Powered by RedCircle

Listen at: Spotify | Apple Podcast | YouTube | Stitcher | RadioPublic

Welcome to Episode 120!

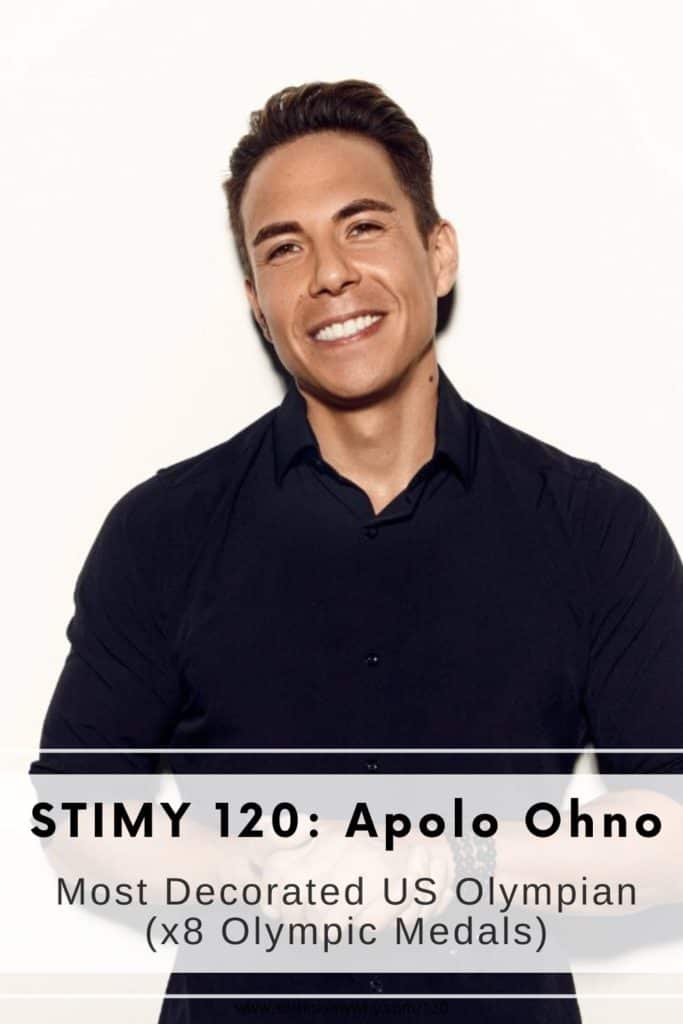

STIMY Episode 120 features Apolo Ohno.

Apolo Ohno has won 8 Olympic medals & 21 World Championship medals, which makes him the most decorated US Winter Olympian in history!

He was the state champion swimmer at age 13 & national speed skating champion at age 14, but it was short track speed skating that really caught his eye.

Because to him, they were like Superman!

After 6 months of training, Apolo won the 1997 US Championships. He was a shoo-in for the 1998 Winter Olympics but then…

Apolo grew complacent.

He self-sabotaged & threw away his training, finishing last in the Olympics trials.

His father was so upset, he sent Apolo to an isolated cabin at Copalis Beach and said: “You’ll stay here for as long as it takes for you to figure out what you want to do with your life!”

That was traumatic.

Apolo decided he would give this sport a real shot & that’s when everything changed.

But there was a price to pay for such “psychotic obsession”.

He was ruthless to everyone, including himself.

In this STIMY Episode, we talked about how he finds FLOW, sports psychology, self-sabotage, the importance of recovery, and being obsessive without being “mindlessly handcuffed to it”.

So if you want to live your life to the fullest the way an Olympic champion does, then this is the episode for you!

Don’t forget to watch on YouTube.

PS:

Want to be the first to get the behind-the-scenes at STIMY & also the hacks that inspiring people use to create success on their terms?

Don’t miss the next post by signing up for STIMY’s weekly newsletter below!

Who is Apolo Ohno?

Apolo Ohno shares what it was like being raised by his father, who was a Japanese immigrant and single father, and what his father taught him about sacrifice.

Including waking up at 3.30am every day to practice skating in a freezing cold carpark!

- 3:27 Survival

- 7:23 Why did this happen?

- 10:35 Blowing up toilets?!

Psychotic Obsession over Short Track Speed Skating

You don’t get to Apolo’s level without some form of psychotic obsession, but it comes with a price.

- 12:25 Joining the Superman sports

- 15:33 Sleeping with his skates

- 16:48 Sacrifice

- 22:01 Not being handcuffed to failure

- 24:39 Self-sabotage

- 30:57 The darker side to obsession

- 39:31 Finding the FLOW state

- 42:50 The power of introspection

- 45:25 The controversial Salt Lake City Olympics win

- 49:20 Turin Olympics

- 50:46 Why Apolo turned away from Hollywood

- 52:30 A lion is most dangerous when it knows it’s near its end

- 56:11 Psychotic obsession outside of sports

The Great Divorce

Unlike most careers, an athlete’s career ends in a few short decades.

This happened to Apolo, who described that period as the Great Divorce.

He shares what that period was like, and how he applied the lessons and discipline he cultivated as an Olympian into life post-Olympics.

- 57:31 Not returning to sports + Michael Phelps

- 58:51 The Great Divorce

- 1:02:37 What do you say yes to?

- 1:05:07 Building his personal board of directors

- 1:08:31 Who are you? Who are you? Who are you?

If you’re looking for more inspirational stories, check out:

- Barney Frank: Former US Congressman, Chairman of the US Financial Committee and co-lead sponsor of the Dodd-Frank Act

- Lydia Fenet: Top Christie’s Ambassador who raised over $1 billion for non-profits alongside Elton John, Matt Damon, Uma Thurma etc.

- Eric Sim: From being the son of a prawn noodle hawker stall owner to the former Managing Director of UBS with 2.9 million LinkedIn followers

- Adrian Tan: President of Singapore’s Law Society & the King of Singapore

If you enjoyed this episode, you can:

Leave a Review

If you enjoy listening to the podcast, we’d love for you to leave a review on iTunes / Apple Podcasts. The link works even if you aren’t on an iPhone.

Patreon

If you’d like to support STIMY as a patron, you can visit STIMY’s Patreon page here.

External Links

Some of the things we talked about in this STIMY Episode can be found below:

- Apolo Ohno: Website, Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn

- Subscribe to the STIMY Podcast for alerts on future episodes at Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Stitcher & RadioPublic

- Leave a review on what you thought of this episode HERE or the comment section of this post below

- Want to be a part of our exclusive private Facebook group & chat with our previous STIMY episode guests? CLICK HERE.

STIMY Ep 120: 40 Secs to Win & The Power of Psychotic Obsession | Apolo Ohno (Most Decorated US Winter Olympian with 8 Olympic Medals & 21 World Championship Medals)

===

Apolo Ohno: So sports psychology 1 0 1 is be very mindful of what you say to yourself because you are always listening, okay? So the way that you communicate with yourself that no one else can hear, be very cognizant of what you are actually saying, because over time, your body in your mind will accept those things as truth.

That continued for up my entire career, but I became more mindful of what I was saying to myself. So the change was rooted in this idea that if I was able to use the fear of failure simply as a means of making sure that I stayed obsessed, committed and consistent, that was gonna be my superpower.

Because I feel like genetically there was better athletes out there, but this right here was the game changer. This. Was the single greatest tool that I felt had all the studies that I was doing from sports psychology, from watching my teammates, from seeing the other athletes. No one was training this, no one was using this in the way that I would read these like fairy tales of like monks training somewhere.

And maybe they're true. I, I don't know. But I wanted to believe those things. So the power of belief and faith in your own ability is immeasurable.

Ling Yah: Hi STIMIES!

Welcome to episode 120 of the So This Is My Why podcast. I'm your host and producer, Ling Yah, and today's guest is Apolo Ohno.

