you get the price value for the land and price it accordingly. And at the end of the trip, the north Koreans were like, this is just so complicated. We're just gonna fix a price for all the land, all the economic zones.

It's not because this, we are not smart. It's just that some of these things you grow up and is so familiar to you is actually very unfamiliar to people you know, who have grown up in an entirely different system.

Ling Yah: Just because I have a legal background. I'm curious.

I imagine you must have taught them things, concepts like rule of law, separation of power, which we've been totally foreign as well. Do you remember what the reaction was to lessons like that?

Geoffrey See: Yeah. We had a lawyer volunteer lawyer who actually led a session on the law in Singapore. So it's like you talk about commercial law and the North Koreans was so fascinated by it because for them it's more like ethics, right.

It comes from the top and basically everything's an executive order, right. And they were so impressed. One of the ladies was like, oh, I wanna study law. I want to go to Harvard law school one day.

So we gave her this book called I think Justice. It is a very popular book by a Harvard professor. I think Michael Sando and it's very interesting cuz we, we had a bit of a discussion what the rule of law means and how do we put it in a concept that people that could understand.

We said, oh, you know, it's when you can sue the government and win . That's how we, our simple definition of the rule of law.

Ling Yah: Her mind must have blown at that.

Geoffrey See: Yeah. It's, it's fairly new to them. I mean, firstly, in most cases they don't go to lawyers as the first part of call for a lot of things.

Ling Yah: When you talked about bringing these North Koreans, you brought them to like Singapore to Vietnam, to Malaysia. I read in your blog that the whole selection process was grueling as well.

And you were asking them what are future plans? Accomplishments. And it was culturally unfamiliar questions. So do I interpret it as being, they never really think about what is my plan?

What does my future look like? Is it just literally day by day survival?

Geoffrey See: I would say definitely it's not the case. I think people do think about their lives. But I think it's just that I was very used to at a time, you know, this Bain, McKinsey style interviews, very Western interviews, right.

People you go in there and they say, oh, what accomplishment are you proud of? What is your successes? So It's like kind of a bit boastful, very different cultural approach to interviews, right? And for many north Koreans they've never encountered anything like this.

So you have to do a lot of digging. You would have some that were done really impressive things, but they're just like, oh, it's not me. It's my team. Or the biggest thing I'm proud of is being a mother. I'm like, oh, but you also launched like this two super successful businesses. There is certain expectations when you do an interview.

And when you're not trained in the norms of it, you cannot just put out a question, expect people to know what to answer. Right. So I think that was what we learned in that process. There was a lot of work digging out and trying to understand them as an individual.

What they're doing. It's not something where I can just put that question out there and know that these people answer in a way that I expect someone who has been so used to this kind of questioning and interviews to be able to answer answer in the same way.

Ling Yah: So you brought north Koreans out, but you also brought people into North Korea. I read that you brought the ex finance minister of Singapore, ex-chairman Singapore international airlines. In 2014, you also brought this coffee expert who was treated like some kind of celebrity and everyone seemed to know about him.

I wonder what the process was like in just bringing foreigners into this really closed society.

Geoffrey See: Yeah. So, we normally go through a process where we brought volunteers in to run this kind of like 2, 3 day workshops on a bunch of topics. And we try to make it very interactive.

The way it works is that normally we start with a certain area of topics that we wanna work on. Then we put out a general call to volunteers. We come in, we do some screening to see who would be a good fit. And then we have to go through a process of applying for visas, for travel permissions and for the workshop itself to be conducted in the country.

And on the north Korean side, they would do an outreach. Some to alumni, some to different organizations that're relevant to the topic to see if people are interested in attending the workshop. So generally that's the way it works.

And then, you know, we bring them there. They spend two days running the workshops. Most of them go there as kind of like quasi tourists. So they wanna do something more than just sighting. They wanna engage in a country in a different way. But a big part is obviously to see the country and to get a better understanding of it.

That's kind of what we do.

This idea of grassroots or network type organizations really came about for me being that our volunteers came from all over the world, right. We have 200 plus lecturers coming from 30 plus countries.

It kind of just made me realize, oh, you know, here we have a common cause. Something that binds us together. But at the same time, a lot of these volunteers remain engaged often beyond the workshop itself.

So they go back, they share about what they did. Their experience helps contribute to a deeper understanding of North Korea in a global environment.

