Powered by RedCircle

Listen at: Spotify | Apple Podcast | YouTube | Stitcher | RadioPublic

Welcome to Episode 22!

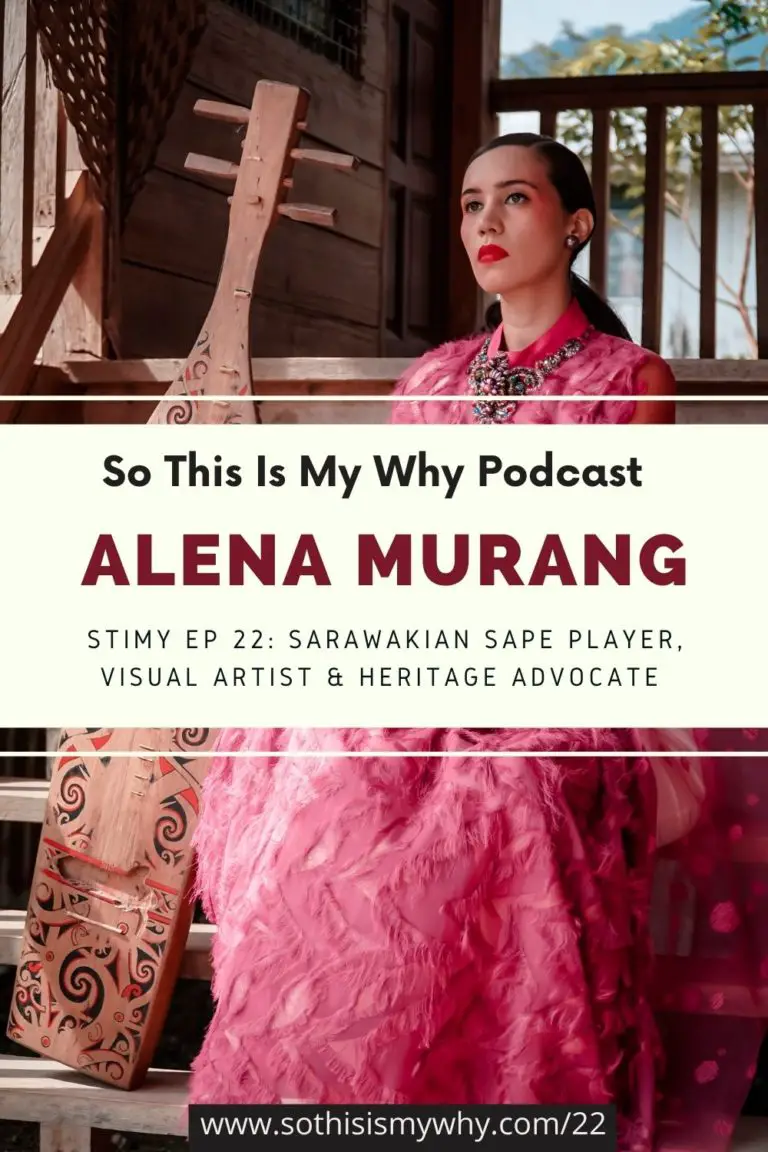

Our guest for STIMY Episode 22 is Alena Ose Murang.

Alena Ose’ Murang is a Sarawakian sape player singer, teacher, speaker, social entrepreneur, visual artist & heritage advocate. Born in Kuching, Sarawak, to a Kelabit father, Ose Murang, and English-Italian mother Valerie Mashman, Alena and her older brother were immersed in their local heritage from young including dance and the local lute instrument, the sape. While Alena has never formally studied music, she answered her calling to be a keeper of stories for her people and in 2016, released her first EP, Flight – a collection of traditional Kenyah & Kelabit songs.

Since then, Alena has performed at many renowned world music festivals including the SXSW (USA), Colors of Ostrava (Czech Republic), Paris Fashion Week (France), Rudolstadt Festival (Germany), OzAsia Festival (Australia), and Rainforest World Music Festival (Malaysia). She was a youth representative at the UNESCO Youth Forum in Paris, and UNESCO Asia-Pacific for her work in intangible cultural heritage.

Alena also started Kanid Studio (previously known as ART4 Studio), a social enterprise that uses art and music as a medium for positive impact, grounded in indigenous community values that are strong in the longhouse villages.

Alena Murang has been featured on Nat Geo People, Channel News Asia, Asian Nikkei Review, NPR Radio, BBC Radio 2, Radio 6, CBC News, Discovery Channel, Double J, etc.

Who is Alena Ose Murang?

Born in Kuching, Sarawak to a Kelabit father, Ose Murang and English-Italian anthropologist mother Valerie Mashman, Alena shared:

- 3.20: What is was like growing up in Kuching & being immersed in the local culture including visiting villages, studying rituals like basket weaving & hiking

- 6:08: How at the age of 6, Alena & her cousins began to learn the arang kadang (long dance) & solo Hornbill dance from her aunties, before half of them decided to pick up the sape

- 7:26: Getting Uncle Mathew Ngau to teach them the sape & why that was such a contentious issue because of their gender

- 8:46: The history of the sape, and difference between the “spirit” & “human” sape

Identity

Being of a unique heritage, we also chatted about her struggles with her identity

- 16:04: Deciding on the course to study at the University of Manchester

- 17:45: Identity & heritage

- 20:13: Her love of art

- 21:35: Studying fine arts at the Lasalle College of the Arts

- 22:37: Why Alena’s fine arts teacher did not encourage her to pursue art as a career

Finding Her Why

Feeling lost after being told by her art teachers to not be an artist, another opportunity soon came knocking:

- 23:59: How Alena ended up on a US tour with the Diplomats of Drum as a sape player

- 25:58: Her discovery of how the sape could move people

- 26:31: Why she became a fellow with Teach for Malaysia

- 28:28: How she started her social enterprise, ART4 Studio (now known as Kanid Studio)

Entering into the World Music Scene

In 2016 when Alena was 27 years old, she became a full-time musician, and we explored:

- 30:35: The push factor that led Alena to pursue world music as a full-time career

- 31:53: How Alena produced & released her first EP, Flight

- 33:45: Working with life coaches

- 35:15: If Alena was ever plagued with imposter syndrome

- 35:44: When Alena knew that she was doing exactly what she was meant to be doing

- 36:44: How Alena ended up participating in the Norway Fjord Festival (Scandinavia’s largest traditional music festival) & Paris Fashion Week

- 38:47: Whether Alena ever felt she had to get out of Malaysia to grow her musical career

- 41:48: Working with her village elders

- 43:09: Being a part of the Small Island Big Song Austronesian production

- 44:53: Why beads are so important to Alena’s indigenous heritage

- 46:56: How COVID-19 has impacted Alena & her career

- 49:14: What listeners can do to help Alena & any other world musician

If you’re looking for more inspirational female stories, check out:

- Red Hong Yi – An inspiring, entrepreneurial artist that pivoted from being an architect to a sought-after artist that paints without a paintbrush;

- Freda Liu: Business radio host of BFM 89.9 in Malaysia, Author & Emcee

- Chye Neo Chong: First female MD of IBM Malaysia

- Hillary Yip – An inspiring 15-year-old CEO & Founder of MinorMynas, an educational platform that connects children with each other. A company she founded at the age of 10 despite also facing intense bullying in school. Hillary is a true testament that you can achieve anything you want regardless of age & adversity!