Now Apolo is the most decorated US Olympian at the Winter Olympics, having won eight Olympic medals and 21 World Championship medals and was inducted into the US Olympic Hall of Fame in 2019.

Since going through the great divorce where he left his sport, he has become a successful entrepreneur, sports broadcaster, TV personality, and author with the New York Times bestselling book zero Regrets. As you can probably guess, such such success didn't come without the price.

And in this episode we talk about how Apolo's Japanese father would bring him out to practice skating in an empty carpark at 4:00 AM and how he developed his psychotic obsession race sport where he wouldn't even eat an almond or less to become an athlete, perfectly primed for his sport. We also talk about the dark side of such obsession and also how he's redirected his focus and life since deciding to leave the sport.

As well as how these principles can apply to everyone, regardless of whether you're an athlete or not.

So if you're someone who is ambitious and wants to live life to the full, then this is the opposite for you.

So are you ready?

Let's go.

Your father, basically a single parent, your, your best friend, your mentor, your coach, your dad, and he had this mentality as an immigrant of survival, then thrive.

I wonder what that was like with a father like that

Apolo Ohno: Yeah. And, I'm so glad that we could finally do this. Just was, you know, off camera was obviously giving you all the kudos and respect and adoration for your consistency and commitment to the show.

I think that that's an amazing lesson for all of us in whatever craft that we're pursuing. But to answer your question You know, my father Japanese immigrant came to the US when he was about 17 years old. He didn't speak the language, didn't have any kind of money or career path or understanding of how to integrate into the Americana culture and society.

And it was a real struggle for him. So when I say the words like it was first about survival and then eventually how to thrive, my father didn't. He didn't know what really he was intentionally trying to be here to do. Like there was no purpose. He just knew that he sought a different life outside of Japan without knowing anybody, without really understanding the cultural norms and behaviors and what was being accepted at the time, especially post World War II was a really unique perspective for him.

So he had to survive and, and survival to my father meant he just needed to do and create any opportunity from a job perspective in order so that he could actually eat. Whether it was washing dishes, driving semi trucks, becoming a bartender, which by the way, like. Imagine like a very short Japanese man with a very thick Japanese accent who doesn't know how to make you cocktails or drinks.

You come to the bar and this guy's like trying to figure out what you're actually ordering. I mean, I can only imagine the type of like microtrauma that occurred for my dad during that time, but he had this willpower within him that was really unique and especially when I was born.

That's what changed everything. I think that, you know, he had big aspirations to be in like the fashion and hair industry. My father owns his own still to this day, 42 years in the same location, the same business that he has operated out of. Yuki's diffusion in downtown Seattle, where he cuts people's hair and most of his clients that he's seen them for like 30 plus years.

So some of these people don't have hair anymore and they still come and they sit in a chair and he's giving like scout massages, right? Because he is become effectively the local community therapist and psychologists, you know, albeit unlicensed. So he has just shown an incredible tenacity of work ethic combined with purpose.

And his version of thriving today is about his physical health, his mental health, and I think his sense and overall direction of purpose. The survival side is still very much a part of who he is and who he was. And even when I talk to him, he still uses the word survival in our conversations. And it's quite strange, like in 2023, many people, unless you are in a very peculiar situation but if you live like in the United States, like your survival, like you can always probably get most of the time food, you have shelter.

So he doesn't live in those kind of dire circumstances. He's got everything that he needs, but he still uses the word survival. So I glean from that this incredible psychological edge that I see relevant in and prominent in many other people who have reached very high levels of success in their own careers is there's this survival instinct that they continuously keep pushing forward.

It goes beyond trying to make more money or trying to become more successful. It's this inner desire to just show up fully on a daily basis and create a consistency of habit and routine that I think is tied to responsibility and purpose. And as I grow, you know, I'm 40 years old now turning, you know, turning 41 and, and, May 22nd.

I think introspectively quite often about my father's journey. And then what can I learn from that as a 41 year old going on the age of 30, like psychologically? And, and I can go into that later why I think that, but yeah, my father's survival and thrive is, is really interesting.

Ling Yah: I mean, clearly that awareness was probably not something you were aware of growing up when you were six, when you were seven.

So your relationship, the way you saw your father was probably very different as well. I wonder, did you feel as though that kind of survival instinct sort of filtered down into you and that sort of impacted the way that you saw and did life when you was your child?

Apolo Ohno: I think it comes back to the way that my father had decided to raise me, felt a bit different than the other peers and, classmates that I had.

The way that my father communicated to me, for example, was always in this positive, supportive, unlimited, in potential vocabulary. So the conversation was, typically, and this was in sports and in academics. So if I didn't perform very well in sport or in in school, he would basically question and then create questions for me to answer.

Like, I would have to ask a question, well, why do you think that happened? What do you think went wrong? Where did you feel like you went lost? Or what could you change for the next time around? And this began very early. I don't know if it was intentional, but I believe that a part of my, dad's Japanese philosophy mixed with like the Americana side, that he was, blending, was that anything is possible.

And he drilled that into my head at a really young age. But it was also mixed with this fanatical work ethic. today. I don't think many parents are probably doing that for their kids to push them in the same way. I mean, you know, you hear the term like Tiger, father Tiger Mother. My dad was all of those things all the time, and he just felt like the more that he could push me, the more that I would adapt to those really stressful situations and environments.

And looking back, he was a hundred percent accurate and right. And so that became a strength of mine was the ability to adapt into a massive, overwhelming amount of stress and capacity and volume. Whether it was workload and training for the Olympics, whether it was academics, whether it was being thrown into a circumstance of like having to learn on the fly.

These are skillset sets that became hard coded into my brain as I grew older. So my father just had huge expectations, but also belief that I could be anything that I wanted to be and I could be spectacular. Now, a lot of times my father believed in me before I even knew what that actually meant.

So this took a lot of pushing and prodding and pulling me to guide me into whatever he thought was was going to help me grow.

And that was like where there was like Northwest Boys choir acting all different types of traditional American stick and ball sports, and then eventually falling into swimming roller skating. And then finally short track speed skating, which I don't know if a lot of your listeners even know what that sport is.

We race on the inside of an ice hockey rink. The same rink that figure skating athletes skate on during the Olympics. There's pads on the outside barrier, and then we skate and we compete against other athletes and these like very closed quarters. So I fell in love with that sport, and it sport had saved me in so many ways because it taught me how to harness this ADHD brain that I was developing as a child.

And it helped me harness and focus in on something that I deemed to be really important in my life. And it all came from my father in the way that he raised me.

Ling Yah: Before we dive into this Superman sport that you are talking about, I imagine for anyone, pretty much anyone I've met who has a tiger mom, tiger Dad, tiger parent.

You as a child would generally push back and go, no, this is not what I want as a child, right. And I learned that when you were in early teens, you got involved. Your dad got a call saying that someone had blown up the toilet. I wonder if you could share a bit about that period before you got on track.

Apolo Ohno: I mean, look, in junior high, kids were really mischievous.

They were bored in class, I mean, I chalked this up to like, failed like school system that just wasn't engaging enough to keep these kids entertained. Cuz if it was, they wouldn't be thinking about blowing up things in school. Right. Like, I mean, and who does that anyway?

That's insane. It's a crazy I wasn't the one doing it, but there was people in school.

I mean, there was just like fights every day. Conflict, chaos, drama, you know, typical. High school and junior high school stuff, and, but I think my father just noticed that there was the potentiality that existed that had I been around the wrong people and the wrong peer group, that that would, I wouldn't say drag me down, but it would steer me in a direction that was vastly different than what he had articulated to me.

What was the possibility of my life and how that could be, but I didn't, I mean, you're 13, 14, 15 years old. You don't know what any of those things are that I just told you. All you know is that here's a peer group that accepts you, whether it's good or bad, you feel like they like you, and so you naturally are drawn to this community of young.