Ling Yah: So say I'm a listener of this podcast. I find this very interesting, I'm a lawyer. Can I reach out to chosen and be like, Hey, I wanna volunteer as well.

Geoffrey See: Yeah.

I mean, if it was pre COVID 19, yes. A lot easier. We're still waiting for our borders to reopen it will reopen someday. So we do hope to bring more people back in there when that happens.

Ling Yah: So I read during my research that one of your biggest costs was really just bringing the foreigners into the country. I wonder, what's the financing model that you developed to make this sustainable, because as you said, didn't have much money, you were losing interest. It sounded like everything was going against you.

Geoffrey See: Yeah. So when we started doing it, we talked to a lot of people who did projects in the country. And I say, we, because, you know, for me, it's like the work on North Korea belongs a bit to the past. You know, I still support the team. I volunteer now in that, but there's a team that runs it.

When I started, we saw this boom and bust, right? We had periods where there was some interest because maybe we felt North Korea's opening and people contribute money to programs, normally institutional funding from the EU, from different governments.

And then there'll be period where politics become very rough and they shut down all the programs. I thought it was really bad because you just do not have that institutional knowledge, relationship and branding to build success through projects in the long term. So I talk about understanding of how to navigate the internal processes.

Those are things that you lose every time you shut down a program. Relationships, people get burned, people move on inside the country and you never rebuild those kinds of relationships. So we said we want something that would last through thick and thin. And the way we did it was when we started our training program, we started as a volunteer organization.

So people covered their own costs to join us in these programs. And then, in some periods we were able to get some grants here and there to supplement that cost. So what it meant was that there was a fairly manageable burn rate and we could tie through this ups and downs and be consistent in delivering the programs.

Ling Yah: And I wonder, how did you measure the impact that Chosen was creating?

Geoffrey See: We used to have a database of close to 3000 entrepreneurs we have trained.

We try our best to track.

One is just attendance. Like, do people come back over and over again at a basic level. Post workshop, we run a survey to see what they've learned. What kind of exposure they're getting. And then in the longer term, we try to track some of those individuals that are doing some projects to see how those things are coming along.

Right. Did people launch a startup? Did they try to implement some policy change? Over time it got harder. As you know, we get a much larger database of participants but that's generally how we measure impact. I think the trickiness was that you know, funders come and go. Some periods, we had some funders and some periods we don't have them.

And so there really, isn't a very consistent approach to measuring impact because each funder has their particularities or area of interest. And one thing we struggle is how do we maintain our true north. What do we focus on that important to us as organization?

What do we measure?

And also having to measure things that sometimes is tied to one specific sponsor that wants to measure a program in a certain way.

Ling Yah: Focusing on that north star, is that how you kept your faith in the work that you were doing? Because I imagine must be been very easy and tempting to give up at any point in time.

Geoffrey See: Yeah, I struggle a lot because I hung on to the work for a long time. Hung up to it for probably almost a decade. Was sometimes a feeling like the world is passing you by, right.

Everyone's doing super exciting stuff outside. And honestly for North Korea, for the amount of work and ingenuity you bring to a problem, you could probably achieve 10 or a hundred X, the results outside because the smallest of things there is very difficult to solve .

right. Sometimes just getting a visa to go in you know, the most minor of things results in huge headaches.

I guess part of me felt like, oh, you know, I should have built an organization that could take care of itself much earlier and leave a lot earlier.

And then a part of me is like, oh, you know, I had to spend a certain amount of time to make sure that we could see things to a point where we felt happy and confident about it and it would go in a certain direction.

I think the biggest part that is most disappointing is less the work we do, which I felt overall is very meaningful, generated the impact that we wanted to see given the very modest resources we had, but the overall dynamics of North Korea's relationship to the rest of the world, where we hope that there was a pathway for North Korea and the west and South Korea to get the objectives. That there is a pathway for integration.

I think that over time people just get further and further away in terms of their positions.

And I wonder if we've crossed this point of no return where really just to envision some sort of settlement to the Korean war. A peace treaty kind of re-engagement with the US and North Korea, for example. You know, whether we've gone past that point.

Ling Yah: What is the thing that you're proudest of having done Chosen?

Geoffrey See: In terms of chosen exchange, for us, we've always proven time and again, that many things people thought was impossible to do in North Korea, we managed to do it.