If you enjoyed this episode with Alena, you can:

Leave a Review

If you enjoy listening to the podcast, we’d love for you to leave a review on iTunes / Apple Podcasts. The link works even if you aren’t on an iPhone. 😉

Send an Audio Message

I’d love to include more listener comments & thoughts into future STIMY episodes! If you have any thoughts to share, a person you’d like me to invite, or a question you’d like answered, send an audio file / voice note to sothisismywhy@gmail.com

External Links

Some of the things we talked about in this STIMY Episode can be found below:

- Alena Murang: Website, Instagram, YouTube, Facebook

- Subscribe to the STIMY Podcast for alerts on future episodes at Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Stitcher & RadioPublic

- Leave a review on what you thought of this episode HERE or the comment section of this post below

- Want to be a part of our exclusive private Facebook group & chat with our previous STIMY episode guests? CLICK HERE.

PS:

If you want to get an alert about upcoming episodes & be the first to know about freshly booked guests, subscribe to the newsletter below!

I’m constantly sending out information about guests & also asking for questions from my subscribers.

You don’t want to miss out!!

Ep 22: Alena Murang - Sarawakian Sape Player, Teacher, Visual Artist & Heritage Advocate

Alena Murang: I think because I was so rooted in my Kelabit heritage through music and through art, but at the same time I would be treated differently. Like I wasn't from Malaysia, right?

Until today, people are so shocked that I'm Malaysian. Even in Malaysia, I'm shocked that I'm Malaysia. They're like oh, where are you from? Like, oh I'm Malaysian, are you sure?

Are you sure?

And people are so shocked that I speak Bahasa and so, yeah, I still get that. So actually I was really looking forward to leaving Kuching.

I mean, number one, I think a lot of us were looking forward to leaving Kuching because it was a bit small.

But also I was looking forward to going to England because that's where part of my heritage is from, and I was like, ah, maybe finally, I can fit in over there.

But no, people in England thought I was Asian. I mean, I am, but they would call me Asian and wouldn't see me as British.

Whereas people in Malaysia wouldn't see me as Malaysian. So, yeah, it was quite hard, like my late teens and early twenties, but I think at the end of the day I just found that I resonated with Malaysia or Sarawak most.

Ling Yah: Hey everyone.

Welcome to episode 22 of the So This Is My Why podcast. I'm your host and producer, Ling Yah, and today's guest is Alena Murang. A Sarwakian sape player, singer, teacher speaker, social entrepreneur, visual artist, and heritage advocate.

The snippet you heard earlier is from a song called Midang-Midang. An old Kelabit song handed to Alena by her grandaunty Tepu' Ira. And a song we also talk about in today's interview.

Alena is half Kelabit-Dayak on her father's side and half English-Italian on her mother's side. She shares what it was like growing up in Kuching where she was first exposed to culture dances and the sape, as well as how she transitioned from a corporate consulting job to studying fine arts before eventually entering into the world music scene full time.

Alena's music and work is very closely tied to her heritage, where everything has a backstory and deeper meaning. The words spoken, the beads used and the outfits worn. Many of which are passed down from generation to generation. If you want to learn more about what it's like being part of Borneo's indigenous communities and how you can support world musicians like Alena, listen to find out.

Are you ready?

Let's go.

Hi, Alena. Thank you so much for joining me on this podcast today.

Alena Murang: Thanks for having me.

Ling Yah: So, we both grew up in Sarawak Kuching, but I get the sense that your childhood was very very different from mine. And I would love for you to share what your childhood was like from your memory growing up there.

Alena Murang: Oh, I love Kuching. It still is I think, a great place to grow up.

So a bit about my background, my father is Kelabit, which is one of the tribes in Sarawak. And my mother she's half English, half Italian, and she's an anthropologist and an English teacher. So they both met in Sarawak.

And I think with both their backgrounds, they gave my brother and I a really, really rich experience. As I was older, I realized that, Hey, like not every kid had a similar experience as I did. So for example, like at the weekends we would go to the beach, we would go hiking.

We would go to villages and my mum was doing research as well on old rituals, on basket weaving, she was in research on natural dyes. So we would spend weekends kind of delving into her research. I remember as a teenager, I got a bit frustrated because I wanted to just go to the cinema with my friends or go to McDonald's with my friends.

But no, I had to go for a hike for example, but now I, I love the jungle.

Ling Yah: Yeah. It was so funny when I was doing research and I read that you were going for hikes. I think you stayed in one of the longhouses to look for wild orangutans and it's so different from my own experience.

Was your mom actively encouraging you guys to do this? Did you feel as though you wanted to rebel greatly? Or was it, you just went with the flow cause it was very interesting?

Alena Murang: As kids we loved it. I mean, that was the life that we knew, right. going to look for wild orangutans was in Batang Air, but not in the resort area.

We stayed with the kampung people and back then as well. I remember my mom, She had a job to train the tour guides, how to speak English, and how to host tourists. So we would like to follow her along on those trips. But I think it was as a teenager, I just wanted to rebela a bit and hang with my friends at the weekend at the one or two malls that we had in Q2.

Ling Yah: Very few.

So were you very much in touch with your Kelabit side? I think some of them were living in longhouses as well, right? Still are as well.

Alena Murang: Yeah. So, our people actually come from Miri. So if you can picture Brunei on a map that's South of Brunei, right at the Malaysian Indonesian border, that's the Kelabit Highlands.

But my dad moved to Kuching, which is about an hour's flight from Miri. We had a lot of aunties and uncles and cousins that also lived in Kuching. So on the weekends, I think since I was six years old, my mom and the other aunties would send my cousins and I to dance class with one of the other aunties. So we would just. Spend the afternoon learning to dance together.

It all sounds very romantic, but actually like now we'll talk to the cousins that I was learning dance with. We're all like, Oh, I dreaded dance classes. Actually I just did it so I could hang out with my cousins.

But I mean, now we all know how to dance, so that's a plus and we really appreciate that now. But at the time it was like, Oh, I just want to run around with my cousins.