And that's exactly what was happening when I was younger was that you know, I think we know what's right and wrong when we're younger, but at the, at the reality, like we're so, you know, it's such a pro-social environment, especially in those days of when I was growing up in school that you just kind of go in whatever direction you feel like you're the most accepted in and that you, you feel catered to.

And that's exactly what happened to me. So my dad saw that and he was like, this is not gonna happen to my son. We need to find a solution for him immediately. And sport happened to be that solution.

Ling Yah: You said before that your dad wanted you to be a state swimmer, but then you end up doing short track speed skating, which he called a Superman sport.

I wonder what that transition was like. Why was it that you felt so drawn to this out all the many different things that you were.

Apolo Ohno: Well, I, I began swimming and I was, I actually was excelling at swimming at a very young age. I was a state champion swimmer in Washington state. We had broken some, like, I guess some very old records that had stood the test of time in Washington, like 20 year old records.

And I didn't really know. I was quite young. But then my father saw this unique sport of short track speed skating with me many, many years ago, and it was my first introduction into the world of short track speed skating. And we called Superman sport because if you rip the cape off and just Superman is wearing his like spandex outfit for like aerodynamics, that's what these athletes looked like to me when I was like, you know, 11, 12, 13 years old.

They're like racing around this ice rink, leaning at these impossible angles. It was a beautiful feat. And then when I went to go see it live in Vancouver, bc, which is only two and a half hours north of where we lived in Seattle, that was the game changer. When I saw it live was when I fell in love with the sport.

I was like, I want to do what they're doing. But the transition was Paul's excellent swimming, but this sport of speed skating, he has such a raw, natural talent for it. And when I learned how to speed skate, I was, I picked it up very quickly and my father said, well, the next Olympic games that Apollo could potentially compete in would be the Nagano Olympic Games.

This is a long time ago, 1998. And if you look back on everything that had happened, my father leaves Japan, he's coming to the United States. He left Japan against my grandparents' wishes. So against his wishes, and now he's coming back to Japan with, you know, his only son to compete and represent, albeit a different country, but compete in the Olympics where my grandfather and my grandmother had actually lived near Nagano.

So it was this beautiful full circle for him. That was a culmination of like struggle, triumph, tribulation, and it contains all the emotional characters you can imagine. And he was showing up and he was saying, see, it was all worth it. It was all worth it. That was what he had in his head. So when I began skating, there was a clear path for him that I was, the end goal and result was going to be to compete at the Olympic games and, and make the family name proud.

I didn't really understand what that was like.

Ling Yah: I wonder if there was any hesitation about the sport in terms of just the physical side because I mean, you've said before, you know the sports that requires longer legs, shorter torso. So physically you were already sort of on the back foot compared to everyone.

And I think about that because when I was really young, I was part of the state synchronized swimmer team. And then you are really aware of your physical limitations, like the fact that, oh, you're not accessible, you're, you're just not grown the way that you normally would want if you wanna naturally thrive.

Mm-hmm. I wonder how important that part was in you just starting in that sport.

Apolo Ohno: Well, I didn't know the genetic disposition when I had first started in the sport. I didn't realize the advantage and disadvantage of the certain body types. I knew what it felt like to skate properly. So there's a certain feel that I would describe as like when you have the skate boot on and you can feel the blade underneath your foot and into contact with the ice, that feeling, which is very tactile, it felt natural to me.

I would sleep with my skates on at night when I was very young because I wanted to replicate this feeling of, I want these to feel just like socks. I want this to feel like I'm walking barefoot. I want this very awkward skating position that is speed skating to feel natural.

It was a weird sport to try to understand in all the biochems. So I, I think like body type wise didn't matter. Later on in my career I realized, wow, I actually have some disadvantages in terms of my body type. And there's other skaters around the world that I watch and I, my jaw drops.

I'm like, they skate so beautifully. If I could skate like that, I would never lose. Or if I had that body type, I would never lose if I had that technique, oh, it would be so much easier. The grass is always greener on the other side. That's the psychology. Yeah.

Ling Yah: Before we start talking about all this kind of titles that you want, I learned that when you told you thought about quitting and it was a traumatic experience, why was that?

How was your dad involved?

Apolo Ohno: Yeah, so when I was an inline skater and meaning like skating on roller skates and like inline blades, I joined a local roller skating club and there was a few competitions locally that and nationally my father wanted me, me to prepare for, but he couldn't and he didn't have the time to take me after school because he was still working.

Right? Single parent household father's always working, trying to provide for the family. And so what he would do is he would wake me up at like three 30 and four o'clock in the morning and take me to these, these locations, like these school parking lots and these empty church parking lots. He would turn the lights on in the car, the, the headlights for the car.

And then I had a minor's light strapped to my helmet, and he would just have me skate around. At the age of 12 years old, like, you just don't wanna be woken up in the middle of the night. Like that just feels like complete torture. And so one day I just told him, I was like, I wanna quit this sucks.

I don't want this anymore. I don't think this is planned by the way, but I think that what he did was he was, trying to get me to understand that sometimes in life, if we want to be great at something, it's going to demand doing those things that we deeply despise. Over and over again consistently, even though we deeply despise them.

And you have to embrace them. That's the stark reality is that, if you want to lose weight, you're not eating ice cream for breakfast, lunch, and dinner every single day. There is some levels of sacrifice and it's an emotional sacrifice. It is a feeling that you're going to have to come to terms with, and I didn't understand that.

But more importantly, I wanted to quit. I wanted to stop at all, and he didn't want that behavior to be ingrained in me. And so he made it very difficult for me to quit. And so what that did was it rooted this idea of fear, of failure. Deep, deep, deep within my psyche where I never felt like I could, I could walk away, I could quit, I could stop.

And it created this intense feeling of always wanting to prepare so that when I did show up, And I gave a hundred percent of my effort. It was not forgotten. I would be rewarded in some capacity and it was psychologically really difficult for me. You know, in going through the different arcs and storyline of my life.

I think that a part of this goes to when I was 14 years old, I was number one in the US I had beaten like people who were much older than me and I was like this prodigy at the time in speed skating in the sport. And then a year later, less than a year later, was the Olympic trials for the 98 Nagano Olympic Games.

And I finished dead last. And because I finished dead last, my father was obviously deeply disappointed because there goes the dream. The dad dream of bringing me back home was gone. He had tickets and everything. My grandparents had ticket and everything, and they actually went to the Olympics, believe it or not, even though I didn't make the tea.

Oh no, they can't waste those, right? And what he did was he took me after those Olympic trials to this like remote cabin we used to visit when I was younger, and it's the middle of winter. It's three and a half hour southwest of Seattle, Washington. It's right on the Pacific coast. It's right on the Pacific Coast.

And it's beautiful, but it's, it's very rough. It's not like a, Florida beach or something. It is literally like, it's raining hard, it's cold, it's very windy and it's dark. It's like, gets dark at like 4:00 PM every day, like 4:30 PM and he drops me off this place and he says, look, your behavior the past year has shown me that you have thrown away an incredible opportunity.

Not because you didn't make the team, but the way that you approached these Olympic trials and failed to recognize its importance because you could have made this team if you really dedicated yourself. And he dropped me off there. And I stayed in this cabin alone for like seven days or so, and I didn't have anything.

I didn't have a cell phone, I didn't have anything. I just was like living in the wild. And so that experience was traumatic. One, because I thought my dad hated me. Two, I felt like I was so lost and I was at the fork on the road in my life where I was trying to seek my own purpose and decision making process.

And three, I felt like I could have made that team, but I didn't. And so that fear of failure, I basically was a F before I had failed at making that team. So like I had self-sabotaged in a way because I was afraid of showing up to my best ability. And then being told, you're just not good enough. No one wants to be told that, right?