So when we first started everyone say, oh, you cannot meet the North Korea to take part in the program again. It's not possible to do it. We actually managed to get that done. which We managed to do it very consistent. So we could build a rap port and build a constituency in the country.

When we first did the online education program, many people from outside were against the idea . So say, oh, you know, once you do this online program, the north Koreans would never invite people in to do programs ever again. And I'm like, you're kidding me.

Right? They are not gonna invite people in because of COVID 19 and who knows how long they're not gonna be able invite people in. And we managed to push through and get it done.

Given the scale of the program that we do is very small with the resources we have, we can at least say that we have proven certain things are possible.

And I think that's the biggest value that we've done.

Ling Yah: So one final question before we move to after Chosen. You've mentioned that you had certain people who were tremendous supporters in what you were doing, role models as well. Like professor Moon Chung-In, George Yeoh, Dominic Barton.

I wonder how did they help you? Why were they your role models?

Geoffrey See: George Yeoh, our former foreign minister and globally a very well recognized politician. He basically helped us by being very supportive. Joining us on a trip to North Korea. Providing us a lot of advice and connections with people that were very helpful and overall giving us showing us the moral support in a period where this was a very difficult issue to work with, right.

People don't wanna be associated with difficult topic. And I think he had a lens on history. He's a big history buff, and he's able to view things from that broader sense of, of history and was just very humble. I remember going in there and he went like five, six days.

He brought his wife, wanted to see how North Korea changed since his last trip, like almost a decade ago. And at the end of the trip, he gave a speech to a group of university students. It's very rare when you see a foreigner come in and is able to articulate over the course of five, six days.

He's been absorbing everything. Hearing what people have been saying, you know, trying to understand what's happening.

And he gave this speech that you could just see the north Koreans nodding along and be like, this guy really understands us. This foreigner who has never lived here is now, saying things that we understand and we buy into it. We believe in it. He's talking about how he felt North Korea should move forward.

So that's him.

Moon Jong in. He used to be the national security advisor for a number of south Korean presidents, mainly on unification issues and I had the opportunity to work with him closely as a member of the economic forums global future council on Korean reunification.

For me, it's just amazing because here's someone who has dedicated many, many decades of work to the very difficult task of trying to in a sense, reconcile both Koreans.

And so someone I look up to for that effort and energy and determination to make it happen. Dominic Barton helped us on a number of issues related North Korea. Had a passion for it having served as the head of the McKinsey office in Korea. That was his introduction to Asia

Ling Yah: Was n't he global managing director of McKenzie?

Geoffrey See: Yeah . He later became global managing director of McKinsey, but he got his start in Asia through the career office. So he's always paid a lot of attention to the Korean issue.

When I first met him in Switzerland probably a decade ago , I told him what I was doing and it was just super fascinating.

He said, you know, we need to go out and chat so I can learn more about Korea. We did that. We went to a restaurant, I explained to him what I saw and what I'm hearing in North Korea. He was just remarkable listener, took a bunch of notes.

At some point he was like, oh, let's invite the north Koreans to the St. Gallen symposium.

This is one of the best forums I've been to in Switzerland and we made it happen.

He's such a humble guy. Such a intellectual Omni vault.

So when the North Koreans came in, he started saying, oh, you know, you guys, you have a national philosophy.

He's got Juche blah, blah, and made some joke about it. Wow, this guy knows his stuff. Which is amazing. Very helpful person, very humble, someone I look up to. I can learn so much from.

Ling Yah: You start in December of 2008, you stopped being chairman in December, 2019, which is 11 years worth.

At what point do you realize that it was time for you to move on to the next step? And did you know where you were going?

Geoffrey See: The period 2016 and 2017 was very difficult. We were scaling up our impact up to the end of 2015, 2016. I remember I was coming in very confident. We had an amazing year in 2015. Lots of great programs and we felt overall things was hitting in the right direction.

Then on January 6th, the North Koreans did nuclear tests. And the reaction after that was bad because there was a ratcheting up of sanctions of pressure. And in turn, on the north Korean side, they reacted by being more hardline and doing more tests and missile launches.

We went in this two year cycle of just after escalating violence.

You know, I remember there was this whole fire and theory. I know if people remember that when Donald Trump was threatening retaliation on North Korea and North Korea the US.

It was very depressing two years, right? You saw everything you built just kind of unwinding.