Ling Yah: That's so funny. But you guys loved hanging out with each other because later on you then the Safi together as well, like part of you were doing dance and part sape, how did that come about?

Alena Murang: Yeah. So I learned to dance when I was six and there were a bunch of us cousins, I think maybe around 15 to 20 cousins learned another dance, of different ages. When I was 11, I don't remember exactly when or how the conversation came about, but it was basically half of us decided that we wanted to play sape and the other half would dance.

So then by playing sape, we could change up the rhythm. We could be more creative with our choreography. And at that time there was only one CD album from Tusa Padang that we would dance to.

We didn't realize that oh, actually this is hardly anyone in our dad's generation that's playing.

We didn't do it to save the sape or anything. We just wanted to learn music.

Ling Yah: But why the sape? I think you were also learning the guitar and the saxophone, right? So did you not think of bringing different instruments to provide that kind of background for your dance?

Alena Murang: Oh no. We never thought about that actually. Yeah, I learned that guitar before I picked up the sape and I guess having that background in guitar really helps me pick up the sape that faster.

Ling Yah: Was it difficult to convince your teacher, I think it was like Matthew Ngau, to teach you? Because sape is something that was only introduced to females in your father's generation, right?

So it was quite new.

Alena Murang: Yes, Uncle Matthew he's Kenyah, which is one of the other tribes that is very close to ours. He married a lady just outside of Kuching. So he lived about 30 minutes outside of the city. And yeah, we approached him and said, Uncle will you teach us the sape? And only, I think maybe six years ago when I was playing a show with him and an interviewer came to ask us questions.

She asked a similar question to him and he said that after these young girls had approached him and asked if he would teach us the sape, apparently he went home and thought very hard about it because in previous times, so in the pre-Christian times it was taboo for women to even touch the sape.

And I think since the tribes and the communities became Christian, nobody really kind of questioned that taboo anymore.

He went back and asked himself if he should do that. What would the people say?

What would the community say? And he said to himself that nobody in that generation is playing. So he wants to teach us. So we were his first batch of students at that time. It was 2000.

Ling Yah: So maybe you could explain a little bit about the background to the sape, which I found very fascinating as I was preparing for this. Cause there are two types of sape, as I understand, right. The spirit sape and the human sape. So what you're saying is the human one.

Alena Murang: Yes. Sapa is a lute instrument from Malaysian Borneo, and also Indonesian Borneo and it's played by the orang ulu people.

And these are people that live really in the heart of Borneo, in the rainforest, in the headwaters of rivers and the sape, it's a stringed instrument made out of one piece of word and the back is hollow. And because it was an instrument used to be used in ritual healing. So there are two sapes.

The first one is sape bali. Bali means spirit. So the spirits up there and the other one is the human sape. And right in the past, it was only the sape bali and it was used for ritual healing. The legend goes that there was once a healer whose wife got very, very sick and he couldn't heal her then one day he fell asleep and he had a dream.

And in this dream, a woman told him to make this instrument. And once he's made that instrument and stringed it to play certain tunes and his wife would be healed. So that's what he did. When he woke up and his wife was healed. So ever since then, the sape was used for ritual healing to heal physical ailments and emotional elements and spiritual elements.

And then in the 1930s, Christianity started to come into our areas. And the tribes, most of them became evangelical Christians, Muslim Catholic, and therefore the pre-Christian rituals were no longer relevant. And that included the sape bali. At that time, the human sape was used more for entertaining.

So for dancing, playing folk songs. I mean, I'm not sure why the human sape also kind of died down in that period as well. So it's got a really interesting history to it. Now the sape is quite different from what it was before.

Ling Yah: Back then, the spirit sape and the human sape, what was it that was actually different physically?

Alena Murang: So there's not much that we know exactly about the spirits up there because the elders don't want to talk about it anymore. I have seen one It's different shape from the humans sape that is what we play today. It's a little bit more curved, like a vase shape and a smaller, longer neck.

And it has two frets carved out of the neck. So that means that you would have like three notes And it had two strings. Whereas the sape that we have today would have three or four strings. It would be pentatonic so at least five notes.

Ling Yah: It's so interesting that you said the elders don't want to talk about back then, the spirit sape. So the taboo is still there.

Alena Murang: The taboo is still there. I mean, we still have elders that lived through the pre-Christian times. And from what I understand, it was a very difficult time because there were spirits of the jungle and all kinds of spirits and all kinds of omens.

Like if they saw a certain bird flying a certain way across the path all activity had to be stopped or these other things, I'm not even sure if I'm allowed to mention.

I can tell you off air.

They just don't want to live those memories anymore and they don't want us to go and explore those memories anymore. There are a few things in journals that we can read.

So I do a lot of reading of academic journals also.

Ling Yah: That's so interesting. Why would they not want it to be shared? Is it because it's very sacred?

Alena Murang: I think for them, it's just for the very fact that it's against their current belief system. So it's not something that they want to bring to life anymore.

Ling Yah: So let's go back to the sape.

So you picked it up and you learned from uncle Matthew. Do you remember what your first lessons were like?

Alena Murang: I don't remember my first lesson but we would always have the lessons at one of the cousin's houses and there were informal lessons. They will organize them in a sense, like we had them every Saturday afternoon for such and such a fee.

But they could run on for two hours, three hours. We all have different abilities in the class. And obviously we were his first students as well. He still passed on the songs and the traditions to us via oral tradition. So we didn't have any writing. I remember back then also he had this like massive tape recorder, so he would record himself playing sape and make a tape for each of us to then go home and practice.

Yeah.

Ling Yah: That's really, really sweet.

Alena Murang: It is. It is really nice. I think that if I'm one of his tapes the other day, I was telling this to my first batch of students in about six years ago and they said, teacher, you do the same to us but it's just on WhatsApp. And I was like, Oh yeah,

It's a lot less laborious.

Yeah. Because as a musician, it boggles my mind that when you are learning an instrument, you don't have the actual notes. So that's something that was never a part of this learning, right?

No, never. And now also I do play with orchestras or modern contemporary bands, and I always say, I don't read notes, which is not true because I do read notes, right? I played guitar. I played saxophone. I did the exam and everything, but when it comes to sape, I cannot brain like putting the notes to the way I play sape. So I just say, send it to me. I'll listen and I'll play it.

Ling Yah: Did you find it very hard to master the sape, given that you had a guitar background, because the technique is quite different, right? I think you do the flicking. So it's a very different style.

Alena Murang: The technique is very different. I think I picked up quite fast. My cousin, Emma and I, we picked up faster than the others.