We all want like some internal, you know, reasoning. Why? Well, I didn't try as hard. Well, I was, you know, it's cause I don't really care about the outcome. Whatever that internal excuse is that you're trying to seek as valid is still an excuse no matter what. And that's what was happening with me. And so my father had recognized that behavior pattern and he had told me, I do not want this to be a part of your life.

I think this is a very dangerous path to go towards. While you cannot control every aspect of your life. What we can control is the preparation, the effort, the consistency, and the dedication towards whatever we're trying to achieve.

That's kind of basically what happened was my father put this on a platter and then he walked away and he said, tell me when you made a decision on what you wanna do with your life.

Call me when you're ready.

Ling Yah: Why did you decide you wanted to give this obscure sport a shot? I mean, you could have done anything, you were excelling in other sports as well. Why this one? Was it just to show that actually I could have made it to that game, so I'm just gonna make sure I make it to the next one.

Apolo Ohno: So I think it's a combination of, there was a belief that I could have made the team it was never about money. Cause I didn't even know what that meant back then, especially. But it also felt like there was unfinished business there, if that makes sense. It felt like, Had I given all of myself and not made the team, it probably would've been easier for me to walk away and say like, you know what?

maybe it's not for me. Maybe the the cards are not in my hand. But because I folded before I saw anybody else's cards right in the game of poker. I never give myself a chance. I quit before it was even readily available. I think my internal compass of truth knew that there was some unexplored territory that needed to be resolved.

I needed resolution. And the resolution came from , even at the age of 15 years old, believe it or not. Life is interesting. You never fully comprehend in the moment of why something's happening to you and why you feel the psychological pain that you are. And it sometimes you, Determined that you won't, I, I don't know if I can survive this. I don't know if this is for me you can survive it, right? It's about decision making. It's about removing the distractions, and it's about commitment. That's it. I mean, no outcome is guaranteed for you, you know, whatever that goal is.

I think that the likelihood of you reaching that success goes up with the amount of effort, time, dedication, and consistency that you put forth. That window gets bigger and bigger for you but it's not fully guaranteed. Anything can happen.

Basically my father was like, look, I'm gonna place you in this harsh environment because this kid's not listening to me.

I need this kid to understand the potential that he has within him, and whatever he wants to do, I'm going to support. Which is like very commendable for my father, right. To stop pushing me at that second and actually make me uh, the decision maker. And then my head basically said, okay, like, I am gonna do this one more time and I'm going to prove to myself that I can show up as my best self regardless of outcome.

And that was really powerful. I like relinquished this like weight vest that I had been carrying with me almost. And it was like, wow, this is actually freeing. And I was no longer handcuffed to the idea that this fear of failure that kept me back. I, I used it in a different way. I said, well, I'm still really afraid of failing.

I hate the way it feels, but I'm gonna use this as a motivation and a preparation tool, so I'm gonna use it to my advantage.

Ling Yah: How did you use it to your advantage compared to that period when you said before you were self-sabotaging yourself? What was the difference?

Apolo Ohno: So I think the self-sabotage still.

Was relevant in terms of like the self communication. So sports psychology 1 0 1 is be very mindful of what you say to yourself because you are always listening, okay? So the way that you communicate with yourself that no one else can hear, be very cognizant of what you are actually saying, because over time, your body in your mind will accept those things as truth.

That continued for up my entire career, but I became more mindful of what I was saying to myself. So the change was rooted in this idea that if I was able to use the fear of failure simply as a means of making sure that I stayed obsessed, committed and consistent, that was gonna be my superpower.

Because I feel like genetically there was better athletes out there, but this right here was the game changer. This. Was the single greatest tool that I felt had all the studies that I was doing from sports psychology, from watching my teammates, from seeing the other athletes. No one was training this, no one was using this in the way that I would read these like fairy tales of like monks training somewhere.

And maybe they're true. I, I don't know. But I wanted to believe those things. So the power of belief and faith in your own ability is immeasurable. Actually, it goes beyond sports science. And I learned a lot of that too from living in the wrestling community. The Olympic wrestlers, Greco, Roman, and freestyle and had seen these athletes.

they just were different humans. Like the idea of like sports science and creating like the perfect training program was like nonexistent to them. They were just like, we are just gonna train like warriors. And my mind is so strong that I will have the willpower to go through.

and I wanted to be a warrior. So a large part of this was I will do whatever it takes consistently because I'm so afraid of failing that I don't have the luxury because I'm not genetically designed as good as the next person for this sport. I don't have the luxury of sleeping in. I don't have the luxury of not wanting to go to the ice rink.

So what happened was to put it simply, I removed all of the negotiation out of my life around if I should do something, what I should do, and when I should go to the ice rink. For 15 years, those conversations didn't happen in my brain. I mean, except for like two weeks a year when I was setting my own training program and I was like, okay, what, what should I do?

Once the training program was set, it was get up A, B, C, D, go to the ice rink. That was it. That was routine. Very robotic, very consistent. And what I noticed looking back on my career was that every single time we created these frameworks and disciplines, my motivation no longer mattered. So people say like, that's incredible.

Like, how did you stay so motivated? I was like, it was never about motivation. It was about quieting the voice of defeat, of negativity, of toxicity, of you're not good enough. The only way to quiet that voice was to get up and go, get up and go every single day. And so everyone has this, by the way, everyone has their own internal stuff that they manage.

And I think the lesson for me is that that never goes away. The stuff, the challenges don't go away. How you interact with them and use them to, your advantages are solely within your own perception. That will become your reality. So the more that you can say, this is really. How do I tackle this? How do I accept it?

How do I accept myself? How do I move forward? How do I create a plan? And then you go upon that. That is the defining factor. And you have to be authentic with yourself. If you're negotiating and playing ping pong back and forth with like, yes, no, yes, no. What do I do? I'll go back. What kind of shoes should I wear when I go run?

What kind of outfit should I wear? Maybe I'll do it tomorrow. Maybe I'll do it later in the day. You've lost the game already. Just like remove all that stuff out. Create a really simple path. And that was my repeatable pattern of success for many, many years and many, many workouts. And then I began curating a psychological edge of leaning into the hardest workouts that we had.

And actually the hard of the workout, the more I would show up, the more I would lean in, the more I would smile, the more that I loved it. And it takes a little crazy to like love that type of physical pain every single day. But I'm telling you, your body and your mind adapt to it. It's remarkable what you can do when you do it consistently.

Ling Yah: What is specific steps that you did to ensure that you didn't falter on this path? Because every now and then you might be tempt. Were you ever tempted to just say, maybe I'll take a day off and that's when the hamster wheel starts and you just take two days, three days off? I learned that you never showed your medals as well as a way to motivate yourself.

Apolo Ohno: Yeah, we, I mean, I mean, we did have days off, so we had Saturday afternoon and Sunday fully off, so we have a day and a half every week full regeneration. We probably should have had more understanding the sports science today. And even on those days I would do like recovery jogs and I would go on the sauna and stretch and I would, you know, get deep tissue massage and all the recovery modalities you can imagine.

But looking back in the, in the world of sport, every workout seems to matter. Every hour of the day seems to matter. it's amazing it like really didn't. But I think it's something to do with the principle of thinking and the alignment of like, you believe these things really matter, therefore you take every minute of, every day, every hour as the level of importance skyrockets like tremendously.

So, you know, I mean, just look, I mean taking like the visibility of you know, how we approach the sport. There was no shortcut in any way. It was just this work that was done consistently, time and time again. I think something that's always misunderstood is that this life is like fun or it's like amazing and yes, like we love what we did and it's, it was great, but it's a very boring, mundane life.

Like we didn't do really much else. It's just what we did every single day. And it was that level of consistency that I fell in love with.