I told myself that I would see things through these two years. And then at the end of the two years , we went into this brief detente , the summit between Donald Trump and the North Koreans. And I at least wanted to get past that period. Hopefully things will be on a better footing and see the organization through to that point.

And I managed to do it. At that time I decided it was time to move on. Also the recognition that the success of what I've built is that it goes on and runs itself. I shouldn't have to be too heavily involved in the work that comes next. We successfully made that transition.

There's a lot of learning and you know, you need to find the right people, right. you know, I've done it in a way that both myself and everyone involved could remain involved, but not have it become full time work for anyone.

Ling Yah: Was it difficult for you to let go?

I imagine you feel as though your identity was tied to this and suddenly you are letting it go and someone else is running this, which is essentially your baby.

Geoffrey See: Yeah. Definitely. So I think, I think That was the thing I struggle with the most. right. There was so many points where I was like, oh, you know, I should move on.

But I just felt so much responsibility towards what I've built, it was so much a part of me.

Now in hindsight you just feel like, oh, 10 years, isn't that long a part of your life, but there's a part of me that felt that, oh, it's giving up so much that I could never move on. That this is what I am known for.

In hindsight I realize that some things you have to pivot faster. You have to make decisions around those things faster because this is just the reality, right? There are things that you can change and there are many things you cannot change.

What we couldn't change was the general dynamic or interest on the north Korean issue or the willingness of major state actors to come together on an agreement on the future of the Korean peninsula. Those are just issues that are too big for us to have a very direct influence on.

Ling Yah: And that was the end of episode 93 part one.

The show notes and transcript can be found that www.sothisismywhy.com/93. If you've enjoyed this episode, could you take the time to just head over to apple podcast and leave a rating and review? Every review really helps this podcast grow and reach a wider audience.

And don't forget to head over to tune into episode 93 part 2 to learn all about Geoffrey's journey into the web three world.

How his extensive working exposure in places like North Korea and Vietnam meant that he was acutely aware of the need for a medium like Bitcoin. The problem he is trying to solve right now with Poko, why he's currently working with the Kazakhstan government and so much more.

So do stick around and head over to listen to part two, right now.

STIMY 93 Part 2: Geoffrey See [Co-Founder, Poko]

===

Geoffrey See: One example was in 2016, 2017, when the whole tensions arising off Korea. Many banks said for your nonprofit, we cannot bank for you. You are in compliant with sanctions, you have done nothing wrong, but you are just more risks than it's worth for me. I remember our bank account was shut down in the US and the bank had written the money to us as a check.

We couldn't open another bank account because everywhere you go, they'd be like, why you open a bank account? Or you do say because the last bank shut down my account?

All the banks would just be like, oh, okay, you know, high risk. I don't wanna do it for whatever small amount of money you had.

So I was running around this paper cheque. I was going from branch to branch. I was literally crying at the branch and people were just like, no, we can't do anything about this. We cannot cash your cheque because you don't have a bank account to cash it into. So you feel what it was like to be locked out of a system, to be excluded.

Eventually we managed cash the cheque because I went to a payday lender.

You are in this line with all these people that you felt kind of like represented a whole bunch of stereotypes. You could see the single mom, the guy in front of you shaking probably on drugs.

I was in a very rough neighborhood and, after a lot of discussion, they'll find out, okay, you know, we're willing to cash the cheque. They took a huge percentage out of it!

That was my first experience, knowing what it means to live on the margin, to be excluded.

We talked about underdogs at the start of the show. Now I felt like, okay, this is what being an underdog in life feels like. To be excluded from systems, to be at the control of other people who essentially make decisions about how you live and how you do things by virtue of the infrastructure they control. Can you imagine someday you wake up and you cannot use any bank?

You cannot transfer money. You cannot use credit cards. You cannot park your money or send it to someone digitally. That is very scary. And it does happen to people for good or bad reasons.

That was also for me, understanding why blockchain web3 is important in so many ways. You realize that going through all this intermediaries means ceding control or power to someone else.

Ling Yah: Hey everyone. Welcome to episode 93 part two of the So This Is My Why podcast. I'm your host and producer, Ling Yah, and today's guest is Geoffrey See. If you haven't already listened to part one of Geoffrey's story, please do. In part one, we covered his childhood, how he end up founding the largest, most successful social enterprise in North Korea.