Emma also played guitar, but I think it's more, you understand how a string instrument works. Like for example, you play violin. So you would understand tuning ,you'd understand fretting in a way, like where to place your fingers.

Ling Yah: It has to be like very precise, has to be at that position at that angle, that pressure.

Alena Murang: Yeah.

Yeah. I said that it really helped. I mean, now I teach students with zero music background and I also have students that play guitar and they come and learn sape. And in some ways I feel like those with zero music background actually pick up the sape techniques better.

Ling Yah: So after that, do you have any thoughts in terms of what you were going to do with your life? Or is it just something that you were doing because your cousins were doing it as well?

Alena Murang: Yeah, I mean, growing up, we couldn't say we want it to be a professional sape player, like it wasn't a thing.

Ling Yah: Yeah.

Alena Murang: Uncle Matthew did it, but we also saw him like, yeah, but that's Uncle Matheu.

Ling Yah: The exception .

Alena Murang: There was no woman that did it. There was no young person that did it. So yeah, I never ever thought about it. I did have the Rainforest Festival as a kid. So I would always just look at the musicians on stage and in the workshops and be so in awe of them. And I remember telling my mom like, Oh, I want to be them.

So my mom actually took me to go and talk to some of the musicians and she said Alena, ask them about their lives. What they do. She said you'll see that they're not all full-time musicians, which is true. Like, I remember some of them were like pharmacists. I worked in an office, teachers and through the, and I was like, oh, okay. But I really didn't put much thought to it. I just thought it would be something that would be so awesome.

I wanted to be a vet. I wanted to be an interior designer. I want it to be in advertising. I want it to be a TV host. Like anything except for a professional sape player.

Ling Yah: How did you transition from all that to deciding to go to Manchester, to study business management? What was the thought process there?

Alena Murang: So after SPM, I went to the UK for A Levels and I really wanted to study art. I loved painting, but I wasn't pretty good at it. I just had the art classes at school, but because I arrived one term late in the UK because they start September and I arrived in January.

So I couldn't catch up on a portfolio for art. So I never did art. Anyway. I did economics. Math and something else. And then it came to applying to university and I still felt, oh I want to art. I really love painting and I just wasn't good enough to apply to the art schools in England.

My dad was like you're not applying to a school that requires three Es, Alena, you're not doing that. That's fair. so then I was like, Oh, what's like art? Advertising? I thought at the time, but also the advertising courses were like for the lower grades.

So then the advertising turned into marketing. So that's how I went to Manchester. I did marketing and management.

First year of university studied marketing, and I just didn't really roll with the ethics of marketing, right? Like the tricks of how to sell people things. It's just not my character.

So I dropped marketing and just did the full blown management course. So it's just a general management course. I was able to choose some interesting subjects. I remember I really enjoyed bridging the digital divide, so looking at rural areas and how to gain connectivity.

And I wrote my thesis on, exploring the social responsibility of logging firms in Borneo.

Ling Yah: Was identity something that you struggled with? I mean, for me, when I was growing up, I rarely saw anyone who was of an indigenous background, but you had Eurasian blood but also was indigenous.

So was that something you struggled with?

Alena Murang: Double minority. Yeah. It was something that I struggled with. I think because I was so rooted in my Kelabit heritage through music and through art, but at the same time I would be treated differently. Like I wasn't from Malaysia, right?

Until today, people are so shocked that I'm Malaysian. Even in Malaysia, I'm shocked that I'm Malaysia. They're like oh, where are you from? Like, oh I'm Malaysian, are you sure?

Are you sure?

And people are so shocked that I speak Bahasa and so, yeah, I still get that. So actually I was really looking forward to leaving Kuching.

I mean, number one, I think a lot of us were looking forward to leaving Kuching because it was a bit small.

But also I was looking forward to going to England because that's where part of my heritage is from, and I was like, ah, maybe finally, I can fit in over there.

But no, people in England thought I was Asian. I mean, I am, but they would call me Asian and wouldn't see me as British. Whereas people in Malaysia wouldn't see me as Malaysian. So, yeah, it was quite hard, like my late teens and early twenties, but I think at the end of the day I just found that I resonated with Malaysia or Sarawak most.

Ling Yah: So was that the reason why you decided to come back to Malaysia after you finished studies in the UK?

Alena Murang: Partially. So I got offered a job after university in KL ..I moved to KL for that job, and that was the first time I lived in KL. And I think you might resonate with me in that KL is another culture shock because it is completely different.

I mean, not completely, but there are a lot of differences.

Ling Yah: Totally different. I think what made it harder for me as opposed to when I moved to London, it was so easy. Coming to KL because people see me as Malaysian, they expect you to treat everything as normal, but it wasn't normal for me. I didn't know anything.

Alena Murang: It's like people see you as Malaysian, but you don't feel like you fit into the city because it's a totally different culture.

Ling Yah: Yeah. Let's go to mamak. What is a mamak? Like, you don't have a mamka. No, we don't. To this day. I still have people who don't believe that there's no mamak in Kuching.

Alena Murang: Yeah. So yeah, I moved to KL for a job in sustainability consulting. I also got put on other jobs like HR consulting or CSR consulting, but I just realized it wasn't really me.

Ling Yah: So after two years, how did you decide to move to Singapore and pursue an arts degree and not study?

Alena Murang: Oh gosh. That was such a hard decision to make.

Ling Yah: And your parents!

Alena Murang: I remember my parents came over to KL and we went to Kinokuniya - my family loved books - and we were in there for a long time, like an hour.

And I went missing, I was upstairs, above the cashier upstairs where all the art stuff are. So my mom and my brother came up and they found me and they're like Alena, we're ready to go. And I was carrying like this stack of art books, like in my hand, like this. And I looked at them. And I just started crying.

And my mom's like, why are you crying?

And I was saying I just love art so much. That was one of the moments.

but I didn't leave my job then. It was like maybe seven to eight months later. I had surgery underneath my foot. And I was at home for a month. I got some paint and I got a canvas and I just started painting again.

And honestly, like I wasn't a great painter. I just really enjoyed it. And it came to a point where I was like, Oh, I really want to paint this person since portrait, or I really want to paint something else, but I can't. Like I have it in my head. I can't technically do it. I just knew I wanted to learn. So yeah, it was after many months and I thought about it and thought about it.

And I thought if I leave my job now do a one-year course. If it doesn't go, well, I can go back into the workforce again. I'm still young. I didn't have any dependents luckily. So I did that.

Ling Yah: And what was the experience like doing art?

Alena Murang: It was great. I did a foundation course, so my course mates were fresh out of high school.

So 17, 16 years old. And I think I was about 23 at the time. I really got along well with them and we'd have great conversations. And what I loved about the course at LaSalle is that we did learn like technical drawing and stuff like that, but I learned more soft skills, like observation, reasoning, critical thinking, observing society.