Ling Yah: You talked about the obsession part, but you also talked about as well being mindlessly handcuffed to it. Were you self aware at that time? Were you aware that, oh, I'm just doing this and there is also a darker side to it that you weren't fully aware of and you were explore later?

Apolo Ohno: I didn't know the power of the mind until I started working with a sports psychologist, so I'll just start there and say that when I was working effectively with a sports therapist mm-hmm. Someone to help me train my mind and be mindful of my, brain activity, I realized how toxic the conversation can be.

Mm-hmm. And how you can get warped into this like, flow state that is a negative state, not the flow state of optimal state, and you're so present in just thinking about the mistakes you just made. And it started in no other place, but the badminton court, believe it or not. So above the weight room in the Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs was the volleyball team would train up their massive building.

There was a volleyball team, basketball and in the corner there was the bab, the National Olympic Badminton team for the United States. and I used to watch these a I had never heard of Badman before. I'd watch these athletes play. And I was like, this is a crazy sport. Like, this is like a very athletic, I fell in love with the sport.

I, and I still love the sport, by the way, so I started playing badminton with my sports psychologist, like as warmup or after I had finished in the weight room as like another workout, like for fun. I just, this guy played tennis, like in college. So he was actually very good at racket sports, but I was just competitive.

I was like, I don't wanna lose this guy. Like, I really wanna beat this guy. And he started making these comments and he would say things like, Apollo, what happened that last point? And then I would make a few more mistakes. He's like, what's going through your head right now? I was like, and then my, and, and I was like, what's going through my head is I'm gonna throw this racket at you.

That's what's going through my head. And I didn't know what he was doing. He was, he was effectively trying to get me to listen and see the pattern of behavior. When I would start to lose, I would make more and more mistakes because I was dwelling on what just happened. Versus clearing the brain, clearing the mechanism as a new point and starting again.

That was the skillset. Huge failure. Clear the slate. Start again. Huge failure, clear the slate, recalibrate, try again, versus like, mistake, ah, boom. No mistake. Same mistake, same mistake, same mistake.

That's where it began for me was this internal conversation.

And so when I say the word, I was handcuffed to the obsessiveness.

I, I think that like, because I loved and cared about the sport so much, I felt like I didn't have the luxury of taking any time off, if that makes sense. Like everything mattered. Now, the handcuff part, Was dangerous because that voice was always saying like, there's someone on the other side of the world who's better than you, and you don't have the ability to rest like you need to do more.

So it made me extremely cerebral throughout my career. Now, this is not a necessarily a bad thing, but what I noticed today is that it removed me from the pure pleasure of being in an optimal state of skating. And so that took a lot of mental training and mindfulness and meditation and breathing techniques in order to calm that mind.

So, you know, one of your questions before was what are the actual strategies and tactics? Well, it's always been about clearing the frenetic energy that exists in your mind, right? Like these, these things here are the most incredible tools that we've had. Same with our laptops, right? I mean, the fact that we're doing this in different parts of the world is incredible.

But there's also this level of distraction that removes your ability to be completely in flow and in the zone and the frenetic energy. If you allow it to control you, you get nothing done. And if you do get something done, the quality is very low. So the greatest performance enhancement is learning to be totally in the flow state.

The Cal Newport calls it doing deep work, and a part of that is removing the things that are unnecessary and the obstacles and the removing the brick from the break, so to speak, and just allowing yourself to be in a flow state. So being in the mentality and using sports psychology, meditation and breath work was my mechanism.

It was my ability to slow down, observe, create internal conversation that was healthy. And then at the next stage was to say, how do I actually move forward? How do I create a state of awareness that is highly alert but very calm? That's how we make our best decisions. By the way, in speed skating, when I make the best pass, when I see something happen before it happens, that's all to do with how you process information through the orbitals into your mind and your surroundings.

Peripheral, all these things are like beautiful aspects of being human, right? And I think the way that we can use that today is in the same way you've got something very important that you care about learning to not disregard the sense of urgency, because urgency is good. It means that you care about the outcome, but not being so handcuffed to the outcome that it removes you from focusing in on the process.

That is the real challenge we face.

The people who do the best at any, any craft is they're fully enveloped in the process. And while the prize is great and they fully recognize and realize what the prize is, they're not thinking about the prize the whole time. They're thinking about being mechanically in the flow state, step one, step two, step three, step six, step 8, 16, 32, 64, et cetera.

I was just talking to my sports psychologist two days ago. The same person who taught me all these techniques. I mean, we were working together 23 years ago. We were working and we were telling stories and I was explaining to him about some of these challenges that I have and how I would like to retain what I had back then.

And he reminded me, he's like, don't forget the power of your mind. I was like, what do you mean? I don't have an Olympic race. He's like, oh, but you do. You absolutely have an Olympic race. It's just a long distance race. It's much different. It's not a 42nd race. So, my whole life post Olympics is all about dripping these pieces of belief and faith.

To get people to start listening to what they probably already really know is truth, that they have this incredible ability to continue whatever they're facing. And a lot of that comes down to this, this right here. Like, you know, your spirit, your heart, your mind, your body, your soul. And this can dictates so much of your reality.

So mechanically, it is the guiding principle for how I live my life today. And it was back then, it was my greatest asset that you can possibly imagine was the breath work. Basically focusing in on lowering my heart rate, breathing in through my nostrils, out through my mouth, being in a calm state and exhaling, exhaling this negativity, this like disbelief this, this insecurity, this self-doubt and breathing in this feeling of like self-acceptance.

This is what I do today, by the way. You know, strength, fortification, unification, possibility, all these things. I promise you that you can alter the direction of your life and the speed at which you move. And it sounds counterintuitive because you're slowing things down. But the key here is that just like the race that I skated in the Olympics, which is 40 seconds long, it doesn't feel like 40 seconds.

To me, they felt like five minutes long. I felt like Neo from the Matrix, right? Like everything seems much more controllable, everything is slower, and that's everything to do with this. Like you're rehearsing this over and over again and the effort between trying way too hard and it's really difficult and you don't go very fast between, it's almost like you don't, you're not even really trying, but you're going, it's this, that, that, that line is minuscule between trying too hard and not trying hard enough being on just being trying hard just enough is this beautiful flow state that when I watch athletes who get that, that it looks beautiful and effortless.

And we've seen that in many sports. And that's why I love sports so much because it is the most incredible display of what that looks like. But you can have that in conversation. You can have that with dancing, you can have that with art, with creative, you can have that in business. You can have that when you're reading.

You can have that when you're having a meal. I mean, there's, there's thousands of different possibilities there. It's about finding that flow state. Sorry, I went on the ramble there. No, that's

Ling Yah: fantastic. There were so many points to bring out. You talked about flow state. When was the last time you found yourself in the flow state?

That wasn't in sports context.

Apolo Ohno: The last time that I was in a flow state was Yeah, I had gone for a run and I got lost on this run. I was in a new city. I got lost in this. I was in Orlando and I got lost and I didn't bring my phone with me. I had no idea where I was. And I intended to go out for like a 40 minute jog and it was like an, it was like an hour, 50 minutes at this point.

I mean, I was way in a different area. And then when I got back, so like that's not, I mean, I was in the flow state, that's why I got so lost by the way. Cause I wasn't paying attention. But when I got back I had prepared, I was doing some corporate speaking stuff, so I remember I went on stage and something about that episode of running allowed me to tap back into this like flow.

And I didn't have my phone with me, so, It was quite easy for me to kinda get in that state, and I just gave this presentation around kind of psychological awareness, changing human behavior, understanding routines and habits, and kind of fortifying a layer of belief around it all. And it was, it, that, that was the la that's where I get similar aspects of being in flow state outside of sport and movement and activity is, it typically comes to when I'm speaking to people.