And he actually peels back the latest to show what North Korea really is like behind all the posturing and narratives put forward by traditional media outlets. For instance, why are north Korean women so entrepreneurial? How do they think about concepts like the rule of law? What constitutes a North Korean power couple and how did Geoffrey find partners, raise funds and build trust in a closed society like North Korea?

And as for this part?

We continue with Geoffrey's journey this time into the world of web three. How do he get into it? How has his extensive working exposure in places like North Korea and Vietnam influenced his understanding of a medium like Bitcoin? Why is the problem he's trying to solve with Poko?

Why is he currently working with the Kazakhstan government and so much more.

But before we start, if you've been enjoying this podcast, could you please take a moment just to head over to apple podcast and leave a rating and review? Every review really helps this podcast to grow and reach a wider audience.

Now, are you ready for part two?

Let's go.

What I found so fascinating about your profile is that you were working so extensively in North Korea, and now you're focused very deep in the web three space.

The first question would be, how did you first hear about this thing called web three and decide that this was not a scam and something you wanted to go into?

Geoffrey See: I think it's very interesting because working in places with no rule of law, very limited governance, very low trust, helps you think a lot about the value of blockchain.

For most people in societies where you have a good rule of law, you don't face these issues.

I mean, there will always be people who are left behind, but for most people, it's a toy, right? It's not something that you need.

Ling Yah: So interesting the way you said that, cuz it reminds me of so many people who would say I go to Vietnam and there's tremendous adoption of crypto because the value of the currencies is so fluid.

Geoffrey See: Yeah. Yeah. So it fills in gaps, right? It fills in gaps in governance. I now run a startup we just came out of the recent Y Combinator program. Poko focus on helping people build DAOs or decentralized autonomous organizations.

So what it is is more collaboration between different parties in a way that's more trusted.

A lot of them will obviously use it too, because they want to conduct some for enterprise payments in a accountable manner on crypto rails. But how I got to this journey was that when I first started working in North Korea issue, I was also an affiliate researcher at MIT.

Our work started because of a currency reform in North Korea. The government said change the old currency to the new currency, and you can only cap it at $500 for each person. So what it meant is that anyone who was involved in business lost their savings or their income and I was in MIT and I was talking to other people and say, Hey, you know, how do we protect entrepreneurs from this problem?

And at the time it was 2012. Bitcoin was not on everyone's radar, but someone was just like, oh, you check out this thing called Bitcoin. You know, might be really interesting. So I read everything I could about blockchain. I thought it was like super fascinating. The end of it I thought, no one is ever gonna buy Bitcoin.

The reason why I thought that way was I thought the technology was amazing, but I believe money is money because people believed it is money, right. It is a belief system. And I didn't know if the prerequisites for Bitcoin becoming something like this would exist.

So that was my first exposure.

We didn't end up doing anything with technology. But then in 2017 the idea of blockchain really stood with me. So in 2017 I joined uh, team that was spinning out this protocol called Zilliqa.

I joined the parent company as the chief strategy officer, and then we spun out this protocol called Zilliqa with the national university of Singapore and got it up to fairly successful, decent ecosystem there.

Like a two, 3 billion dollar coin cap protocol. And then I also helped them establish an exchange that was regulated and licensed by the central bank of Singapore that was trading essentially private securities in a regulated manner. So that's a bit of my journey.

Along the way, there are many periods where I saw the value of this alternate system that people could operate on.

One example was in 2016, 2017, when the whole tensions arising off Korea. Many banks said for your nonprofit, we cannot bank for you. You are in compliant with sanctions, you have done nothing wrong, but you are just more risks than it's worth for me. I remember our bank account was shut down in the US and the bank had written the money to us as a check.

We couldn't open another bank account because everywhere you go, they'd be like, why you open a bank account? Or you do say because the last bank shut down my account?

All the banks would just be like, oh, okay, you know, high risk. I don't wanna do it for whatever small amount of money you had.

So I was running around this paper cheque. I was going from branch to branch. I was literally crying at the branch and people were just like, no, we can't do anything about this. We cannot cash your cheque because you don't have a bank account to cash it into. So you feel what it was like to be locked out of a system, to be excluded.

Eventually we managed cash the cheque because I went to a payday lender.

You are in this line with all these people that you felt kind of like represented a whole bunch of stereotypes. You could see the single mom, the guy in front of you shaking probably on drugs.