Yeah, I learned all of those great things that I didn't learn at business school

Ling Yah: And did you feel that, okay, this is it. I want to be a fine artist.

Alena Murang: I guess not quite. I knew I wanted to paint. I mean, I still do. I love painting. Painting is really my first love. I saw that it would be really, really difficult, even just getting into the mind of an artist is so difficult.

It's a big journey to go on and if you ask me if it's something that I had dreamt off? Yeah. But it was a scary dream.

Ling Yah: Were your teachers encouraging you to go to this art field or to try something else?

Alena Murang: They weren't. I was so shocked.

Yeah, it was a foundation course. So with a foundation, you usually go into a degree diploma or I could have gotten into a master's for example. So I was really kind of stuck, like, what is my next move? I went to my lecturers, who I was very close with. They actually looked at my work.

They look at your journals, they look at your drawings and your lines and everything. And they said, Alena, if you look at all your work, like it points back to your roots, your heritage, Sarawak, and your elders. And I was like, yeah so. That's who I am. And they're like, yeah, but we never seen it. So like strong at someone in a foundation course.

And actually, they said to me as an artist, you have to be a very selfish person, but you are not selfish. You doing everything for your community, even when you journal about it, it's for your community. And I was like, huh, I really didn't understand. And they said, why don't you just do your thing?

In a year, we'll see what you want to do. I was like, ah, I'd already done a degree and these courses are not cheap so I was like, yeah. Okay. I don't want to just jump into anything that I'm not completely sure of. So I moved back to KL, not quite knowing what sort of.

Ling Yah: And so what was next? Once you came back to KL?

Alena Murang: Ahh. Two of my ex colleagues at the consulting firm, they actually were in a world music band.

I'd met them at the Rainforest Festival years ago, and then we somehow ended up in the same office by coincidence. So they were in a world music band.

Ling Yah: It was called Diplomats of Drum, right?

Alena Murang: Yeah. Diplomats of Drum. And they invited me on their US tour that year, like three, four months later. And at that time, actually, I didn't play sape.

My close friends in KL didn't really know that I played sape. It was at home. I just never thought about playing it in KL I guess. but they knew cause they'd seen me at the festival, so I said, yes. I practiced really hard. And we went to the US at the end of 2014, for four weeks and that was really, really fun.

And at the same time I had my dad asking me what's next, what's your plan that, and I was like, I don't know what my plan is, but just give me a while because I can feel this is the right thing. I feel so full and I feel so happy.

I had no idea. I didn't even expect to play the sape. I think that the US trip really opened my eyes to how interested people are in the sape of these stories that we have. Many people have seen, , an instrument from India or a stringed instrument from Africa, for example, but they've never seen the sape.

Some people never heard of Borneo, never even heard of Malaysia. singing is quite a recent thing. Maybe 2016, I started singing.

Ling Yah: So was there any particular incident that happened on that tour that stood out for you?

Alena Murang: So many in our set in Diplomats of Drum, as you can imagine by the band name, Diplomats of Drum, it's quite an upbeat band, right? And the song that I contribute the most to is Datin Julit Visa - it's one of our folk songs and it's with the band and kind of like the bass guitar and the drums.

It becomes quite an emotional song. A bit warlike, like very semangat. It was almost after every other show, someone from the audience would come and say how touched they were by that song. Some of them in tears. And I was like, wow, this music is really powerful.

So yeah, I think I just started seeing how touched people were and how much it impacted people, how much it impacted me as well.

And I just kind of kept slowly, very slowly going and gradually I started getting bigger gigs and bigger gigs in Malaysia. Yeah, I've been doing this full time since 2016.

So I got back from the tour. I remember I had quite a big art project, painting projects. I didn't push this up at all. Like, , I posted some pictures on Facebook and Instagram, but I had like 300 followers or something at the time.

I joined TFM because I did need a job.

TFM is Teach for Malaysia. and I still very much have a heart for education, because Teach for Malaysia, what they do is they reduce education inequality.

So providing access for all students in Malaysia to have a good quality education. And I always think that if my father and his generation didn't go to school and have the opportunities of education.,I wouldn't be where I am today. And a lot of my family still do not have access to education.

So it's something that's still very, very close to my heart. And I had management skills. So yeah, so I joined Teach for Malaysia as a supporting advisor. And really enjoyed it.

Ling Yah: And in the meanwhile, I think you also did this project with the Biji-Biji initiative in Genting?

Alena Murang: Yes. We had a painting project. That's the amazing project that I mentioned earlier. I was working for Teach for Malaysia in the week. And in the evenings or at the weekends, in my free time, I'd be painting. I had some commissions as well.

I used to really, really, really enjoy the open mics in KL, it was a really supportive community. There'd be open mics, you know, almost every night of the week.

Ling Yah: So you just go and play there.

Alena Murang: I would but I would play guitar.

Ling Yah: Oh.

Alena Murang: Yeah. I played guitar and I was singing a little bit. Like singer songwriter stuff.

And I remember like once in a while, I'd bring myself up there and it ended on the sape. I'd play three songs later and I would be like, oh, by the way, this is the sape. And start playing. I think it was from there that people started to listen to sape more.

And I think at that time in Malaysia with this whole like confusing 1Malaysia campaign people weren't really sure of like, hey, what is Sabah & Sarawak, actually? We don't really know much about them. So people were craving for these stories from East Malaysia.

The sape gave them an opportunity to listen to some of those stories.

Ling Yah: And around the same time, you also founded a social enterprise art for a studio, known as Kaned Studio. So how did that come about?

Alena Murang: Okay. Well, to be honest, I was given the name social enterprise. I was just doing my thing.

Okay.

There was a social enterprise wave at that time as well in Malaysia. I named it Art4 just to always remind myself to use art for a positive cause.

So it started with some disaster relief. So like, selling pink things or doing commissions to fund, like broken bridges or-

Ling Yah: I think that's at your kampung, right? You did a Facebook plea for it because the 3 bridges collapsed?

Alena Murang: Yeah. And even to this day, it's just the one bridge that is rebuilt. The other bridges still haven't been rebuilt, unfortunately. Yeah, supporting, mostly Penan kids through education.

Art4 Studio is kind of evolved across the years. And this year we renamed it to Kanid studio focusing more on production on art and music projects, basically anything that tells stories about heritage, anything that works towards making cultural heritage relevant, it's kind of very bespoke and ad hoc projects.

But we still do ad hoc, supporting kids through education, disaster relief and those kinds of things.

Ling Yah: Was it very hard for you to launch it, and run it, especially in the early days?