The other time it's typically when I'm doing some activity in nature, there's like something about, even if it's just walking outside where I can kind of get into this repetitive pattern where I'm just, I'm just observing what's going on. Like these thoughts that are coming through my mind.

And then I'm actually tonight a friend of mine is hosting a sound bath at his place. which is fascinating because Sound Bath to me is all about being in flow state. Mm-hmm. You have to be highly tuned in, you know, listening. You have to be calm. It's quiet. So there's something about those aspects.

Noise level, quiet heart rate, and then the, the voices in your head start to slow down. Start to, and this is why people, whenever we talk about meditation or mindfulness or just breath work, people say, that's not for me. I'm like, Hey, I get it. It's okay. But find something that is for you. Find something to slow that pace down and you can ramp it back up.

Right. If you're someone who's like always needs to go and you love coffee or tea, whatever, like I do too, I think going through the waves, just like sport is really important to have the downward cycle so that you can go back up again. I just know that. You make the best decisions that way.

I said that before, but also you're the most clear-headed when you're not making that frenetic energy being a part of your controlling life. And the only way to do that, I believe, is quieting the mind. it's been a lifesaver for me post Olympic sport. It really, really has.

Ling Yah: Hey everyone, just a gentle reminder that STIMY episodes like this one are now open to sponsorships, and this is one of the spots that you can get. To be honest, STIMY is not gonna accept everyone because we want to make sure that your mission aligns with the interest of the STIMY community.

So yes, dear listeners, I'm putting you first, but if you're interested, please do drop an email at [email protected], and let's start chatting. All right, now let's get back to this episode

Why you say makes me think so much of what Andrew Huberman says a lot, he's a Stanford professor, if you've heard of him. Of course. He always talks about the power of introspection. That sounds very much as though that's necessary to get into the flow state. Do you sort of, I suppose, schedule that into your daily life to ensure you always have that space?

Apolo Ohno: I do. I'm not a hundred percent accurate with doing it every single day, but it's pretty beautiful the difference when I am doing it versus when I'm not. It's very clear that I should be doing this every single day. introspection. And I'm looking at, I have notes all around my desk here that are all about introspection.

In order to make the best decisions moving forward, one needs to create space to reflect upon those decisions. If you don't give yourself the space, then you're not giving your mind the time to comprehend the possibilities of alternate outcomes, of creative expression, of importance.

All these, you know, of risk, all these things. So giving space is really important. And if you don't have space, make the space.

If you're just always being controlled by something that is an exterior motive here or an exterior force You can't create that space like you need to be able to see clearly in order to create that space.

So I just go back to like the sport, Huberman is great. he obviously gets it on so many levels. And he brings this great blend of like science and creativity to how he articulates every message. And I, I do think there's something there about creating this, even for just like three to five minutes every day.

That's all you need to create. And it's just simple. Do it consistently. You know, for me, I've talked about like, what were the things that went well today intentionally, what did I expect today to go, did I accomplish my goals today? Why not? What were some things that I've learned about myself today that I can work on for tomorrow?

And then what actually went right today? And if nothing went right, you still have to write something down. You have to find something. And what that's doing. For me is it's training your brain to find the silver lining, right? This is, this is important. This is an exercise, this is not an end result.

This is an exercise to prompt you to consistently train your mind, to seek for something that's underneath the contextual layer that we normally dig in. We only see the surface usually, but this is an exercise to create more depth of kind of mindset. And that happens to introspection.

Ling Yah: We need to go back to your career cuz I wanted to talk about the Great divorce as well.

You had a tremendous run. I wonder, there was one part that stood up for me was at the Salt Lake City Olympics and it was fairly controversial. I wonder if you could just share a bit about that period for those who are unaware of what happened.

Apolo Ohno: The Salt Lake City Olympics was my first Olympic Games. Yeah. That was a favorite going into those Olympics. It was six and a half months post nine 11. So this was like a pretty devastating time for many people. But they were very afraid of having and hosting Olympic games on home soil on the US grounds because they felt that it was unsafe.

There was this level of uncertainty and chaos that still existed in the air. And the Olympic Games is a big feat to accomplish. I had walked into those Olympic games thinking it was all about me. I didn't realize the power of we mm-hmm. In that kind of teamwork environment.

And my first race, I had been the favorite. My first final was the thousand meters, and I was in the lead with a quarter of a lap remaining, and then someone had fallen into the left side of me, which caused me to fall down. And the skater behind me and the skater behind him, So like four people had fallen down in the last quarter lap of this race.

I scrambled to my feet and I threw my skates across the finish line only to realize that I received the silver medal, which I was deeply confused because the person who won gold was this Australian skater who was a lap behind, behind. I remember getting off of the ice and being like, really just trying to comprehend what just happened.

It was like scary. It was, I didn't understand. It felt like, it felt like someone had ripped something out of my heart. Sort of felt like, cause it felt like it. I winning the gold felt mine and it was like, Hey, like someone, someone cheated me out of this. I had like, cut my leg in the process of falling because of the impact of hitting the pads.

So like, you know, my legs out like this. And then my right leg went in and just like basically stabbed my left leg with the end of my blade. I ripped my racing suit down. I didn't know. There was this huge gash on my left leg and I called the medic to come in. And so in walks in, comes running in one of the medics and he looks at me and he is like, that was the craziest race I'd ever seen in my life.

That was incredible. How did you get back up? I was like, oh my God. Like, I've been thinking about this whole time. why me? Woe is me. When people were celebrating that, I got back up and then I saw my father and he looks at me and he was like, I, I got stitched up and I had ice around my leg. And he looks at me.

He's like, that was just so incredible. Like, you did so good. So, you know, I gave you some background and context around growing up in a single parent household. My father pushing me. You can probably realize by now that the only thing I really was seeking was like my, my father's affirmation of being enough.

That's really what this came down to be. And I got that and he gave me that affirmation. Like, that was incredible. You did so good. And so I went and received the, the, the silver medal, and I celebrated as if it was the gold. Someone had asked me, what does it feel like to have lost the gold medal? And I said, I didn't, I didn't lose the gold medal.

I won the silver. And it was a pivotal moment in my career, both in terms of like recognizability in the United States, but also people were cheering and screaming because I didn't complain. I took the race as it is. It's a part of life. in short track speed skating, we say something, we say that's short track.

Unexpected things happen when you feel like you're the favorite and you don't win. Sometimes that short track, whether it's fair or not, doesn't matter. Unfortunately, it doesn't say that on the results sheet 20 years from now, there's no asterisk next to your name that explains the story. It's just a result.

And you can't change it. So you have to either accept it and move on, or you can live in this stewed soup of bitterness for the rest of your life. That is Apollo's decision. I obviously didn't choose that, so it was a crazy time. Highly competitive, and it felt like I was able to, you know, like tell my story and the American public fell in love with that story.

It was really cool.

Ling Yah: How did the Turin Olympics feel for you then? A chance of redemption? So.

Apolo Ohno: So four years later going into my next Olympic games you know, I was highly competitive with many athletes particularly the South Korean team. And I had not had the competition in the Olympics like I had originally intended.

I was like injured. I had not performed very well. And in the very last race on the very last day, the 500 meters in which I was not a favorite to Mein, I ended up winning gold in that race. So there was a lot of redemptive aspects of that. And it was like personally a much more visceral experience because my team had basically accepted that I probably was not going to win gold this Olympic games.

And I hated that. I was like, how dare anyone give up on me? Like, we still have another race. I know that it's not my best race, but there's a 1% chance I could win. Isn't that enough? Isn't that enough? And it did happen, right? It was, it was, the cards fell in my favor, so that was amazing. And then a year later I found myself on this reality show called Dancing With the Stars, which is like really crazy.

And then I ended up winning that show and then I decided not to go down the path of like becoming like an, I don't know, like going down the path of Hollywood instead continuing on my path for one more Olympic games. And Yeah, my last Olympic games was in Vancouver 2010.