I was in a very rough neighborhood and, after a lot of discussion, they'll find out, okay, you know, we're willing to cash the cheque. They took a huge percentage out of it!

That was my first experience, knowing what it means to live on the margin, to be excluded.

We talked about underdogs at the start of the show. Now I felt like, okay, this is what being an underdog in life feels like. To be excluded from systems, to be at the control of other people who essentially make decisions about how you live and how you do things by virtue of the infrastructure they control. Can you imagine someday you wake up and you cannot use any bank?

You cannot transfer money. You cannot use credit cards. You cannot park your money or send it to someone digitally. That is very scary. And it does happen to people for good or bad reasons.

That was also for me, understanding why blockchain web3 is important in so many ways. You realize that going through all this intermediaries means ceding control or power to someone else.

I go to Vietnam and work with startups and we've seen incredible startups in Vietnam, in the play to earn space. Startups like Axie Infinity, Wolf fund games, Teton arena. They have managed to scale globally, fairly successfully as a Vietnamese startup in a very quick span of time. If you were to launch a traditional startup in Vietnam there are many things that poses barriers for you.

An example is startups here cannot directly get access to the Stripe payment platform. So they have to create a company in Singapore. They have to create a bank account in Singapore. Very often the banks there treat it as high risk, so they might end up shutting down your bank account. And then you're cut off payments.

Or I helped a startup here who Facebook kept blocking them from doing ads and setting up a business account. They were a chat bot maker. They had done nothing wrong. So I put him in touch with a Facebook manager in Silicon valley. He looked at what they were doing and he said, there's no reason why we should be blocking you, but you have to go through all these platforms in order to assess your market.

Because that's just the nature of the internet today. I see the value of this whole web 3 community of, and the ethos of this intermediation of self sovereignty. I think it can bring value, especially to communities that are marginalized.

So when we are at Poko when we are creating our DAOs, we talk to a lot of users in places like Latin America, India, Vietnam and I believe there is a strong use case in emerging markets that in some ways should be stronger than places with a good rule of law, high degree of trust and abundant capital in the startup ecosystem.

Ling Yah: The idea that ethos behind blockchain is very beautiful. I mean, who doesn't want to cut out the middle man who doesn't wanna have full control what we are doing?

I was speaking to a lawyer who works at avalanche and he said that I'm all for users taking more responsibility for their actions. Completely. But at the same time, I spoke to Phil Libin who co-founded Evernote. And he said, I think blockchain is complete bull because in what world, can it be fair that you can never turn back a decision that's been made?

Cuz scams are everywhere. If someone comes in, puts a gun to your head and say, sign all this to me, you can never change it, but no one can ever, ever do anything. And the idea that can never overturn something so unjust is insane.

His thought at the time was the idea is amazing, but maybe the future is not in this thing called blockchain.

And I wonder what your thoughts were in this?

Geoffrey See: I think it's good points. Question of like, how do we build open systems? Can we build open systems without by true intermediaries? I dunno.

I mean, what we've learned over the years is you think of all these brands we used to trust so much. Like Facebook, everyone's like, oh, you know, they're so amazing. They're startup, everyone looks to be, and inside they became the villain. They're like, oh, look what they're doing with your data and all that.

Ling Yah: It's almost like an inevitable cycle.

Like all big tech will be hated at some point.

Geoffrey See: Yeah. And I think there are places where there's a lot of trust in governments and over time people lost trust. There are places where trust is still on the rise. So you have a lot of variety in the world.

It's very hard to say that there's one system that works for everyone for a planet of 7 billion over people. I believe that there are places where you don't need a blockchain. There are places where you have systems that are by and large fair, and serves most people in a pretty decent manner.

And there are places where you don't. And I think where Web 3 technology come in where this intermediation comes in is that it provides an option for people. It's not meant to replace monetary systems. It's not meant to replace every single organization. It's not meant to replace every single web two product, but it will be a huge complement for many people that need something indirect.

They don't want to be controlled by other platforms. I think you will find a space among that community.

Ling Yah: I want to talk more about DAOs.

As Bankless said, DAOs are growing exponentially and you have dived straight into it and that's precisely what Poko about.

For those who aren't familiar with this concept, decentralised autonomous organizations, what are they and what can they actually do?