Alena Murang: Not really, cause I didn't put much pressure on it. It was something that was there. Again, it's grown very organically.

Even with my journey as a sape player, it's grown so organically as well. So it's not something that kind of put pressure on, had targets for.

For what I do as a musician or as an artist, the challenging thing is that I don't know, really have a model to follow.

I don't have exactly something, but he has done the same thing I can say, oh, these are the steps I need to take. So the way I make choices and decisions, I talk a lot with my family and my cousins, my uncles, my aunties, and says, this is what we want for our community. How should we do it? How should we put it?

You know, what's the next project we should do? Yeah, stuff like that. It's very organic.

Ling Yah: And it was very brave as well because within one year you decided to enter into music full-time in 2016. Was there a tipping point where you decided I'm ready to enter into music and give it go?

Alena Murang: It was just that I was getting a lot of gigs and at the same time, my Teach for Malaysia contract was coming to an end.

So it would either be renewed or finished lah. I was getting enough shows and enough gigs. And I had students at that time also. So financially I felt like I could sustain myself.

Ling Yah: How was the conversation with your family when you told them that this is what I want to do?

Alena Murang: My parents, they've always been supportive, right. Because they are the ones that sent me for lessons in the first place.

Ling Yah: You asked for it.

Alena Murang: Back in the day, yeah, they have to be supportive. But I think again, it's because it's not just a thing of like, Oh, how did she make a living out of art and music. But it's also the thing I'd like her to make a living out of playing sape.

Ling Yah: Yeah.

Alena Murang: So they were always supportive, but I think nervous and worried for me. I think we really, probably only up until last year So I think it's also that I've lived away from them for so long that they don't see the everyday things that I do.

And as well in KLit's so different from Kuching and they don't see the media industry, they don't see the entertainment industry here. So I think they were very nervous and very worried.

Ling Yah: So what was the plan? Did you have one because you released your EP in the same year as well. So was that something that you knew you were going to do?

Alena Murang: No.

When I say this is a very organic journey, it's very organic, right? So back in 2006, we had a cousin band called Kanid that played at Rainforest Music Festival. So that's when I met my cousin, Josh.

He came in from KL to be the drummer, right. And after that, Josh went off to Berkeley to study music. So around 2016, he came back to KL. We met up.

I remember having drinks with him. And he just said, I want to produce you. I know. And I was like, what does that mean?

Then he broke it down for me. And I was like, Oh, maybe I'm not sure. When we would meet up, he would tell me I guess, I want to produce you. So eventually I said, okay, Josh, how much money do we need? Like, what do I need to do? What songs do I, all this kind of stuff.

And then, yeah, I just muddled along with it. And then I had an album.

Ling Yah: So do you mind sharing, the thought process? What you just said: how much you need, how do you come up with an EP? What was that like?

Alena Murang: The songs that I have been playing that were put inside the EP, I've known them since 2000.

So I've known them for 16 years. So it's not like I didn't have songs. We just mapped out the songs and I kind of really just trusted him and his vision to develop those songs,

I remember though there was in the song, Lilin, he did do a demo with a drum kit in, and I was like, nah, I want this to be more traditional, something that can become a reference.

He was like oh, okay. And then we went into the studio and released it. I did an EP launch at timber, this live venue, and it was so full. It was so full. I didn't realize how full it would be.

Ling Yah: Wow. Were you involved in the marketing?

Alena Murang: I was. I was hands on with everything. I was hands-on with everything. I guess sometimes you send out invites and people don't really RSVP.

I was really overwhelmed.

Ling Yah: And what happened after that? I think you were going off on all these world festivals?

Alena Murang: Yeah. So I remember that time, I had two friends who were doing life coaching. They're older than me and wiser than me. So I started life coaching with both of them. One of them is more focused on my emotional wellbeing and the other life coach.

She's more focused on that business and goal settings.

So with a life coach, right, they kind of sit you down and ask you hard questions that only you can answer and they give you the tools to answer it. But again, only you can answer and they ask very specific questions if you cannot answer.

I remember one of my answers to their questions, I want to travel and I want to play music.

And she said, write that down, write that down. So I wrote it down. I have a paper somewhere and yeah, ever since then I been traveling. overseas to like festivals, small festivals. I was actually very thankful because I was getting very tired of traveling, not tired of traveling.

Actually. I was getting very tired, very exhausted in general. But sometimes I look back and I'm like, I don't know what it is like, thoughts or desire or intention is a very powerful thing. I mean, honestly, I cannot brain like being this kid at rainforest festival, just wishing I could be this musician on stage.

I didn't sing, I didn't play anything professionally. I didn't go to music school. And suddenly, like, I can be playing at festivals in random places across the world. Really. I think I've been reflecting on that a lot this year and just thinking like, wow, how did all that happen?

Ling Yah: Were you ever plagued with imposter syndrome asking yourself why me? Why here?

Alena Murang: No. I think I was always very certain that this is my path. Not to say my path is to be a professional sape player, traveling the world and all this stuff, but my path is to be somebody that carries our heritage . Right now, or maybe in the last five years, the way of doing it was to play music and to play at these festivals overseas.

I don't know if the next five years, it would still be in a different way. But I think I just have to stay very clear headed to be sure of what I'm doing.

Ling Yah: When were you certain of that path? Was there a moment where you went, I am doing what I'm meant to be doing?

Alena Murang: I don't remember that exact moment, but I guess that moment quite often when I'm on stage at a festival.

I play all kinds of stages, right. So I don't really get that feeling when I'm on a corporate stage. I get that feeling more when I'm on a stage where I can be completely who I want to be, whereas I can direct the show as much as I want to direct.

So if it's my own production or at a festival or I have even had those moments playing in front of like 30 people in a community hall, for example, I think it's when I see how people react to the music, how people react to the stories. that's what I know, that's what I should be doing.

Ling Yah: So I noticed as well that you went to so many different festivals, like Norway Fjord festival, which is the largest Scandinavian traditional music festival. And you also were at like Paris fashion week.

So how did all these really different opportunities come about?

Alena Murang: So Paris fashion week was actually with Stylo. Stylo is a Malaysian-based fashion agency. It was with a group of Malaysians in the fashion industry that were debuting in Paris. So one of the brands invited me to play for their catwalk live and it was very nice.

It was on a boat on the river and the background was the sparkling Eiffel tower. It was very nice. And then I organized some radio shows. So I played sape on their radio in Paris. And after that, we went to Rotterdam and I had a show there, and then I flew home. That's nice. That was one of my earlier trips, actually 2016 or 2017.

Fjord festival in Norway, that's actually a very big festival in my industry.