Ling Yah: How did you decide to turn away from Hollywood?

Because you probably will have been thinking about your long-term career. So Hollywood would've promised a far longer career than the sports.

Apolo Ohno: Yes. Yeah, yeah. And it was, I mean, look, Hollywood at the time was, it was like the sexy answer, right? It was like this, like, you know, I mean, and Hollywood is a crazy place.

It really is. Like nothing makes sense, but then everything also makes sense. It was an opportunity. I mean, the doors that were opened for me during that time were, they are no longer available, just to let you know. Like, it was amazing. And I didn't fully comprehend what that meant. I just knew that I was like, I'm still young.

Like I want to go back and continue to skate. I don't, I don't, this Hollywood stuff is fun, but I don't know if it's really for me. So sometimes being naive is actually, pretty strong as an asset. And ignorance is bliss. Absolutely. Like I just didn't even know, you know, that this was never gonna come my way again.

But I learned how to speed skate in Vancouver, BC I grew up in Seattle, which is like three hours south, two and a half hours south Vancouver, bc and the final Olympic games were being held in Vancouver seat for my final Olympic games. I was like, this seems like this says all the green lights I could imagine.

And I was like, I'm gonna do this one more, one more time. And it's gonna require a tremendous amount of reinvention and changing of my skating technique, style mentality, and perfection towards a sport. Because I was getting older and people had already recognized my behavior patterns on the ice. So my strategy was very well understood from every athlete.

My skating style was studied for thousands and thousands of hours by many, many people all coast of the world. So I needed to come up as a new version of myself. And that was, that was challenging.

Ling Yah: Were you very clear going in that that would be your last Olympics, and did that change the way you prepped

Apolo Ohno: it did.

I was cleared two years, three years out from the Olympic Games. I had told myself, this is the last one, my father told me, he says, A lion is at its most dangerous when it knows it's near the end. yeah, by the way, that's like how my dad talks to me. You know, like these types of like weird, like philosophical, yeah.

Like these, like weird riddles and stuff.

So the, the goal had changed. The goal had changed in my final Olympic games from win gold. Win gold, win gold to you will leave no stones unturned in your preparation so that when you arrive into Vancouver, you will have no regrets.

You will have zero regrets about what had just happened, and you will no longer have that weight vest of uncertainty if you're able to do that. And I knew I correlated, there's a very high probability of me making the podium and winning medals in every distance if I could do the work. I mean, we had changed the entire way that we had thought about the sport.

The way that we trained. I ate the same things every single day within five minutes of each other. Like it was just on point on time. Food was fuel. Not an almond more, not an almond less. There was mental prep every night. There was no balance. This was hardcore, ultra intense, high volume training.

And it was extremely obsessive and it was about reinventing my body type, my strength, everything. And it was a crazy time. It required me to retool the way that I thought about the sport, how we articulated what recovery would look like, how we thought that I would skate lap times three to five years in advance for, you know, when I started this process, three to four years in advance when I started.

And it was hard how to reverse engineer that process. But it was beautiful. it was a beautiful aspect. it felt like nothing on the, nothing else in the world existed or mattered. Right. And then looking back, that was like the height of the financial crisis. I didn't even know what that meant.

I mean, I used to watch, you know, C N B C and Bloomberg, right? To see what's going on. Like, oh, Brookshire Hathaway stock is really down. But I didn't feel it. I didn't, it just like I lived in this bubble. But that is the power. Of being able to remove yourself from other things that are happening. And we know people that are like that.

Some people are just like, they don't know what's going on in the world. They're not paying attention at all, right? They're just doing their thing and they're giving themself space to focus on what they're doing. I mean, look, I'm probably much more informed today than I was before, but I'm probably way more distracted at the same time.

So I've got this general knowledge base about things. But again, bringing it back to the center was a big part of that. So what I can tell you going into those final Olympic games, what I learned about myself was that your body and your mind can take on so much more than you realize. It is unbelievable.

The level of physical conditioning that we had gone through. The level of consistency of training was almost psychotic.

The level of intensity that it brought to every training of every session for years was just at a level that other people were just unwilling to accept was possible.

And the reason why we were told no in terms of the goals that I had set, and I'd asked, well, I wanna be this body weight and be this strong. I said, well, that's not, that's impossible. But in my head I was like, but no one is actually put in the work that I'm about to put in. So how can you say that?

Your equation is off. You think we only have three years, but the way that I train, I'm actually training for six, right? It's actually double because of the way that I dedicate myself towards those things. Hence the deep work, cue to Cal Newport and being in that flow state. So.

Ling Yah: Do you miss that level of psychotic obsession? Have you applied that since you left the sports world?

Apolo Ohno: I do, and I don't, I miss it in sport. I don't miss that level of. Be. So, the downside of psychotic obsession being 40 today is that it alienates everything else out for my life.

And to me, that's not worth it anymore. To me, life is more than just about the goal that I have in front of me. It's more about balance. And so I seek to have deeper human connection. I wanna see other people succeed. When I was performing as an athlete, I didn't wanna see anybody else succeed except for me.

I have changed as the person over the past 13 years, and it's taken a lot of deep work in order to want to show up with more empathy, to seek self-improvement, to understand where my microtraumas come from so I can work on them, so that I can show up as the best version of Apollo so I can help other people find their own true north.

Like that's my purpose today.

Do I miss that in sport? Yes. Because there's something beautiful about that. And I think that I can take bits and pieces from that framework. And apply it in what we call the gas principle in sport, which is, you know, and you step on the gas and you let off the gas, you step on the gas's.

Now it comes in cycles and it comes in rhythms. But learning to remove yourself from those environments, the detachment phase is very, very critical. it's really important and it keeps my mind more healthy.

Ling Yah: You did consider coming out of retirement and you spoke to Michael Phelps about it.

How do you arrive for that decision not to?

Apolo Ohno: Well, when you get in these environments where you watch your friends and your peers compete and you see them older than most other people say that they should be competing at, and you started thinking yourself maybe I can do this one more time. I think the question is not, if you could do it one more time, the question is, is this the right decision for you Apolo, and do you actually want to do this, Apolo?

I made sure to not make a decision when I was at the 2012 London Olympic Games when I was with him and watching those games and broadcasting those games, I made sure not to make the decision there because I obviously had a lot of confirmation bias. Everyone was gonna say, absolutely, we want you to compete again, because they wanna see me on the ice again, right?

So I took time off, I went to the cabin and my dad dropped me off at when I was 15, and I said like, man, like is this it? Do I, should I do this? the answer was no.

You seek an alternative path and that's gonna be hard. And a part of you growing up or growing is going against the grain.

I know sport, I know the Olympic path. It's so familiar to me. But true growth comes from doing something that is unfamiliar and it does not come natural to you.

Ling Yah: So how has the great divorce been? What was that period like? Because as I told you earlier, I'm going through something like that as well.

So this, yeah. Interview can come at a more opportune time for myself.

Apolo Ohno: Look, I think the Great Divorce, which is a chapter in my book, hard Pivot. We talk about this thing that you fall in love with that gives you the positive affirmation, tells you that this is your purpose. You're given the head nods of approval from your peers, your people, your paycheck.

This is why you're here. This is what you're good at. Don't worry about anything else. This is what you, this is the path that you chose. And then if you snap your fingers, either by choice or by force, and you're now doing something entirely different, that is when the great divorce occurs. Because the.

Title of the name tag that you once had as your email signature or whatever it might be, will actually or could be entirely different. And it's not who you are, it's what you did, right? It's the attributes that made you successful at that title, but that title is not you. It's a part of you. So just like Apolo was an Olympic athlete, it's not who I am at the core in its entirety, but it's a large part of me.