Geoffrey See: We actually take a very broad definition of DAOs.

We see it as what we call blockchain based companies. There's a number of elements. DAO stands for decentralized autonomous organization, which in this space is kind of funny because most of them are not necessarily decentralized. Quite often, not autonomous. But they organizations.

So where does the DNA come from? The idea is that decision making we decentralize. So it's comes almost like a voting community executions autonomous. I do not need to trust other people to be able to execute certain decisions as a community. Normally decisions involving capital and the use of treasury or other changes to a protocol and so on.

So, in terms of technology, we're not there yet in terms of how we deliver on those things. But what we see among the view reach out to us is a mix of things, right? So some people are like enterprises who have a very decentralized base of customers or decentralized team.

And they say, I wanna move my payments onto crypto risks. I wanna essentially do my banking or crypto risks. That's one example.

Then we have people who say I want tokens to represent some form of ownership or interaction within a community. And I'm organizing my processes, my organization through the use of token format.

And then you have people say, oh, I really want decentralized decision making. I think that's actually quite a minority. But you find that their aspects they're decentralized, right? Whether it's in terms of self custody of money or in a sense of like I want my ownership records, my membership records to be spread out among more people and allow them to participate in new ways. So those are DAOS.

Think of them as companies that very often come with your own bank, your own payment processor, and then some form of like way to track ownership and to make decisions collectively as an organization.

Ling Yah: And there are also many different types of DAOS as well: investment, VC, community.

What is the difference between say an investment DAO and a traditional VC?

Geoffrey See: I've been involved with a few VC type DAOS. Investment DAO can go from something very simple where we wanna spin up. Say you, me and a few other friends, we wanna spin up a special purpose vehicle and we will collectively make decisions on the assets we buy or what we do with those assets.

So that's an investment DAO and you can go all the way to like VC type DAOs, where the idea is people wanna create a bit of an ecosystem where people come together and contribute collectively to decision making around, say what to invest in. They contribute their knowledge into the pool in a way that normally has some form of reward mechanism that then incentivizes people for their contributions.

So they wanna create kind of a bit of internal economy for knowledge, for leads, for expertise, for due diligence and so on. So those are experiments that I have been involved in and seeing take place.

I would say the difference is that a VC is traditionally very hierarchical. You're very core set of partners that make the call. VC Dao is trying to create new ways in a sense to crowdsource knowledge, expertise, and effort to achieve its purpose.

Ling Yah: So the way that a Dao function is really it issues governance tokens, and you could be, you have one token, one voting power. You mentioned something interesting called the reward mechanism. Could you give some examples of what that looks like within a DAO?

Geoffrey See: Yeah. So for example I'm involved in this Dao called VC 3.

It's set up by a bunch of people from this fellowship called the Kaufman fellows. They're all VCs in their professional life and they issue a token that allows for voting. And the idea was that, oh, if you say, for example, I need a reference for this founder that we are due diligencing.

Does anyone know someone on all that? And I put out a bounty say, I'm gonna give 20,000 VC 3 Dao tokens for anyone who can get a good reference in so that we understand whether this is someone worth investing in or not. So that's an example.

Or say, like, we want someone to be involved in some aspects of treasury management and here's some tokens that we're issuing so that people have an incentive to do so.

I think in terms of the value of the token everyone is still trying to figure it out, right? It's like sometimes we are like, well, what exactly are these things for? It's interesting, you know, it's an experiment. But I think a lot of this are still work in progress. We are trying with different approaches around this.

But I do believe there's a strong value to rethinking how we manage and own organizations and how we involve a broader set of stakeholders in owning what we build. Traditionally, when I think of giving up equity, it is very tedious and time consuming. And it's very low level trust.

If I just go out and say, Hey, let's go sign a safe note, an investment note with like 2000 people say, I want my customers, I want my community, I want influencers. I want all those different stakeholders.

But what you can do with the token format is that you have a universal language that people in the space understand whether you're from Argentina, Vietnam, Kazakhstan, Europe, US. People start to understand the token format and it's relationship to the entity. And they can say, Hey, I want this 2000 people from day one to be a part of this community, to own part of it and be involved in it in some way. And I can give them tokens as a way for them to get there. So it's very powerful as a go to market mechanism.

It is very hard to do that traditional instruments today. This is not really how you think of a public company. Because it could be just very early days, right. This could be like a day one company or a day 90 company.