So my genre of music is called world music and it has a very, very different industry as compared to rock music, pop music, classical music. So the world music industry or the network is actually quite small.

And we have like specific types of marketing, specific types of managers, agents, festivals, labels. Yeah, so Fjord Festival is one of the top of the list. So it was really, really great to be there. It's like in this small village in Norway, in the fjords, yeah. That was actually quite a moment as well.

Not necessarily being on the stage at that festival, but we were also shooting a documentary at the same time and I sat by the river and played sape and I just felt like, Oh, I don't even know how to describe the feeling.

I felt like I had come one big circle sitting there by a river. I mean, usually I would be playing by another river in Borneo and by the river, in the fjords in Norway

It was like, what am I doing here?

Ling Yah: Do you feel like you had to be overseas in order to promote your own culture and music? Because I feel, at least from what I can observe, that world music, at least in this part of the world isn't as appreciated as maybe overseas, do you feel?

Alena Murang: There's a very weak world music industry in Southeast Asia.

For world music, you need very specific managers, agents, labels, da da da. And I haven't been able to find one that suits me. And actually when I was starting out on kind of being a professional sape player, a very prominent lady in the arts in KL told me, get out of Malaysia.

Yeah. I was so shocked because she just said, get out of Malaysia, make your music sexy outside of Malaysia. Only then Malaysians will listen.

Yeah.

Ling Yah: You didn't resonate with that.

Alena Murang: That's true. I didn't really understand what she was saying. I was like, oh, I can understand that, but I'm not sure if I believe it. That's not the reason why I went overseas. I mean, the reason why I want to play overseas is to expand the reach of our music and our stories.

But I think having that overseas experience kind of, I guess, draw attention to me back home as well.

Ling Yah: So you did not feel the urge to stay overseas?

Alena Murang: Sometimes I think that if I was based in Amsterdam or Berlin or London, those are the world music arts. I could grow a lot faster, but then I think about it as well.

I've lived away from home for so long and lived in different countries and. I always ended up missing home and my music and my stories are so closely rooted to home. To Sarawak that I think that would just be too hard for me to be away.

Ling Yah: I think what's really magical about your music videos as well, is that you really involve your family in it. Like they would be singing in, or dancing in it. So that's really special, that you would go to them and make them a part of your music.

Alena Murang: It is, it is really special. I mean, we released Midang-Midang last year.

Ling Yah: I loved that song.

Alena Murang: Thank you. And yeah, I worked very closely with my cousin, Sarah. She directed the music video and she styled it. She choreographed it. And for that music video in particular, we wanted to make sure that every film department was led by orang ulu youth. So even hair and makeup was by Gabriel Padan, he's orang ulu as well. And then the dancers but as well, like we love working with people who are not family and not Sarawak.

Okay. So I don't want to say, I don't want to seem like I'm so exclusive.

I really don't. But I find that my cousins have the same lived experiences as me. they had the same challenges. We are the first generation to be born outside of the rainforest. So we have parents that were born in the rain forest and lived their life in the rain forest and like walked 10 days in the rainforest to get to school and so growing up, we hear their stories and we have the same community values that they have.

At the same time, like we're city kids. Working with my cousins, we kind of understand the viewpoints. We have the same lived experiences and we're on the same page in terms of what we want to share and what we want to talk about.

And the synergy is just amazing. And it's so easy.

Ling Yah: Is it a challenge to get the elderly part of your family, like your tepu to get involved in it because it must be something that is so bizarre, at least at the start, right?

Alena Murang: I love our elders so much.

I went through a phase of painting elders because I just loved it. Have you seen them? Yeah, I have, I mean, I love just the faces have so many lines and so much texture, like in that way I love painting them, but also I just love meditating on their story and they've seen so much transition in their lives.

They lived through like, pre-Christian times they've lived through having roads enter the village. They've seen the missionaries come, they've seen schools enter, they've seen money enter, oh gosh. they've seen electricity enter and phones.

Like, they have lived through so much transition and change. I'm always so in all of them. So I think when, like you have these city kids coming back to the kampung. it's nothing big.

But I think think they find us a little bit of amusing. Like, yeah. We shot Midang-Midang music video in Bario, right in the village and half of the tepus, the grandmothers, they didn't know who I was because I was wearing so much makeup, right.

Ling Yah: Oh

Alena Murang: Yeah. They didn't recognize me until I spoke to them. And I said, do you know who I am? They're like, why are your eyes so red? Why are you sitting in a pond?

Ling Yah: What was it like being a part of Small Island Big Song, because I think you brought the production team to your village as well, right? And they went and visited all kinds of people.

Alena Murang: Yeah. Small Island Big Song is a project started by Tim and Bao Bao and they're telling the story of Austronesian heritage through music. So Austronesian heritage is, I think more accurately it's a language group. So it involves the indigenous of Taiwan, Malaysia, Madagascar, Polynesia, Hawaii, Tahiti is an Island.

And a lot of the Polynesian islands and many of these groups, the theory is that we originated from Taiwan. And actually we are the biggest language group in the world, but not many people know that. I didn't even know about this Austronesian connection.

Like. Even my band mate in Easter Island, he didn't know about it. So it's been so amazing getting to know my band mates and sometimes we speak our own languages and we're like, you say that too? We use the same word. And then we're always like, oh, family. And, It's just, I dunno, it's like finding a long lost family, really. So yeah, Tim and Baobao went to each of our kampungs and they came to mine, mine was one of their last stops, actually.

So I played some songs for them. And then what their process is also is that they had, like the head of tune from an artist in Easter Island, which they brought to Madagascar. The artist from Madagascar played over that song. And then they brought it to Indonesia. They had some drummers play over that song.

And then they brought it to me. And I added into that song, it was like this musical family, I guess. Actually a lot of my bigger tours were with that production.

Ling Yah: And it won Britain's Songlines music awards. Right.

Alena Murang: Which is like, yeah, that was amazing.

Ling Yah: And I would love to talk about, so this is one thing that people asked me to ask you, which is the beats, which is very important to you and it's always shown, right.

Could you share with us why beads are sowing integral to you in your culture?

Alena Murang: Yeah. So beads were actually brought through trade. We didn't make beads and these beads came through trade. A lot of them originate from Italy, Czech Republic, Africa, India, China. Every bead has a name and the ladies and the aunties, they know where they came from. They know the name of the bead. They know the value of the bead and you'd have these certain, dark blue beats, like one beat could be worth a Buffalo.

And we have our traditional beaded skullcap called Kata. And the old, old ones can fetch a lot of money. They're really valuable basically. So they were used as money could be used to trade items, trade food, and the beat lukut could be traded for a human life. So for example, if you wanted to save someone or if you wanted to buy someone as a slave, you would use that one bead the lukut. But why is it so important?