So going through that process was really hard, and it lasted many years longer than I could have ever possibly imagined. And I'll be honest with you, I have this conversation with, I had a conversation this morning with a very dear friend of mine. I said, Hey, like, do you think that we have several times of our life where we seek the question and answer of what is my purpose?

And does that change? I think the answer is yes. I think that your purpose may change many times throughout your life, and that's totally okay. It's got to do with short-term objectives and goals, medium-term and then long-term, and then making sure that those things that you're pursuing are in alignment.

They are congruent with the person that you desire to be and that you believe that you can be. How you show up in this world for what reasoning is entirely up to you. The short-term goals may distract away from that at times as long as it's related to the long-term one. That took me a long time to realize when it came to the reinvention stage, so I had to go explore.

The curiosity was there. The understanding, the hunger to win outside of the world of sport was very much relevant, so that meant I needed to allow myself to learn from as many people as possible. Win, lose, fail, draw, doesn't matter. It's all about experiences and then not allowing the fear state. To override and keep you in a state that is in inaction.

You want to be in a form where you are always ready to press the button if you go or don't go. And you want to be in control of that. So I think fear is powerful if it keeps you prepared and it keeps you honest in your commitment. It is a negative if you allow it to override your ability to create action in your life.

And you can do this, right, the like. Like people can create frameworks and say, oh, there's my mind again. It's coming in trying to make me feel safe because it wants me to go back to the old thing, the 1.0 version of myself, But I know the 1.0 version of myself is always gonna be there. And going to the 2.0 version is hard because it's unfamiliar.

I'm starting from scratch. I don't know anyone. It's like I'm taking on a new language. Nothing seems like it makes sense. But the equation of consistency plus hard work plus volume equals high percentage outcome likelihood of having success. So increase the probability that that's what it comes down to.

And I didn't know that then, but what I realized, what this was gonna take a lot of work. It was not easy. It's not easy and it's never easy.

Ling Yah: What is your advice in terms of just exploring to see what's out there? Because I find that, at least for me personally, finding and discovering there are lots of opportunities, but there's also that driven fear of, but if I don't say yes now, it might never come back again.

Yeah. But if I say yes and I commit, then I might. That means that I don't have the opp, there's space to do all these other things. So how did you manage that?

Apolo Ohno: Well, when I first started my path of reinvention, I said yes to everything. Mm-hmm. I mean, I'm just gonna be honest. I'm just Yes to everything. I traveled all over the world.

I mean, I've been to 80 plus countries, so many different businesses and they were all learning lessons. I would say now I say yes to far less things. So I've created an area where this is what I want to do. These are the things that are associated with what I want to do. And if it's not in those categories, then I'm just not gonna do them.

Which gives me more space to concentrate, more effort towards the things that I set out to do in the beginning. So if someone is going through this reinvention stage and process, the thing that I can recommend is surround yourself with people to give you perspective on what those other things are.

Like. Ask them what is life like as, you know, whatever you're doing. How did you get into it?

Do you feel like you're good at your job? Do you like what you do? We learn by communication and conversation. So I always suggest people to find peer groups and just communicate with people.

Talk to other humans, and you will hear patterns of behavior that will make sense to you. And they may actually also affirm the path that you've already chosen, but it's gonna take doing some work. So if you're someone who's an introvert and you don't like talking to people, well then do some reading, right?

Go that path first. But I do think there's a lot that we can learn, and you can do this on forums, you can do this through social, I mean, there's many, there's no excuse, Seek the answers consistently. Use technology as a tool to help you get connected with people that have lived lives in many different aspects.

So I'll give you an example. I'm fascinated with the American healthcare industry. It's a huge. It's obviously been very beneficial for some peop for many people, but it's also fragmented and it's broken and it's sluggish and it's archaic and it's harsh and it's difficult. I'm not in that business.

I wanna learn about it because I just like to learn about things. So create learning as a superpower for you, not you, I mean, saying like, in general, like this is, you have control over these things and I always suggest people to be open to interpretation.

Ling Yah: You said before, start surrounding yourself as the right people.

You have your life board of directors or starting five. How did you decide on those five? How did you find them?

Apolo Ohno: Well, I think the personal board of directors, just to reignite the conversation, if you were gonna think about yourself as a business, you know, you would have between two and five personal board of directors.

People who have and care about your best interests, people who are incentivized to see you win, and they're going to give you the cold, hard, transparent truth and opinion about your behavior and which direction you should go in in your life. You need these people not only for their support, but also because you believe and you trust them.

We all need that. And sometimes just one person, maybe it's two people, but we need that. So think of yourself as a business because you are a business, even if you work for a company, you absolutely are. And so who are the trusted advisors that you can surround yourself with? Really, really critically important.

For me, it goes back to the history that I have with those people, what they've seen me go through, how they've seen me grow. They know my tendencies, my pitfalls, my weaknesses, and they know my strengths. And so they help keep me when I get a little bit wobbly, they keep me straight on the right path.

Ling Yah: You say you can write entire manifest on the life lessons I've given you.

What are some of the life lessons that you don't mind sharing?

Apolo Ohno: Oh man. I mean, there's just so many. My father gives me a lot of of life lessons, right? Like, which leads me to want to read more. Like I, I love reading poetry. I love reading. I love reading things that are inspirational about life and that are a little bit more harsh. So, Douglas Malach is an American writer and author and he writes these poems.

One of the poems is called Good Timber, and I really, I hope people can read these. If you're going through a harsh time in your life, which if you haven't, you will, don't worry. Unfortunately, life is just harsh at times.

It's catered towards. But just like read into this as if it's talking to everyone.

And it talks a lot about, good timber does not grow with ease. The stronger wind, the stronger trees, the greater sky, the greater length, right? So like talks about these things about nurturing a tree. So like the callous is on my hands that I have here are from lifting weights. They are to protect my hand over long durations of time.

From lifting weights up your mind and your spirit becomes calloused over time. Heartbreak relationships, loss of family members and loved ones failing at life, finances, all kinds of stuff. The way we look at ourselves in the mirror, right? Everything. But that poem to me is really powerful. So, Going back, like I love reading.

There's thousands of like historical context around whether it's, you know, deep in China, whether it's Japanese, whether it's Greek, whether it's, philosoph in nature, whether it's like modern in some tech entrepreneur, there seems to be a similarity around life can be beautiful, it's going to be harsh, but it's a part of growing.

And just like the callous, just like the wind, just like the greater sky, the body is tree. Our mind is a tree. Our heart, we grow, we can expand. And so whatever traumas you've been through have fortified you into the person you've become today. And it's going to make you stronger even if you don't see it today that way.

Ling Yah: You have spoken earlier about figuring out who you are, and you also went to war for five weeks with business executives, and that was precisely the question they wanted you to ask each other. Who are you? So how would you answer that question?

Apolo Ohno: So can I give context about the question? Of course.

Yes. So I think this was like two and a half weeks into this program. I'm with like 25, 30 executives from all over the world, and we all had, we, we all live in the dorms together the whole time. And we're in class for like 12 hours a day. We spend every, we have breakfast, lunch, and dinner together, drinks later after, and we're working on other projects and it's, it's like a very highly immersive protocol.

And so we did this one exercise with the, here you are, three rounds of, I think it's two minutes each. And if you and I were doing this right now, Linga, we would do, I would ask you who you are and you could gimme an answer. I would keep asking you. I can only ask you one question. That is Who are you?

Who are you? Who are you? And you can respond with as many different iterations or whatever that you want. In the beginning, the first round, everyone mentioned their title, what they do at work, the things that describe them in terms of like the job description, et cetera. Then it kind of maybe got into the family.

The second time they skipped over the job stuff. They went more into the family stuff, more into where they live, more into a little bit what they like. The third stuff went much deeper, the third round, I mean, and that's when I felt, I felt like in six minutes I got to know these executives more than I did for the past two and a half weeks.