But it is able to build that broader kind of mobilization for people. So I believe it's creating new ways of approaching the market. And I think trying to fit it into a definition of what we understand today can end up missing the point about some of these new technologies.

Ling Yah: I, when I first heard about the concept of Daos, I thought it was just fascinating, the broadening of allowing anyone to be involved in the running of say a company in a way that you have never been able to. But then as I got more involved and I play this play to earn game, they have this Dao and you vote on Snapchat and they give you some kind of reward as a return.

I realized that I wasn't so much caring about the proposals. I just wanted the rewards and I just don't care. I just filled out one answer. Yeah. And it brings me to mind the fact that the question of how do you ensure I suppose the quality of the kind of responses you're getting from the people, because is it even possible to do that?

Geoffrey See: Yeah, I think there are many people trying to software in, in different ways. I think the one that I do like, and we also kind of like playing around in our mind in terms of down the road.

One thing I'm very big on is this idea of taxation with representation. How do you fund public goods in a way that's align with the preferences of users and be more directly engaged with them.

And I think the idea behind it is that one thing that I like is tokens that are earned. A lot of people who buy are speculators and the value they bring is like liquidity or price discovery and all that.

But beyond that, they're not necessarily the most involved in a community. Right. So everyone to move away from like, Hey, this Photocracy where, I just go in and buy a bunch of tokens to people who say, oh, you are involved. And there's a way for me to measure that you are actually involved in the way I want you to be. That you are bringing value in a certain manner.

And as a result of that, you can unlock your tokens or achieve your tokens. I think that's one model I think you know, I like to see more. Where people are rewarded for doing things that are very much in line with bettering the organization or the community and earning those tokens rather than buying it.

There are many other ways we could try to solve these problems, like reputation, different ways of voting. Yeah, so lots of experimentation trying to figure it out.

The other big problem is these things take a lot of time.

How many side jobs and day jobs can you handle at one time?

I think we do need to think a bit about how exactly we want people to be involved in the DAOs to understand if it's the right mechanism or how to design the right mechanisms then.

Ling Yah: You mentioned VC three earlier. You're also involved in the Bankless DAO, the Orange Dao.

Have you noticed any particular hallmarks that make a quote unquote successful Dao?

Geoffrey See: Honestly the ones that we work with, we work a lot more with like startups, right? They're very established, very highly decentralized dials. And most are people just building a company or a community protocols.

For them a big part of what they wanna use is just tokens as a way to build interaction or they want to use crypto for some form of payment or fundraising. I would say success is very different, right? From what other people are doing and what other people are doing.

So for them there was still always be a core set of management team that have to drive the thing forward. They may have decentralization as a longer term objective, progressively moving towards it. Or they may not have that in mind. We think of it as like blockchain based companies.

They're successful in the sense that they achieve the objective, right? They want to in a sense, own their own bank account, their own payment processor. They want to accept and send payments to crypto because they believe in it. It helps them save costs in some way, or gives more options to their users.

Then you have people who are trying to build something to experiment of new models of delivering a service or work.

We have looked at defi protocols that have actually been very successful in the sense that, you know, they survived the latest meltdown in fairly good shape compared to their centralized regulator and registered entities counterparts.

And so, those have been successful in their own way. They've shown robustness to certain situations. Does it work for every kind of business or cost? May not always be the case, but I think it points towards the potential of what we can unlock here.

Ling Yah: One of the things that I noticed, which was a big issue when I first saw this thing of Daos is the fact that, well, okay, this is very exciting, but what's the legal structure behind?

Does it mean that everyone is open to unlimited liability? How do you own assets? And that is precisely the issue that you are solving and you also work with the Kazakhstan government as well and I would love to hear how that happens.

Geoffrey See: We had just finished our Y Combinator demo day, and we did our subsequent fundraise.

We saw that a lot of DAOs, the regulations in this space was just getting heavier and heavier. And I think it's important for anyone in this space to have a view and thinking towards it. And it's not because it's so early. It's very expensive and needlessly complicated and intimidating to most people, not just doing DAOs, but just anything in this space, right.

It's getting like, oh, there's so much regulations that I need to think of or regulatory uncertainty. And so we say it's better that the Daos have a legal form. I mean, they need a legal form for many things, right. They need to sign contracts. They need to have limited liability.