In the past, the very essence of being was to gain lanut, to gain a spiritual height. And how a man would gain that spiritual height is to do that very well in hunting and to be very skilled in head hunting and in warfare, right. So that's feeding your family and protecting your community.

Whilst the women, they would have to be very skilled in planting rice and harvesting rice and owning beads and stringing beads. So the men and women had their very clear roles and we can see that beads were very important from way back. But I think like symbolically it showed that you were well off and you could provide and protect the community basically in the past. Nowadays they are still important, but I think that's more for tradition and culture.

Ling Yah: And I think that's something that you are very conscious to incorporate in your costume as well, right? When you go on stage.

Alena Murang: Everything has a story behind it. Like my costumes, the beads that I wear. If you see a music video as well like, everything has a story.

Ling Yah: Since we are recording this in 2020, I wonder how has COVID impacted you and what you're doing?

Alena Murang: I haven't been traveling.

In February my band and I went to Taiwan, we played a festival there and then in end of Feb and March , I was in Panama for a festival. So I got my travel in. And if it wasn't for my best friend's wedding in March, which I left the festival early to come back for, I'd probably still be stuck in Panama.

So my mom's like, ah, you have to like really. Thank Lillian for her wedding.

It's weird. Honestly, it's been a very weird year. I mean, I'm very thankful that I've been fine. My family has been fine in all ways. So when lockdown happened, I was actually really looking forward to having downtime. I hadn't had downtime since July the year before. So I was really looking forward to that.

I was actually already booked to work part time on a management consulting project related to Sarawak for this year. So that set me up quite well. And to be honest, like I've had quite a few online gigs, virtual events. I had one or two proper events with the audience.

I'm actually really busy actually, It was strange. I mean, one of those shows was at Damansara Performing Arts Center. There had to be two empty seats in between each person. So yeah, it was sold out. But you know, when you look at the audience, it's like, one fed fall. And-

But honestly like, the precious applause from a live audience, we were like, oh, that sound.

Ling Yah: And where do you think the future is going to be for you?

Alena Murang: Oh it's so hard to plan.

So now I'm really focused on completing my album, which I actually started two years ago.

I'm really excited to share it with you guys. Cause it's a new sound and we have a lot of influence from, blues, from rock, from new metal, from pop. And I'm not sure, people say that full blown festivals probably won't be back until 2023.

I don't know. Who knows. I mean, I think let's say full blown festivals, like ones where you can travel overseas but I think in Malaysia, we will be having some festivals. I know Borneo Jazz and Rainforest Festival are being planned for next year. I think I'm going to spend more time also, doing research and documenting more songs and learning.

Ling Yah: And is there anything that anyone listening now could help you to make your life better?

Alena Murang: Ah, let me get my list. I say that there's three free ways that you can help an artist, especially in these Corona times. The first one is just sharing their content, on your social media, on your WhatsApp, just show their content. Listen to their songs on Spotify, iTunes.

Like their Instagram posts. You like their Instagram posts, but the algorithms keep changing so now you have to save a post instead of liking it. And commenting. Actually social media, these likes, and you know even the YouTube likes and stuff that they do mean a lot for us.

yeah. And they do translate into funds as well. And it's a free thing for you guys to do.

Ling Yah: Is there anything that you believe in that you feel not many people do?

Alena Murang: I mean I don't know if most people don't believe in this, but I really believe in the power of intuition and feeling what is the right path for you.

It's quite hard to rationalize. And I think not many people are as lucky as I am in the sense that they know what they want to do. Some people know what they want to do, but circumstance means that they can't do it. But I think, if you really kind of dig deep and shut out the noise, you can really find what it is that you want to do and what you were born to do.

And honestly, it seems scary to take the first step, to make a change, to do what you want to do in your life. But if you feel like it's the right thing, just do it. Just take it step by step and just be very aware of your journey and decisions that you have to make. They will become clear to you.

It's complete like faith, that's it . Faith in your journey of faith in whatever it is you want to believe in.

The journey that I'm on is very beautiful, but it's very, very hard and it's hard to make decisions sometimes, and it's hard to know what is the right thing to do, but you just have to kind of trust your gut and listen and see the signs and go with it.

Ling Yah: Well, Alena, thank you so much for your time. I normally end all of my interviews with these questions. So the first one is, have you found your why?

Alena Murang: Yes, I have found my why.

Honestly, this one's very hard to define because it's very wishy washy. and I always say I make myself a vessel for my community and my heritage and my culture and why I'm doing it is because that's what I'm meant to do.

Ling Yah: What kind of legacy do you want to leave behind?

Alena Murang: In terms of tangible things, I wouldn't leave behind this whole, like a huge bucket of songs in native languages. Songs and their excellent visuals and like artwork.

That's what I want to leave behind, I know I want future generations doesn't matter what race you are, what ethnicity you are to enjoy them and to use them as a reference.

Ling Yah: Is there anyone in particular in this world that has done it really well, that you want to follow?

Alena Murang: Yes, there are. One of the artists that I really look up to is Fatoumata Diawara.

She's a Malian singer and Calypso Rose. Oh my gosh. I shared a taxi with Calypso Rose from the festival to the airport. In Czech Republic, she is such a queen. She's about 80 or 90. She's the queen of Calypso music. And she competed with revived Calypso music.

Ling Yah: And what do you think are the most important qualities a president should have to succeed in your field?

Alena Murang: you need hard work and you need to have a lot of grit. So just keep moving forward. There's going to be a lot of failures. There's going to be a lot of challenges.

So having grit and with that also, staying focused and also just to be smart. Educate yourself in law in business. I think those are really important assets for an artist or a musician.

Ling Yah: Where can people go to find you and support what you're doing?

Alena Murang: I'm on Instagram a lot, so that's Alena Murang on Instagram.

And my website as well: alenamurang.com and on Facebook.

Ling Yah: And I will add all the links to that in the show notes. Thank you so much, Alena, for your time.

Alena Murang: Thank you.

Ling Yah: And that was the end of episode 22. The show notes can be found at www.sothisismywhy.com/22, which includes a transcript and links to everything we just talked about.

If you want to hang out, we also have a private Facebook group to keep the conversation going. And some of the previous podcast guests will be showing up for a limited time to answer any of your burning questions. To join, just head over to Facebook and look for so this is my why.

And stay tuned for episode 23, which drops next Sunday because we'll be meeting an incredible Malaysian female co-founder of a global consortium of over VC funds that have pledged over 1 billion US dollars to help female-founded companies.

Her two passions, female empowerment and VCs, and her inspiring story is one I can't wait to share with you next Sunday.

See you then.